Drug Nomenclature

International Nonproprietary Names (INNs) in main languages (French, Latin, Russian, and Spanish):

Note. The name Isopyrin, which has been applied to isoniazid, has also been applied to ramifenazone.

Pharmacopoeias

In China, Europe, internationally, Japan, the US, and Vietnam.

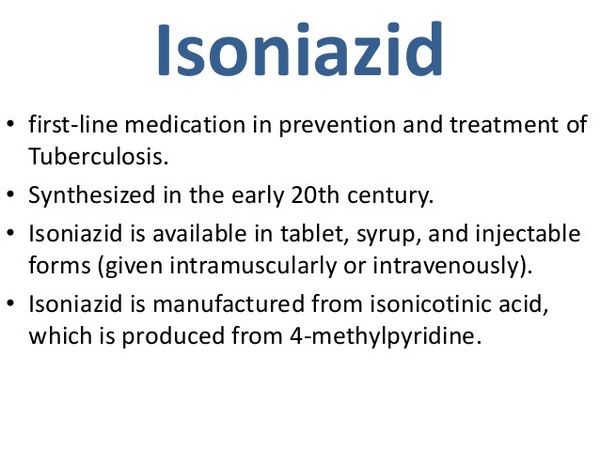

European Pharmacopoeia, 6th ed., 2008 and Supplements 6.1 and 6.2 (Isoniazid). A white or almost white crystalline powder or colorless crystals. Freely soluble in water; sparingly soluble in alcohol. A 5% solution in water has a pH of 6.0 to 8.0.

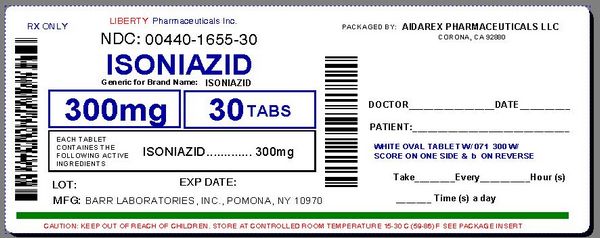

The United States Pharmacopeia 31, 2008 (Isoniazid). Colourless, or white, odorless crystals, or white crystalline powder. Soluble 1 in 8 of water and 1 in 50 of alcohol; slightly soluble in chloroform; very slightly soluble in ether. PH of 10% solution in water is between 6.0 and 7.5. Store in airtight containers at a temperature of 25°, excursions permitted between 15° and 30°. Protect from light.

Pharmacokinetics

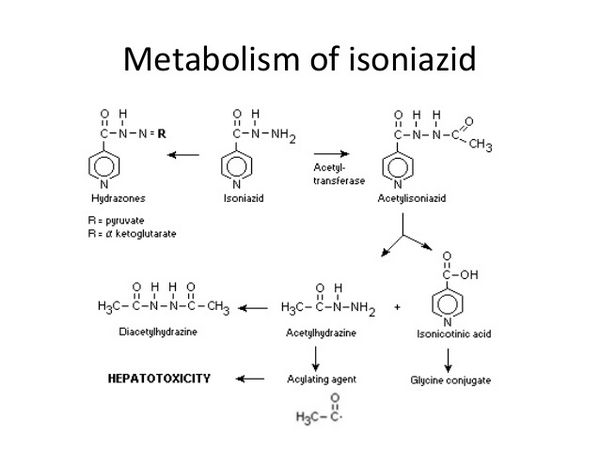

Isoniazid is readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and after intramuscular injection. Peak concentrations of about 3 to 7 micrograms/mL appear in blood 1 to 2 hours after an oral fasting dose of 300 mg. The rate and extent of absorption of isoniazid is reduced by food. Isoniazid is not considered to be bound appreciably to plasma proteins and is distributed into all body tissues and fluids, including the CSF. It appears in fetal blood if given during pregnancy, and is distributed into breast milk. The plasma half-life for isoniazid ranges from about 1 to 6 hours, with shorter half-lives in fast acetylators. The primary metabolic route is the acetylation of isoniazid to acetyl isoniazid by N-acetyltransferase found in the liver and small intestine. Acetylisoniazid is then hydrolyzed to isonicotinic acid and monomethylhydrazine; isonicotinic acid is conjugated with glycine to isonicotinic glycine (isonicotinic acid), and monomethylhydrazine is further acetylated to dimethylhydrazine. Some unmetabolized isoniazid is conjugated to hydrazones. The metabolites of isoniazid have no tuberculostatic activity and, apart from possibly monoacetylhydrazine, they are also less toxic. The rate of acetylation of isoniazid and monoacetylhydrazine is genetically determined and there is a bimodal distribution of persons who acetylate them either slowly or rapidly. Ethnic groups differ in the proportions of these genetic phenotypes. When isoniazid is given daily or 2 or 3 times weekly, clinical effectiveness is not influenced by acetylator status. In patients with normal renal function, over 75% of a dose appears in the urine in 24 hours, mainly as metabolites. Small amounts of drugs are also excreted in the feces. Isoniazid is removed by hemodialysis.

Distribution

Therapeutic concentrations of isoniazid have been detected in CSF and synovial fluid several hours after an oral dose. Diffusion into saliva is good, and it has been suggested that salivary concentrations could be used in place of serum concentrations in pharmacokinetic studies.

HIV-infected Patients

Malabsorption of isoniazid and other antituberculous drugs may occur in patients with HIV infection and tuberculosis and may contribute to acquired drug resistance and reduced efficacy of tuberculosis treatment. For further information on the absorption of antituberculous drugs in HIV-infected patients.

Pregnancy

Isoniazid crosses the placenta, and average fetal concentrations of 61.5 and 72.8% of maternal serum or plasma concentration have been reported. The half-life of isoniazid may be prolonged in neonates.

Uses

Active Tuberculosis

Isoniazid is used in conjunction with other antituberculosis agents in the treatment of clinical tuberculosis.

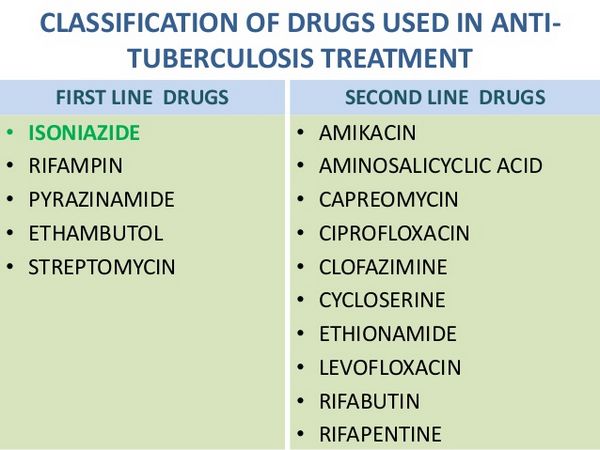

The American Thoracic Society (ATS), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) currently recommend several possible multiple-drug regimens for the treatment of culture-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. These regimens have a minimum duration of 6 months (26 weeks) and consist of an initial intensive phase (2 months) and a continuation phase (usually either 4 or 7 months). Isoniazid is considered a first-line antituberculosis agent for the treatment of all forms of tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis known or presumed to be susceptible to the drug.

Isoniazid is commercially available in the US alone or in fixed combination with rifampin (Rifamate®) or in fixed combination with rifampin and pyrazinamide (Rifater®). The fixed-combination preparation containing rifampin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide (Rifater®) is designated an orphan drug by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the treatment of tuberculosis. Although oral isoniazid is preferred for the treatment of tuberculosis, the drug may be given IM for initial or retreatment of the disease when the drug cannot be given orally.

Latent Tuberculosis Infection

Isoniazid usually is used alone for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection to prevent the development of clinical tuberculosis. Previously, “preventive therapy” or “chemoprophylaxis” was used to describe a simple drug regimen (e.g., isoniazid monotherapy) used to prevent the development of active tuberculosis disease in individuals known or likely to be infected with M. tuberculosis. However, since the use of such a regimen rarely results in true primary prevention (i.e., prevention of infection in individuals exposed to infectious tuberculosis), the ATS and CDC currently state that “treatment of latent tuberculosis infection” rather than “preventive therapy” more accurately describes the intended intervention and potentially will result in greater understanding and more widespread implementation of this tuberculosis control strategy.

Individuals at risk for developing tuberculosis include those who have been recently infected with M. tuberculosis and those who have clinical conditions that increase the risk of latent tuberculosis infection progressing to active disease. The likelihood that a positive tuberculin test represents a true infection with M. tuberculosis is influenced by the prevalence of infection in the population being tested. The ATS and CDC state that since the general population of the US has an estimated M. tuberculosis infection rate of 5-10% and the annual incidence of new tuberculosis infection without known exposure is estimated to be 0.01-0.1%, the tuberculin skin test has a low positive predictive value in individuals without a known or likely exposure to M. tuberculosis. To prioritize the use of resources for identifying those at risk for developing tuberculosis and minimize the incidence of false-positive tuberculin test results, the ATS and CDC currently recommend that tuberculin testing be targeted toward groups at high risk and discouraged in those at low risk. The ATS and CDC currently define positive (i.e., significant) tuberculin reactions (i.e., reactions highly likely to indicate true infection with M. tuberculosis) in terms of 3 cut-off points (i.e., levels of induration) based on the sensitivity, specificity, and prevalence of tuberculosis in different groups: 5 mm or more of induration for individuals at highest risk for developing clinical tuberculosis, 10 mm or more of induration for those with an increased probability of infection or with clinical conditions predisposing to enhanced progression of infection to active tuberculosis, and 15 mm or more of induration for individuals at low risk in whom tuberculin testing generally is not indicated.

Key Groups for Tuberculin Testing and Treatment

- Individuals with HIV Infection

- Those with an induration reaction of 5 mm or greater should receive LTBI therapy unless contraindicated.

- Preventive therapy is recommended even for negative tuberculin tests if there is known exposure to active tuberculosis.

- Isoniazid therapy may be beneficial for tuberculin-negative children born to HIV-infected mothers.

- Close Contacts of Tuberculosis Patients

- Contacts with a significant reaction (≥5 mm) should be treated for LTBI, regardless of age.

- Children under 5 years should be treated regardless of test results due to higher disease susceptibility.

- Immunocompromised Individuals

- Those receiving prolonged corticosteroid therapy or organ transplants should be treated if they have a significant tuberculin reaction.

- Immunosuppressed individuals who are contacts of active tuberculosis cases should also receive treatment.

- Individuals with a Prior Tuberculosis History

- Those with healed but untreated tuberculosis should receive LTBI therapy, regardless of age.

- High-Risk Population Groups

- Recent immigrants from high-prevalence countries, residents in long-term care facilities, and healthcare personnel exposed to tuberculosis patients should be considered for treatment if they show significant tuberculin reactions.

- Children and Adolescents

- Infants and children exposed to high-risk adults should be treated if they have a significant tuberculin reaction.

Testing and Treatment Considerations

- Routine testing is not recommended for low-risk populations, but treatment may be considered for those with significant reactions.

- Prior to starting isoniazid therapy, patients must be screened for active tuberculosis and liver conditions, ensuring no contraindications exist.

This streamlined approach ensures that vulnerable populations receive appropriate screening and treatment to prevent the progression of latent tuberculosis into active disease.

Isoniazid Monotherapy

Isoniazid monotherapy is recommended for treating latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) in both HIV-infected and HIV-negative adults, with a preferred regimen of 9 months taken daily or twice weekly. For infants and children, a similar 9-month regimen is advised, although some experts suggest extending treatment to 12 months for HIV-infected children. While the 9-month regimen is optimal, a 6-month regimen can be used for HIV-negative adults, offering substantial protection and potentially lower costs. However, it is not recommended for children or those with prior tuberculosis evidence. Research indicates that regimens shorter than 6 months are ineffective, and a large study confirmed that a 6-month course is more effective than shorter options. The ATS and CDC emphasize the importance of compliance, recommending at least 270 doses for the 9-month regimen and 180 doses for the 6-month option. Intermittent dosing should be directly observed to ensure adherence. If treatment is interrupted for over two months, a medical evaluation is necessary before resuming therapy.

Alternative Regimens

While isoniazid monotherapy generally is the regimen of choice for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection, a 4-month regimen of daily rifampin monotherapy can be used as an alternative regimen in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, especially when isoniazid cannot be used because of resistance or intolerance.

Limited data suggest that a short-course (e.g., 2-month) regimen consisting of rifampin and pyrazinamide given daily is effective in treating latent tuberculosis infection in HIV-infected patients, and the ATS and CDC state that the efficacy of this regimen is not expected to differ in HIV-negative patients. However, hepatotoxicity (including some fatalities) has been reported in patients receiving rifampin and pyrazinamide regimens for the treatment of latent tuberculosis and, although multiple-drug regimens containing rifampin and pyrazinamide are still recommended for the treatment of active tuberculosis, the ATS, CDC, and IDSA now state that regimens containing both rifampin and pyrazinamide generally should not be offered for the treatment of latent tuberculosis in either HIV-infected or HIV-negative individuals.

HIV-infected Individuals

Factors to consider in selecting the appropriate regimen for treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV-infected individuals include the likelihood that the infecting organism is susceptible to isoniazid (isoniazid is the preferred agent for isoniazid-susceptible M. tuberculosis), the potential for drug interactions with rifampin in patients receiving HIV protease inhibitors or NNRTIs, and the possibility of severe liver injury with pyrazinamide-containing regimens. The choice of therapy requires consultation with public health authorities if the infecting organism is resistant to isoniazid and rifampin.

Recommendations for treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV-infected adults generally are similar to those for HIV-negative adults; however, the 6-month isoniazid monotherapy regimen usually is not recommended and use of rifabutin monotherapy may be necessary instead of rifampin monotherapy if there are concerns about drug interactions with antiretroviral agents the patient may be receiving. The ATS and CDC recommend that HIV-infected adults and adolescents with latent M. tuberculosis infection receive a 9-month regimen of isoniazid given daily or twice weekly; a 4-month regimen of rifampin or rifabutin given daily; or a 2 to 3-month regimen of rifampin and pyrazinamide given daily (this regimen no longer recommended in most patients).

For HIV-infected infants and children, recommended regimens for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection are a 9- to 12-month regimen of isoniazid given daily or twice weekly or a 4- to 6-month regimen of rifampin given daily.

Pregnant Women

For pregnant women who are at risk for progression of latent tuberculosis infection to active disease, particularly those who have HIV infection or have been infected recently, the ATS and CDC state that the initiation or discontinuance of therapy for latent tuberculosis infection should not be delayed on the basis of pregnancy alone, even during the first trimester. For women whose risk of active disease is lower, some experts recommend delaying treatment until after delivery. Patients with HIV infection or radiographic evidence of prior tuberculosis should receive 9 rather than 6 months of isoniazid therapy. The ATS and CDC state that some experts would use rifampin and pyrazinamide as an alternative regimen for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV-infected pregnant women, although pyrazinamide should be avoided during the first trimester. The ATS and CDC state that a regimen of isoniazid administered daily or twice weekly for 9 or 6 months is recommended in these pregnant women who do not have HIV infection.

Drug-Resistant Latent Tuberculosis Infection

In individuals likely to be infected with M. tuberculosis organisms that are resistant to both isoniazid and rifampin and are at high risk for developing tuberculosis, the ATS and CDC recommend regimens consisting of pyrazinamide and ethambutol or pyrazinamide and a quinolone anti-infective (e.g., levofloxacin or ofloxacin) for 6-12 months if the organisms from the index case are known to be susceptible to these drugs. Immunocompetent contacts may be managed by observation alone or be treated with such regimens for 6 months; immunosuppressed individuals, including those with HIV infection, should be treated for 12 months. Clinicians should review the drug-susceptibility pattern of the M. tuberculosis strain isolated from the infecting source-patient before selecting a regimen for treating potentially multidrug-resistant tuberculosis infections. In individuals likely to have been infected with M. tuberculosis organisms that are resistant to both isoniazid and rifampin, the choice of drugs used for the treatment of latent infection requires expert consultation. Prior to initiation of therapy for latent tuberculosis infection in patients with suspected multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, careful assessment to rule out active disease is necessary.

The AAP states that until susceptibility test results are available, contacts who are likely to have been infected by an index case with isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis should receive both rifampin and isoniazid. If the index case is proven to be excreting organisms that are completely resistant to isoniazid, isoniazid should be discontinued, and rifampin should be given for at least six months. The AAP recommends consulting an expert when making decisions about therapy for latent tuberculosis infection in children with isoniazid and/or rifampin-resistant M. tuberculosis.

Administration

Isoniazid usually is administered orally. The drug may be given by IM injection when oral therapy is not possible. The fixed-combination preparation containing isoniazid and rifampin (Rifamate®) and the fixed-combination preparation containing isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide (Rifater®) should be given either 1 hour before or 2 hours after a meal; the manufacturer states that Rifater® should be given with a full glass of water.

Solutions of isoniazid should be sterilized by autoclaving.

Dosage

Oral and IM dosages of isoniazid are identical.

Active Tuberculosis

In the treatment of clinical tuberculosis, isoniazid should not be given alone. The drug is considered a first-line agent for the treatment of all forms of tuberculosis. Therapy for tuberculosis should be continued long enough to prevent relapse. The minimum duration of treatment currently recommended for patients with culture-positive pulmonary tuberculosis is 6 months (26 weeks), and recommended regimens consist of an initial intensive phase (2 months) and a continuation phase (usually either 4 or 7 months). However, the American Thoracic Society (ATS), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) state that completion of treatment is determined more accurately by the total number of doses and should not be based solely on the duration of therapy. For information on general principles of antituberculosis therapy and recommendations regarding specific multiple-drug regimens and duration of therapy.

Adult Dosage

The ATS, CDC, and IDSA recommend that adults and children 15 years of age or older receive an isoniazid dosage of 5 mg/kg (up to 300 mg) once daily when isoniazid is used in conjunction with other antituberculosis agents.

When an intermittent multiple-drug regimen is used to treat tuberculosis, the ATS, CDC, and IDSA recommend that adults and children 15 years of age or older receive isoniazid at a dosage of 15 mg/kg (up to 900 mg) once, twice, or three times weekly.

Pediatric Dosage

Infants and children tolerate larger doses of isoniazid than adults and may be given isoniazid in a dosage of up to 10-20 mg/kg once daily, depending on the severity of the disease. The maximum dosage of isoniazid recommended by the manufacturers for children is 300-500 mg daily. The ATS, CDC, IDSA, and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend that when isoniazid is used in daily multiple-drug regimens in pediatric patients, an isoniazid dosage of 10-15 mg/kg (up to 300 mg) daily should be used. The AAP cautions that the use of an isoniazid dosage exceeding 10 mg/kg daily in conjunction with rifampin may increase the incidence of hepatotoxicity.

When an intermittent multiple-drug regimen is used for the treatment of tuberculosis in pediatric patients, the ATS, CDC, IDSA, and AAP recommend an isoniazid dosage of 20-30 mg/kg (up to 900 mg) twice weekly.

Fixed-Combination Preparations

When isoniazid is administered as the fixed combination containing isoniazid and rifampin (Rifamate®) as part of a multiple-drug regimen for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis, the usual adult dosage of Rifamate® is 2 capsules (600 mg of rifampin and 300 mg of isoniazid) once daily.

Although the fixed-combination preparation was formulated for daily regimens, the ATS, CDC, and IDSA state that Rifamate® can be used in twice-weekly regimens provided additional isoniazid is administered concomitantly.

When used in an intermittent multiple-drug regimen, these experts state that two capsules of Rifamate® (600 mg of rifampin and 300 mg of isoniazid) and an additional 600 mg of isoniazid (900 mg of isoniazid total) may be given twice weekly using directly observed therapy (DOT).

The manufacturer states that Rifamate® should not be used for the initial treatment of tuberculosis but only after the efficacy of the rifampin and isoniazid dosages contained in the fixed-combination preparation has been established by titrating the individual components in the patient.

When isoniazid is administered as the fixed combination containing isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide (Rifater®) in the initial phase (e.g., initial 2 months) of multiple-drug therapy for pulmonary tuberculosis, the manufacturer states that the adult dosage of Rifater® given as a single daily dose is 4 tablets (480 mg of rifampin, 200 mg of isoniazid, 1.2 g of pyrazinamide) in patients weighing 44 kg or less, 5 tablets (600 mg of rifampin, 250 mg of isoniazid, and 1.5 g of pyrazinamide) in those weighing 45-54 kg, and 6 tablets (720 mg of rifampin, 300 mg of isoniazid, 1.8 g of pyrazinamide) in patients weighing 55 kg or more. In individuals weighing more than 90 kg, additional pyrazinamide may need to be given in conjunction with the fixed-combination preparation to obtain an adequate dosage of this drug. T

The ratio of rifampin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide in Rifater® may not be appropriate in children or adolescents under the age of 15 because of the higher mg/kg doses of isoniazid usually given in children compared with those given in adults.

Latent Tuberculosis Infection

Isoniazid is usually the sole antituberculosis drug for a minimum of six months to treat latent tuberculosis infection. Every effort should be made to assure compliance for at least six months since preventive therapy of shorter duration appears to provide little benefit. If drug administration cannot be directly observed, spot testing of urine for isoniazid metabolites has been recommended to assess compliance.

The ATS and CDC currently recommend a 9-month daily isoniazid regimen or, alternatively, a 9-month twice-weekly isoniazid regimen for adults regardless of HIV infection status. Continuing isoniazid therapy for latent tuberculosis infection for longer than 12 months provides no additional benefit. It is also recommended that isoniazid therapy for latent tuberculosis infection be continued for 9-12 months in HIV-infected infants and children.

The ATS and CDC state that completion of therapy for latent tuberculosis infection is determined more accurately by the total number of doses and should not be based solely on the duration of therapy. The 9-month daily isoniazid regimen should consist of at least 270 doses administered within 12 months (allowing for interruptions in the usual 9-month regimen), and the 6-month daily isoniazid regimen should consist of at least 180 doses given within 9 months. Isoniazid regimens in which the drug is given twice weekly should consist of at least 76 doses administered within 12 months (for the 9-month regimen) or at least 52 doses within 9 months (for the 6-month regimen).

Important Safety Information

Liver function tests should be performed periodically in patients receiving isoniazid. In addition, patients should be questioned monthly for signs and symptoms of liver disease and should be instructed to report to their physician any of the prodromal symptoms of hepatitis (e.g., persistent fatigue, weakness or fever exceeding 3 days, malaise, nausea, vomiting, unexplained anorexia). If these symptoms appear or if signs suggestive of hepatic damage occur, isoniazid should be discontinued promptly, since continued use of the drug in these patients has been reported to cause a more severe form of liver damage.

Some clinicians recommend discontinuing isoniazid therapy if serum aminotransferase concentrations are more than 3-5 times higher than the upper limit of the normal range or if patients develop manifestations of hepatitis. Patients who have had signs or symptoms of hepatic damage during isoniazid therapy generally should receive alternative antituberculosis agents, but if isoniazid must be reinstituted, the drug should be restarted only after hepatic symptoms and laboratory abnormalities have cleared. Isoniazid should be restarted in very small and gradually increasing dosages and should be discontinued immediately if there is any indication of recurrent liver involvement.

The AAP states that the incidence of hepatitis during isoniazid therapy in children is rare and that routine determination of serum aminotransferase concentrations is not recommended. However, liver function tests should be monitored approximately monthly during the first several months of treatment in children with severe tuberculosis, especially meningitis and disseminated disease.

The AAP states that monitoring of liver function tests should also be performed in patients with concurrent or recent liver disease, those receiving a high daily dose of isoniazid (more than 10 mg/kg daily) in combination with rifampin and/or pyrazinamide, those who are pregnant or within 6 weeks postpartum, those with clinical evidence of hepatotoxicity, and those with hepatobiliary tract disease from other causes, and those receiving other hepatotoxic drugs concomitantly (especially anticonvulsants). In most other patients, monthly clinical evaluations for 3 months, followed by evaluation every 1-3 months to observe for manifestations of hepatitis or other adverse effects of drug therapy, is appropriate.

Isoniazid should be used with caution in daily users of alcohol, individuals who inject illicit drugs, patients with chronic liver disease or severe renal impairment, and those with a history of prior therapy in whom isoniazid was discontinued because of adverse effects (e.g., headache, dizziness, nausea) possibly, but not definitely, related to the drug. Minor dosage adjustments may be necessary in patients with severe renal impairment. Limited data based on a retrospective analysis of isoniazid-associated hepatitis deaths suggest that the risk of fatal hepatitis associated with the drug may be increased in women, particularly black and Hispanic women, and during the postpartum period.

Periodic ophthalmologic examinations should be performed in patients who develop visual symptoms while receiving the drug. The manufacturers recommend that ophthalmologic examinations (including ophthalmoscopy) be performed prior to initiating isoniazid therapy and periodically during therapy, even without the occurrence of visual symptoms; however, some clinicians question the necessity of this precaution.

Isoniazid should be used with caution in patients who are malnourished or predisposed to neuropathy (e.g., diabetics, alcoholics), and pyridoxine generally should be administered concomitantly. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends concomitant pyridoxine therapy in children and adolescents who have an abnormally low milk and meat intake, in those with nutritional deficiencies (including all symptomatic HIV-infected children), in breast-feeding infants and their mothers, and in pregnant women.

Isoniazid is contraindicated in patients with acute liver disease or a history of previous isoniazid-associated hepatic injury. Although preventive therapy should be deferred in these patients, the ATS and CDC state that seropositivity for hepatitis B surface antigen is not a contraindication for such therapy. Isoniazid is also contraindicated in patients with a history of severe adverse reactions to the drug, including severe hypersensitivity reactions or drug fever, chills, and arthritis.

Carcinogenicity

Isoniazid has been reported to induce pulmonary tumors in animals; however, there is no evidence to date to support carcinogenic effects in humans.

Concern about the carcinogenicity of isoniazid arose in the 1970s when an increased risk of bladder cancer in patients treated with it was reported. However, no evidence to support a carcinogenic effect of isoniazid was found in more than 25,000 patients followed up for 9 to 14 years in studies organised by the USA Public Health Service and in 3842 patients followed up for 16 to 24 years in the UK.

Pregnancy and Lactation

No isoniazid-related congenital abnormalities have been observed in mammalian reproductive studies; however, it has been reported that isoniazid may exert an embryocidal effect when administered orally to pregnant rats and rabbits.

Although the safe use of the drugs during pregnancy has not been definitely established, isoniazid (combined with rifampin and/or ethambutol) has been used to treat clinical tuberculosis in pregnant women. The American Thoracic Society (ATS), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) state that isoniazid is considered safe for use in pregnant women, but the risk of hepatitis may be increased in the peripartum period.

The manufacturers state that the potential benefits of isoniazid therapy for latent tuberculosis infection during pregnancy should be weighed against the possible risks to the fetus. The use of antituberculosis agents for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in pregnant women is controversial.

Some experts prefer to delay treatment until after delivery because pregnancy itself does not increase the risk for progression to disease, and 2 studies suggest that there may be an increased risk of hepatotoxicity during pregnancy and the early postpartum period. However, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and other experts state that pregnant women who have positive tuberculin skin tests without evidence of clinical tuberculosis should receive therapy with isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection if they are likely to have been infected recently or have high-risk medical conditions, especially human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The AAP recommends that such therapy begin after the first trimester.

If isoniazid is administered during pregnancy, concomitant administration of pyridoxine (25 mg daily) is recommended.

Because isoniazid crosses the placenta and is distributed into milk, neonates and breast-fed infants of isoniazid-treated mothers should be carefully observed for evidence of adverse effects.

Porphyria

Isoniazid is considered to be unsafe in patients with porphyria, although there is conflicting experimental evidence of porphyrinogenicity.

Interactions

The risk of hepatotoxicity may be increased in patients receiving isoniazid with a rifamycin or other potentially hepatotoxic drugs, including alcohol. Isoniazid can inhibit the hepatic metabolism of a number of drugs, in some cases leading to increased toxicity. These include the antiepileptics carbamazepine, ethosuximide, primidone, and phenytoin, the benzodiazepines diazepam and triazolam, chlorzoxazone, theophylline, and disulfiram. The metabolism of enflurane (see Effects on the Kidneys) may be increased in patients receiving isoniazid, resulting in potentially nephrotoxic levels of fluoride. Isoniazid has been associated with increased concentrations and enhanced effects or toxicity of clofazimine, cycloserine, and warfarin. For interactions affecting isoniazid, see below.

Alcohol

The metabolism of isoniazid may be increased in chronic alcoholics, and this may lead to reduced isoniazid effectiveness. These patients may also be at increased risk of developing isoniazid-induced peripheral neuropathies and hepatic damage.

Antacids

Oral absorption of isoniazid is reduced by aluminum-containing antacids; isoniazid should be given at least 1 hour before the antacid.

Antifungals

Serum concentrations of isoniazid were below the limits of detection in a patient also receiving rifampicin and ketoconazole For the effect of isoniazid on ketoconazole.

Antivirals

The clearance of isoniazid was approximately doubled when zalcitabine was given to 12 HIV-positive patients. In addition, care is needed since stavudine and zalcitabine may also cause peripheral neuropathy; the use of isoniazid with stavudine has been reported to increase its incidence.

Corticosteroids

Giving prednisolone 20 mg to 13 slow acetylators and 13 fast acetylators receiving isoniazid 10 mg/kg reduced plasma concentrations of isoniazid by 25 and 40%, respectively. Renal clearance of isoniazid was also enhanced in both acetylator phenotypes, and the rate of acetylation increased in slow acetylators only. The clinical significance of this effect is not established.

Food

Palpitations, headache, conjunctival irritation, severe flushing, tachycardia, tachypnoea, and sweating have been reported in patients taking isoniazid after ingesting cheese, red wine, and some fish. Tyramine or histamine accumulation has been proposed as the cause of these food-related reactions, which could be mistaken for anaphylaxis.

It has been recommended that sugars such as glucose, fructose, and sucrose not be used in isoniazid syrup preparations because the formation of a condensation product impairs the drug’s absorption. Sorbitol may be a suitable substitute if necessary.

Antimicrobial Action

Isoniazid is highly active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and may have activity against some strains of other mycobacteria, including M. kansasii. Although it is rapidly bactericidal against actively dividing M. tuberculosis, it is considered to be only bacteriostatic against semi-dormant organisms and has less sterilizing activity than rifampicin or pyrazinamide. Resistance of M. tuberculosis to isoniazid develops rapidly if it is used alone in the treatment of clinical infection, and may be due in some strains to loss of the gene for catalase production. Resistance is delayed or prevented by the combination of isoniazid with other antimycobacterial, which appears to be highly effective in preventing the emergence of resistance to other antituberculous drugs. Resistance does not appear to be a problem when isoniazid is used alone in prophylaxis, probably because the bacillary load is low.

Mycobacterium Avium Complex

Synergistic activity of isoniazid plus streptomycin and, to a lesser degree, isoniazid plus clofazimine, against Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo.

Antituberculosis Agents

There is some evidence that the adverse nervous system effects of isoniazid, cycloserine, and ethionamide may be additive; therefore, isoniazid should be used with caution in patients receiving cycloserine or ethionamide. Aminosalicylic acid appears to reduce the rate of acetylation of isoniazid; the effect is usually not clinically important. Isoniazid inhibits the multiplication of BCG; therefore, the BCG vaccine may not be effective if administered during therapy with the drug.

Carbamazepine

Initiation of isoniazid therapy (200 or 300 mg daily) in patients receiving carbamazepine has resulted in increased serum concentrations of the anticonvulsant and symptoms of carbamazepine toxicity, including ataxia, headache, vomiting, blurred vision, drowsiness, and confusion. These symptoms of carbamazepine toxicity subsided either when carbamazepine dosage was decreased or when the antituberculosis agent was discontinued.

This interaction presumably occurs because isoniazid inhibits the hepatic metabolism of carbamazepine. In at least one patient, concomitant use of carbamazepine and isoniazid also appeared to increase the risk of isoniazid-induced hepatotoxicity, apparently because the anticonvulsant promoted the metabolism of isoniazid to its hepatotoxic metabolites. If carbamazepine and isoniazid are administered concomitantly, serum concentrations of the anticonvulsant should be closely monitored, and the patient should be observed for evidence of carbamazepine toxicity; carbamazepine dosage should be decreased if necessary.

Phenytoin

Isoniazid inhibits the hepatic metabolism of phenytoin, resulting in increased plasma phenytoin concentrations and toxicity in some patients. Phenytoin toxicity occurs mainly in slow isoniazid inactivators and in patients receiving both isoniazid and aminosalicylic acid. Patients receiving isoniazid and phenytoin concurrently should be observed for evidence of phenytoin intoxication, and the dosage of the anticonvulsant should be reduced accordingly.

Serotonergic Agents

Isoniazid appears to have some MAO-inhibiting activity. In addition, iproniazid, another antituberculosis agent structurally related to isoniazid that also possesses MAO-inhibiting activity, reportedly has resulted in serotonin syndrome in at least 2 patients when given in combination with meperidine. Pending further experience, clinicians should be aware of the potential for serotonin syndrome when isoniazid is given in combination with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor therapy or other serotonergic agents.

Other Drugs

Aluminum hydroxide gel decreases GI absorption of isoniazid; isoniazid should be administered at least 1 hour before the antacid. Coordination difficulties and psychotic episodes have occurred in patients receiving isoniazid and disulfiram concurrently, probably as a result of alterations in dopamine metabolism; concurrent administration of the drugs should be avoided.

Side Effects

Isoniazid is generally well tolerated at currently recommended doses. However, patients who are slow acetylators of isoniazid and those with advanced HIV disease appear to have a higher incidence of some adverse effects. Also, patients whose nutrition is poor are at risk of peripheral neuritis, which is one of the most common adverse effects of isoniazid. Other neurological adverse effects include psychotic reactions and convulsions. Pyridoxine may be given to prevent or treat these adverse effects. Optic neuritis has also been reported. Transient increases in liver enzymes occur in 10 to 20% of patients during the first few months of treatment and usually return to normal despite continued treatment. Symptomatic hepatitis occurs in about 0.1 to 0.15% of patients given isoniazid as monotherapy, but this can increase with age, regular alcohol consumption, and in those with chronic liver disease. The influence of acetylator status is uncertain.

Elevated liver enzymes associated with clinical signs of hepatitis, such as nausea, vomiting, or fatigue, may indicate hepatic damage; in these circumstances, isoniazid should be stopped pending evaluation and should only be reintroduced cautiously once the hepatic function has recovered. Fatalities have occurred due to liver necrosis. Hematological effects reported on the use of isoniazid include various anemias, agranulocytosis, thrombocytopenia, and eosinophilia. Hypersensitivity reactions occur infrequently and include skin eruptions (including erythema multiforme), fever, and vasculitis. Other adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, constipation, pellagra, purpura, hyperglycemia, lupus-like syndrome, vertigo, hyperreflexia, urinary retention, and gynecomastia. Symptoms of overdosage include slurred speech, metabolic acidosis, hallucinations, hyperglycemia, respiratory distress or tachypnoea, convulsions, and coma; fatalities can occur.

Effects on the Blood

In addition to the effects mentioned above, rare reports of isoniazid’s adverse effects on the blood include bleeding associated with acquired inhibition of fibrin stabilization or factor XIII and red cell aplasia.

Effects on the CNS

In addition to the peripheral neuropathy that is a well-established adverse effect of isoniazid, effects on the CNS have also been reported, including ataxia and cerebellar toxicity, psychotic reactions (generally characterized by delusions, hallucinations, and confusion), and seizures, particularly after overdosage. Encephalopathy has been reported in dialysis patients. Encephalopathy may also be a symptom of pellagra, which may be associated with isoniazid treatment.

Effects on the Liver

Transient liver function abnormalities are common during the initial stages of antituberculous therapy with isoniazid and other first-line drugs, but serious hepatotoxicity can occur, necessitating a treatment change. Drug-induced hepatitis typically arises within weeks of starting therapy, and pinpointing the specific drug responsible can be challenging. Isoniazid and pyrazinamide are more likely to cause hepatotoxicity compared to rifampicin, with risk factors including alcoholism, older age, female gender, malnutrition, HIV infection, and chronic hepatitis B or C.

Research indicates that slow isoniazid acetylators may be at a higher risk of hepatotoxicity than fast acetylators. A multicenter study found a 1.6% incidence of hepatotoxic reactions among patients on a short-term regimen of isoniazid, rifampicin, and pyrazinamide. In contrast, the incidence was lower (1.2%) for those on a 9-month regimen of isoniazid and rifampicin. Children with severe disease had a 3.3% incidence of hepatotoxic reactions.

Guidelines recommend initial liver function tests for all patients and regular monitoring for those with existing liver conditions. The incidence of hepatotoxicity is lower in patients receiving isoniazid for prophylaxis compared to those treated for active disease. For example, only 0.15% of patients on prophylactic therapy experienced hepatotoxicity over seven years, while 1.25% did so during active treatment. Overall, careful monitoring and adherence to guidelines are crucial for managing potential liver complications during antituberculous therapy.

Effects on the Pancreas

Cases of isoniazid-induced pancreatitis have been rarely reported; pancreatitis resolved in these patients once treatment with isoniazid was stopped, and recurred on rechallenge. It is recommended if isoniazid-induced pancreatitis is proven that the drug should be permanently avoided. Chronic pancreatic insufficiency, after an acute episode, was reported in a patient given isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide and was considered to be a drug hypersensitivity reaction.

Effects on the Skin and Hair

Isoniazid causes cutaneous drug reactions in less than 1% of patients. These reactions include urticaria, purpura, acneform syndrome, lupus erythematosus-like syndrome (see below), and exfoliative dermatitis. Pellagra is also associated with isoniazid. Isoniazid was considered the most likely cause of alopecia in 5 patients receiving antituberculosis regimens, which also included rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide.

Lupus

Antinuclear antibodies have been reported to occur in up to 22% of patients receiving isoniazid; however, patients are usually asymptomatic, and overt lupoid syndrome is rare. The incidence of antibody induction has been reported to be higher in slow acetylators than in fast acetylators, but the difference was not statistically significant, and acetylator phenotype is not considered an important determinant of the risk of isoniazid-induced lupus. The syndrome appeared to be due to isoniazid itself rather than its metabolite acetyl isoniazid.

Nervous System Effects

Peripheral neuritis, usually preceded by paresthesia of the feet and hands, is the most common adverse effect of isoniazid and occurs most frequently in malnourished patients and those predisposed to neuritis (e.g., alcoholics, diabetics). Rarely, other adverse nervous system effects have also occurred, including seizures, toxic encephalopathy, muscle twitching, ataxia, stupor, tinnitus, euphoria, memory impairment, separation of ideas and reality, loss of self-control, dizziness, and toxic psychosis.

Neurotoxic effects may be prevented or relieved by the administration of 10-50 mg of pyridoxine hydrochloride daily during isoniazid therapy, and pyridoxine should be administered in malnourished patients, pregnant women, and those predisposed to neuritis (e.g., HIV-infected individuals). In addition, optic neuritis and atrophy have been reported with isoniazid.

Sensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity reactions, including fever, skin eruptions (morbilliform, maculopapular, purpuric, or exfoliative), lymphadenopathy, vasculitis, and, rarely, hypotension, have occurred rarely with isoniazid, usually 3-7 weeks following initiation of therapy.

All drugs should be discontinued at the first sign of a hypersensitivity reaction. If isoniazid is reinstituted, it should be restarted in small and gradually increasing doses only after symptoms have cleared. If there is any indication of a recurrence of hypersensitivity, it should be discontinued immediately.

Pyridoxine Deficiency

Pyridoxine deficiency associated with isoniazid in doses of 5 mg/kg daily is uncommon. Patients at risk of developing pyridoxine deficiency include those with diabetes, uremia, alcoholism, HIV infection, and malnutrition.,t Supplementation with pyridoxine should be considered for these at-risk groups as well as for pregnant women and patients with seizure disorders. For the prophylaxis of peripheral neuritis it is common practice to give pyridoxine 10 mg daily, although 6 mg daily might be sufficient. However, in one patient, a dose of pyridoxine 10 mg daily failed to prevent psychosis, the symptoms of which only resolved after stopping isoniazid and increasing the pyridoxine dosage to 100 mg daily.

Other Adverse Effects

Other reported adverse effects of isoniazid include nausea, vomiting, epigastric distress, dry mouth, pyridoxine deficiency, pellagra, hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, urinary retention, and gynecomastia in males. Systemic lupus erythematosus-like syndrome and rheumatic syndrome with arthralgia have also occurred. IM administration of isoniazid has caused irritation at the site of injection.

Treatment of Adverse Effects

Pyridoxine hydrochloride 10 mg daily is usually recommended for prophylaxis of peripheral neuritis associated with isoniazid, although up to 50 mg daily may be used. A dose of 50 mg three times daily may be given for treatment of peripheral neuritis if it develops. Nicotinamide has been given, usually with pyridoxine, to patients who develop pellagra. Isoniazid doses of 1.5 g or more are potentially toxic and doses of 10 to 15 g may be fatal without appropriate treatment. Treatment of overdosage is symptomatic and supportive and consists of activated charcoal, correction of metabolic acidosis, and control of convulsions. Large doses of pyridoxine may be needed intravenously for control of convulsions (see below) and should be given with diazepam. Isoniazid is removed by hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

Overdosage

Overdosage of isoniazid has produced nausea, vomiting, dizziness, slurred speech, blurred vision, and visual hallucinations (including bright colors and strange designs). Symptoms of overdosage usually occur within 30 minutes to 3 hours following ingestion of the drug. After marked overdosage, respiratory distress, and CNS depression, progressing rapidly from stupor to coma, severe intractable seizures, metabolic acidosis, acetonuria, and hyperglycemia have occurred. If untreated or treated inadequately, isoniazid overdosage may be fatal. Isoniazid-induced seizures are thought to be associated with decreased ?-aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentrations in the CNS, possibly resulting from inhibition by isoniazid of brain pyridoxal-5-phosphate activity.

Treatment of Overdose

In the management of isoniazid overdosage, an airway should be secured and adequate respiratory exchange established immediately. Seizures may be controlled with IV administration of diazepam or short-acting barbiturates and a dosage of pyridoxine hydrochloride equal to the amount of isoniazid ingested. Generally, 1-4 g of pyridoxine hydrochloride is given IV, followed by 1 g IM every 30 minutes until the entire dose has been given. If seizures are controlled and overdosage is recent (within 2-3 hours), the stomach should be emptied by gastric lavage.

Blood gases, serum electrolytes, glucose, and BUN determinations should be performed. Blood should be typed and cross-matched in case hemodialysis is required. IV sodium bicarbonate should be administered to control metabolic acidosis and repeated as needed; the dosage should be adjusted based on laboratory test results. Pyridoxine has also had a beneficial effect on correcting acidosis in some patients, possibly by controlling seizures and resulting lactic acidosis.

Pyridoxine has been effective in treating isoniazid-induced seizures as well as other mental status changes associated with isoniazid overdosage. In several patients who remained comatose following initial treatment of seizures with diazepam and pyridoxine, administration of an additional 3- to 5-g dose of pyridoxine hydrochloride after 36-42 hours of coma resulted in complete awakening within 30 minutes. The fact that administration of high doses of pyridoxine can result in adverse neurologic effects should be considered whenever the drug is used in the treatment of isoniazid-induced seizures and/or coma.

Forced osmotic diuresis should be initiated as soon as possible following isoniazid overdosage to increase renal clearance of the drug and should be continued several hours after clinical improvement to ensure complete clearance of the drug and prevent relapse. Fluid intake and output should be monitored. In severe cases, hemodialysis or, if hemodialysis is not available, peritoneal dialysis should be used in conjunction with forced diuresis. In addition, measures should be taken to protect against hypoxia, hypotension, and aspiration pneumonitis.

Storage

Isoniazid preparations should be protected from light, air, and excessive heat. Isoniazid tablets should be stored in well-closed, light-resistant containers at a temperature less than 40°C, preferably between 15-30°C. Tablets containing the fixed combination of rifampin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide (Rifater®) should be protected from excessive humidity and stored at 15-30°C. Isoniazid injection should be protected from light and stored at a temperature less than 40°C, preferably between 15-30°C; freezing should be avoided. At low temperatures, isoniazid in solution tends to crystallize, and the injection should be warmed to room temperature to redissolve the crystals prior to use.

Preparations

Isoniazid Powder Oral Solution 50 mg/5 mL Isoniazid Syrup, (with sorbitol 70%) Allscripts Carolina Medical Versa Tablets 100 mg 300 mg Parenteral Injection 100 mg/mL Nydrazid®, (with chlorobutanol 0.25%) Sandoz Isoniazid Combinations Oral Capsules 150 mg with Rifampin 300 mg Rifamate®, Aventis Tablets 50 mg with Pyrazinamide 300 Rifater®, (with povidone and mg and Rifampin 120 mg propylene glycol) Aventis

Single-ingredient Preparations

| Country | Drug Names |

|---|---|

| Argentina | Isoniac |

| Belgium | Nicotibine, Rimifon |

| Canada | Isotamine |

| Czech Republic | Nidrazid |

| Finland | Tubilysin |

| France | Rimifon |

| Germany | Dipasic, Gluronazid, Isozid comp N, Isozid, Tb-Phlogin cum B6, tebesium-s, tebesium |

| Greece | Dianicotyl, Isozid, Nicozid |

| Hong Kong | Trisofort |

| Hungary | Isonicid |

| India | Isokin, Isonex, Rifacom E-Z |

| Israel | Inazid |

| Italy | Cin, Nicazide, Nicizina, Nicozid |

| Japan | Hydra, Hydrazide |

| Mexico | Dipasic, Erbazid, Hidrasix, Pas Hain, Valifol |

| Portugal | Hidrazida |

| Spain | Anidrasona, Cemidon B6, Cemidon, Dipasic, Hidrastol, Pyreazid, Rimifon |

| Sweden | Tibinide |

| Switzerland | Rimifon |

| Thailand | Myrin-P, Myrin |

| United Kingdom | Inapsade, Rimifon |

| United States | Laniazid, Nydrazid |

Multi-ingredient Preparations

| Country | Drug Names |

|---|---|

| Argentina | Bacifim, Rifinah, Risoniac |

| Austria | Isoprodian, Myambutol-INH, Rifater, Rifoldin INH, Rimactan + INH |

| Brazil | Fluodrazin F, Isoniaton |

| Canada | Rifater |

| France | Myambutol-INH, Rifater, Rifinah |

| Germany | EMB-INH, Etibi-INH, Iso-Eremfat, Isoprodian, Myambutol-INH, Rifa/INH, Rifater, Rifinah, tebesium Duo, tebesium Trio |

| Greece | Oboliz, Rifater, Rifinah, Rimactazid |

| Hong Kong | Ricinis, Rifater, Rifinah |

| Hungary | Rifazid |

| India | Akt-3, Akt-4, Arzide, Bicox-E, Combunex, Coxina-3, Coxina-4, Coxinex, Cx-3, Cx-4, Cx-5, Gocox Compound, Gocox-3, Gocox-4, Inabutol Forte, Inapas, Ipcacin Kid, Ipcazide, Isokin-300, Isokin-T Forte, Isorifam, Myconex, R-Cinex Z, R-Cinex, RHZ-Plus, Rifa E, Rifa, Rifacomb Plus, Rifacomb, Rimactazid + Z, Rimpazid, Siticox-INH, Tibirim INH, Tricox, Wokex-2, Wokex-3, Wokex-4, Xeed-2, Xeed-3E, Xeed-4 |

| Ireland | Rifater, Rifinah, Rimactazid |

| Italy | Emozide B6, Etanicozid B6, Etibi-INH, Miazide B6, Miazide, Rifanicozid, Rifater, Rifinah |

| Malaysia | Rimactazid |

| Mexico | Arpisen, Finater, Finateramida, Isonid, Myambutol-INH, Rifater, Rifinah |

| Monaco | Dexambutol-INH |

| Netherlands | Rifinah |

| New Zealand | Rifinah |

| Portugal | Rifater, Rifinah, Tuberen |

| Russia | Phthizoetham (Фтизоэтам), Phthizopiram (Фтизопирам), Rifacomb (Рифакомб), Rifacomb Plus (Рифакомб Плюс) |

| South Africa | Isoprodian; Mynah; Myrin Plus; Myrin; Pyrifin; Rifafour; Rifater; Rifinah; Rimactazid; Rimcure; Tuberol |

| Singapore | Rifater; Rifinah; Rimactazid |

| Spain | Amiopia; Duplicalcio 150; Duplicalcio B12; Duplicalcio Hidraz; Duplicalcio; Isoetam; Poli Biocatines; Rifater; Rifazida; Rifinah; Rimactazid; Rimcure; Rimstar; Tisobrif; Victogon |

| Sweden | Rimactazid; Rimcure; Rimstar |

| Switzerland | Myambutol-INH; Rifater; Rifinah; Rifoldine-INH; Rimactazide + Z; Rimactazide |

| Thailand | Ricinis; Rifafour; Rifamiso; Rifampyzid; Rifater; Rifinah; Rimactazid; Rimcure 3-FDC; Rimstar |

| United Kingdom | Mynah; Rifater; Rifinah; Rimactazid |

| United States | IsonaRif; Rifamate; Rifater; Rimactane/INH Dual Pack |