Clofazimine: Uses

Leprosy

Clofazimine is used in rifampin-based multiple-drug regimens for the treatment of multibacillary and paucibacillary leprosy. The drug also has been used in the treatment and prevention of erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) reactions (lepra type 2 reactions) in leprosy patients. The World Health Organization (WHO) and most clinicians currently recommend that rifampin-based multiple-drug regimens be used for the treatment of all forms of leprosy.

Multiple-drug regimens may reduce infectiousness of the patient more rapidly as well as delay or prevent the emergence of resistant organisms. Rifampin-based multiple-drug regimens are necessary because of the increasing incidence of dapsone-resistant Mycobacterium leprae, and these regimens are designed to be effective against all strains of M. leprae, regardless of their susceptibility to dapsone. Because rifampin is bactericidal against M. leprae, once-monthly administration of rifampin is the principal component of the currently recommended multiple-drug regimens; clofazimine and dapsone are included in the regimens to prevent the emergence of rifampin-resistant M. leprae.

Some adverse effects (e.g., skin discoloration) reported with clofazimine may cause a substantial compliance problem in certain patients or populations receiving the drug as part of recommended antileprosy regimens.

Often, appropriate counseling about clofazimine (e.g., advantages of its use, reversibility of skin discoloration) are sufficient to encourage the patient to continue taking the drug.

Multibacillary Leprosy

For the treatment of multibacillary leprosy (i.e., more than 5 lesions or skin smear positive for acid-fast bacteria), the WHO currently recommends a 12-month multiple-drug regimen that includes rifampin, clofazimine, and dapsone. The clofazimine dosage regimen recommended by WHO for use in the treatment of multibacillary leprosy includes both a daily dose and a once-monthly dose of the drug; the once-monthly dose is included to ensure that optimal concentrations of clofazimine are maintained in body tissue, even if the patient occasionally misses a daily dose of the drug. If a patient with multibacillary leprosy will not accept or cannot tolerate clofazimine, the WHO recommends an alternative regimen that includes ofloxacin and minocycline.

Paucibacillary Leprosy

For the treatment of paucibacillary leprosy (2-5 lesions), the WHO recommends a 6-month regimen of rifampin and dapsone. If a patient receiving this regimen experiences severe adverse effects related to dapsone, the WHO recommends that dapsone be discontinued and clofazimine substituted.

Leprosy Reactional States

Erythema Nodosum Leprosum

Clofazimine has been used for the treatment and prevention of erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) reactions (lepra type 2 reactions) in leprosy patients. The fact that clofazimine has anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects, as well as antimycobacterial effects, apparently contributes to the drug’s beneficial effects in the treatment of ENL reactions. However, clofazimine is not as effective or as rapidly acting as other agents used in the treatment of ENL (e.g., corticosteroids, thalidomide), and should not be initiated as the sole agent for the treatment of severe ENL. Some clinicians suggest that thalidomide may be the drug of choice for the treatment of moderate to severe ENL reactions, especially severe, recurrent reactions; however, the risks versus benefits of thalidomide therapy must be considered, especially in women of childbearing potential.

ENL is a recurrent immunologically mediated syndrome that occurs principally in patients with multibacillary leprosy. While ENL reactions have been reported to occur in 10-50% of lepromatous leprosy patients and 25-30% of borderline lepromatous patients, these reactions are being reported less frequently in patients receiving the currently recommended multidrug antileprosy regimens that include clofazimine than in those who received dapsone monotherapy.

ENL usually occurs after initiation of anti-infective therapy for leprosy (generally within the first 2 years of treatment), although occasionally it may occur spontaneously in untreated lepromatous leprosy patients or after treatment is discontinued. These reactions are considered to be a manifestation of the disease rather than an adverse reaction to antileprosy regimens.

Clinical symptoms include cutaneous papules or nodules that are painful or tender, erythematous, and histologically vasculitic; the papules may pustulate and ulcerate, appear as recurrent crops, and are widely distributed, generally appearing on extensor surfaces of the extremities and on the face.

Cutaneous symptoms of ENL may be accompanied by peripheral neuritis (usually of the ulnar nerve), fever, malaise, wasting, uveitis, lymphadenitis, orchitis, and glomerulonephritis. Histologically, ENL is an acute vasculitis or panniculitis that is thought to be secondary to immune (i.e., antigen-antibody) complex deposition.

Depending on the severity of manifestations, ENL reactions generally are treated using analgesics, corticosteroids, and/or thalidomide. While mild ENL reactions in some patients may be adequately managed with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent (e.g., aspirin, indomethacin) and bed rest, moderate to severe ENL reactions generally are treated with corticosteroids and/or thalidomide and hospitalization may be required. The antileprosy regimen usually is continued while the ENL reaction is treated.

Corticosteroid therapy (usually prednisolone) generally is effective for the treatment of moderate and severe ENL and usually is necessary when ENL is complicated by neuritis; however, long-term therapy may be required, and there is a risk that ENL patients (especially those with chronic ENL) may become steroid dependent. If prolonged corticosteroid therapy becomes necessary, initiation of clofazimine therapy (if the drug is not already included in the regimen) or a temporary increase in clofazimine dosage (in patients already receiving clofazimine as part of a multidrug antileprosy regimen) may allow a reduction in corticosteroid requirements.

Clofazimine dosage effective for the treatment of ENL reactions is slightly higher than that usually recommended for the treatment of leprosy. Early diagnosis and treatment of ENL is important since these reactions are associated with considerable morbidity, especially if chronic, recurrent ENL occurs. Therapy for leprosy and leprosy reactional states should be undertaken in consultation with an expert in the treatment of leprosy.

Other Leprosy Reactional States

Clofazimine also has been used for the treatment of reversal (type 1) reactions in patients with borderline or tuberculoid leprosy. However, use of clofazimine in type 1 reactions is controversial since efficacy of the drug for these reactions has not been fully evaluated. In some patients with type 1 reactions, use of clofazimine appeared to aggravate the reactional state. Reversal reactions presumably occur because the patient is able to mount an enhanced delayed hypersensitivity response to the residual leprosy infection and this leads to swelling of existing skin and nerve lesions.

Existing lesions become erythematous and edematous and may ulcerate; fever and an increased leukocyte count frequently occur, and acute neuritis and loss of nerve function may develop. Corticosteroid therapy (usually prednisolone) is the treatment of choice for type 1 reactions; analgesics and surgical decompression of swollen nerve trunks may also be used.

Clofazimine has not been shown to be effective in the treatment of other leprosy-associated inflammatory reactions (e.g., Lucio’s phenomenon, downgrading reactions). In the US, the Gillis W. Long Hansen’s Disease Center at 800-642-2477 should be contacted for further information on the treatment of leprosy and management of leprosy reactional states.

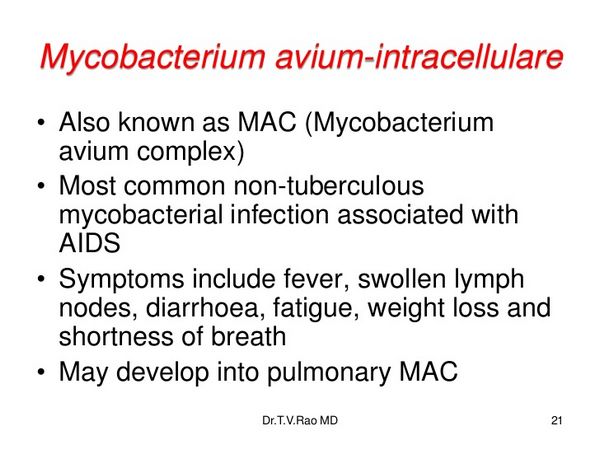

Treatment of Mycobacterium avium Complex (MAC) Infections

Pulmonary and Localized Extrapulmonary MAC Infections

Clofazimine has been used in multiple-drug regimens in the treatment of pulmonary and localized extrapulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infections. However, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and some clinicians currently recommend that such infections be treated with a macrolide-containing regimen that includes a minimum of 3 drugs (i.e., clarithromycin or azithromycin, rifabutin or rifampin, and ethambutol). (See Treatment of Pulmonary and Localized Extrapulmonary MAC Infections, under Management of Other Mycobacterial Disease: Mycobacterium avium Complex (MAC) Infections, in the Antituberculosis Agents General Statement 8:16.04.)

The ATS states that while there are no controlled trials comparing regimens with or without a macrolide for the treatment of pulmonary MAC infections, most experts consider non-macrolide-containing regimens to be inferior. In patients whose disease has failed to respond to a macrolide-containing regimen or who are intolerant of such a regimen, the ATS suggests that a regimen including ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice daily) or ofloxacin (400 mg twice daily), clofazimine (100 mg daily), ethionamide (250 mg twice daily, increased to 3 times daily as tolerated), and prolonged use of streptomycin or amikacin (3-5 times weekly) may be associated with at least short-term conversion of sputum to negative; however, the ATS states that the long-term success of such a “salvage” regimen is unknown but likely very low.

Disseminated MAC Infections

Disseminated MAC infections characteristically occur in patients with advanced HIV infection who have absolute helper/inducer (CD4+, T4+) T-cell counts less than 100/mm3. Limited data from retrospective and prospective analyses indicate that disseminated MAC infection is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with AIDS and that treatment of the infection may increase survival.

However, death occurs rapidly following diagnosis of disseminated MAC infection, underscoring the importance of early diagnosis and of antimycobacterial prophylaxis for this infection.

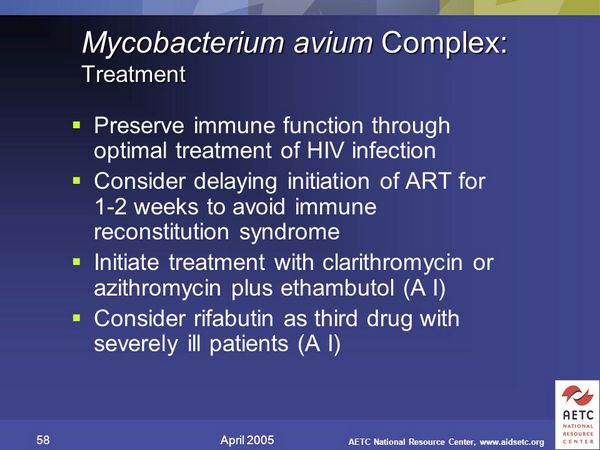

A clearly superior regimen for the treatment of disseminated MAC infection in patients with AIDS has not been established to date. However, currently available data suggest that multiple-drug regimens containing a macrolide (i.e., clarithromycin, azithromycin) are superior to non-macrolide-containing regimens and that inclusion of clofazimine in macrolide-containing regimens does not add to their efficacy (i.e., in terms of preventing clarithromycin resistance) and may even be associated with reduced survival. Therefore, the Prevention of Opportunistic Infections Working Group of the US Public Health Service and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (USPHS/IDSA) currently states that clofazimine should not be used for the treatment or prevention of recurrence of disseminated MAC infection.

In a randomized, comparative study in adults with HIV infection and MAC bacteremia who had CD4+ T-cell counts less than 100/mm3, treatment success (defined as the patient being alive, having either no fever or a reduction of 1°C or more in initial body temperature, and having negative blood cultures for M. avium) was similar at 2 and 6 months in patients receiving a 3-drug regimen consisting of clarithromycin (1 g twice daily for 8 weeks, then 500 mg twice daily), rifabutin (450 mg daily), and ethambutol (1. g daily) or a 2-drug regimen consisting of clarithromycin (1 g twice daily for 8 weeks, then 500 mg twice daily) and clofazimine (200 mg daily for 8 weeks, then 100 mg daily) for at least 28 weeks; however, the 3-drug regimen was associated with fewer relapses of MAC bacteremia and a decrease in the emergence of clarithromycin-resistant MAC strains.

Results of another randomized, comparative study in patients with AIDS and MAC bacteremia demonstrated improved functional status, decreased weight loss, and increased survival in patients receiving a 3-drug, clarithromycin-containing regimen compared with a 4-drug, clofazimine-containing regimen that did not include a macrolide antibiotic.

In this study, MAC bacteremia was cleared in 69% of evaluable patients receiving clarithromycin (1 g twice daily), ethambutol (approximately 15 mg/kg daily), and rifabutin (300 or 600 mg daily) compared with 29% of those receiving rifampin (600 mg daily), ethambutol (approximately 15 mg/kg daily), clofazimine (100 mg daily), and ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice daily). Median survival was 6.6 months with the clarithromycin-containing regimen versus 5.2 months for the 4-drug regimen.

Among patients treated for at least 4 weeks, MAC bacteremia resolved more frequently with the 3-drug regimen. The ATS recommends therapy that includes either clarithromycin or azithromycin in conjunction with ethambutol and rifabutin for the treatment of disseminated MAC infection in HIV-infected patients. The choice of the drug regimen should be made in consultation with an expert, and treatment may need to be continued for the duration of the patient’s life.

Other Mycobacterial Infections

Although clofazimine is active in vitro against M. tuberculosis, efficacy of the drug in the treatment of tuberculosis has not been determined and clofazimine is not included in current recommendations for the treatment of the disease.

Clofazimine reportedly was effective in the treatment of lupus vulgaris in one patient, although M. tuberculosis was not isolated from the cutaneous lesions in this patient prior to initiation of therapy.

Clofazimine is active in vitro against M. ulcerans, and the drug reportedly has been used with some success in a limited number of patients as an adjunct to surgery for the treatment of Buruli skin ulcers caused by the organism. However, in some studies, clofazimine generally was ineffective when used in the treatment of cutaneous lesions caused by M. ulcerans, and surgical excision is the treatment of choice for M. ulcerans infections.

Other Uses

Clofazimine has been used with some success in the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum either alone or in conjunction with corticosteroid therapy. Although not all cases of pyoderma gangrenosum have responded to clofazimine therapy, the drug has been effective in some cases that failed to respond to corticosteroids or dapsone therapy. Clofazimine also has been used with some success in a limited number of patients for the treatment of several other inflammatory or pustular dermatoses, including generalized pustular psoriasis, acne vulgaris, Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis), and granuloma faciale.

There are conflicting reports on the efficacy of clofazimine in the treatment of lupus erythematosus. Although the drug appeared to be effective in the treatment of skin lesions in a few patients with annular or discoid lupus erythematosus resistant to conventional antimalarial or corticosteroid therapy, clofazimine was ineffective in other patients with chronic discoid lupus erythematosus or diffuse, photosensitive, systemic lupus erythematosus lesions.

Clofazimine has been used with some success in a limited number of patients for the treatment of Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, Miescher’s granulomatous cheilitis, and Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. A

lthough slight perifollicular pigmentation reportedly occurred in a few patients with vitiligo who received clofazimine, this may have been the result of deposition of the drug in skin tissue rather than stimulation of melanogenesis since the drug generally had no beneficial effect on vitiligo in other patients.