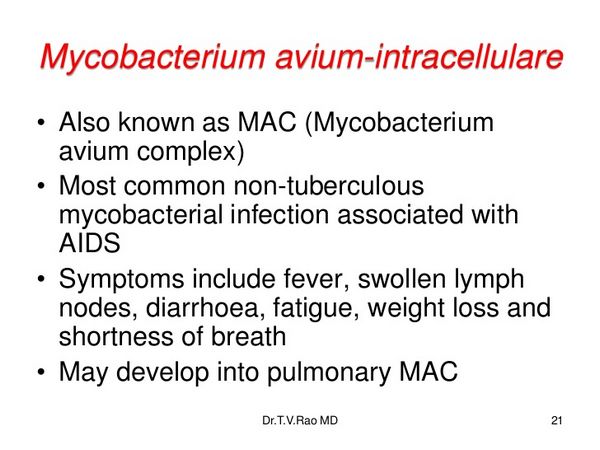

Mycobacterium avium Complex (MAC) Infections

Primary Prevention of Disseminated MAC Infection

Rifabutin is used alone or in conjunction with azithromycin to prevent or delay the development of Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) bacteremia and disseminated infections (primary prophylaxis) in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; rifabutin is designated an orphan drug by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this use.

Prevention of disseminated MAC disease is an important goal in the management of patients with HIV infection and low helper/inducer (CD4+, T4+) T-cell counts because of the frequency with which the disease occurs in such patients and its associated morbidity. Current evidence indicates that MAC causes disseminated disease in a substantial proportion of HIV-infected patients and that prophylaxis with rifabutin, alone or combined with azithromycin, can reduce substantially the frequency of M. avium complex bacteremia and ameliorate clinical manifestations of the disease in patients with AIDS. Azithromycin or clarithromycin also is used alone to prevent disseminated MAC infection in HIV-infected patients. Prophylaxis with rifabutin or clarithromycin has been shown to improve survival in patients with advanced HIV infection.

In controlled studies, patients with AIDS who received primary prophylaxis with rifabutin were one-half to one-third as likely to develop MAC bacteremia and its clinical manifestations as those receiving placebo. In 2 placebo-controlled studies in patients with AIDS20 whose CD4+ T-cell counts were 200/mm3 or less, MAC bacteremia occurred in 9-13% of patients receiving rifabutin prophylaxis compared with 22-28% of those receiving placebo. In addition, patients given the drug demonstrated fewer manifestations of disseminated MAC infection, including fever, night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, abdominal pain, anemia, and hepatic abnormalities.

Most cases of therapeutic failure (e.g., development of MAC bacteremia despite rifabutin prophylaxis) occurred in patients whose CD4+ T-cell count was 100/mm3 or less on enrollment into the study. Although mortality rates in the individual studies were not significantly reduced with rifabutin prophylaxis, an analysis of the combined double-blind and open follow-up periods of these studies indicated that prophylaxis with the drug was associated with improved survival over a period of approximately 700 days of follow-up.

Rifabutin also has been used in conjunction with azithromycin for the prevention of disseminated infection caused by MAC in patients with advanced HIV infection. In a randomized, comparative study in patients with advanced HIV infection (CD4+ T-cell counts less than 100/mm3), prophylaxis with rifabutin (300 mg daily), azithromycin (1. g once weekly), or both drugs concomitantly was associated with a cumulative incidence of MAC infection at 1 year of 15..6, or 2.8%, respectively.

The risk of MAC infection (after adjustment for baseline CD4+ counts) in patients receiving azithromycin prophylaxis was 47% lower than that with rifabutin prophylaxis, while prophylaxis with both drugs reduced the risk by 72% compared with rifabutin alone; survival among the 3 groups was similar. Although the overall incidence of adverse effects was similar among the 3 groups (i.e., 76, 86, or 90% of patients receiving rifabutin, azithromycin, or combined rifabutin-azithromycin prophylaxis, respectively), dose-limiting adverse effects (principally GI effects) occurred more frequently with combined azithromycin-rifabutin prophylaxis than with rifabutin or azithromycin alone.

Current evidence suggests that primary prophylaxis against disseminated MAC infection is superior to efforts aimed at early detection and treatment of the disease in terms of survival benefit. The Prevention of Opportunistic Infections Working Group of the US Public Health Service and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (USPHS/IDSA) currently recommends that primary prophylaxis against MAC disease be given to HIV-infected adults and adolescents (13 years of age or older) whose CD4+ counts are less than 50/mm3. Severely immunocompromised HIV-infected children younger than 13 years of age also should receive primary prophylaxis against MAC disease according to the following age-specific CD4+ T-cell counts: children 6-13 years of age, less than 50/mm3; children 2-6 years of age, less than 75/mm3; children 1-2 years of age, less than 500/mm3; and children younger than 1 year of age, less than 750/mm3.

The USPHS/IDSA currently states that clarithromycin or azithromycin alone is the preferred regimen for primary prophylaxis; alternatively, if these drugs cannot be tolerated, rifabutin may be used alone. In selecting a prophylactic regimen, consideration should be given to the potential for clinically important interactions between rifabutin, macrolide antibiotics (e.g., azithromycin, clarithromycin), and other drugs commonly used in HIV-infected patients, including HIV protease inhibitors (e.g., amprenavir, indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir) and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (e.g., delavirdine, efavirenz, nevirapine).

Although the combination of azithromycin and rifabutin is more effective than azithromycin alone, the USPHS/IDSA currently does not recommend routine prophylaxis with the combination because of additional cost, increased incidence of adverse effects, potential for drug interactions, and absence of a difference in survival in patients receiving the combination compared with azithromycin alone. In addition, the USPHS/IDSA states that the combination of clarithromycin and rifabutin should not be used for primary MAC prophylaxis since such combined therapy is no more effective than clarithromycin alone and is associated with a higher incidence of adverse effects.

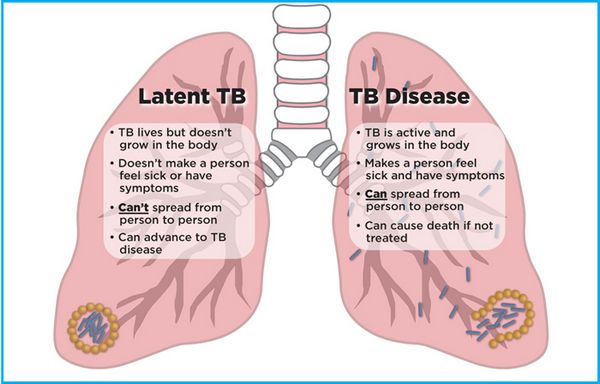

Before MAC prophylaxis is initiated, patients should be assessed to ensure that they do not have active infection with MAC, M. tuberculosis, or other mycobacterial diseases. If such active disease is present, appropriate anti-infective treatment should be initiated. Preventive therapy with rifabutin should not be initiated in patients with active M. tuberculosis since administration of the drug as sole antimycobacterial therapy in such patients would likely lead to development of tuberculosis that is resistant to both rifabutin and rifampin. Patients who develop symptoms compatible with active tuberculosis while receiving rifabutin prophylaxis should be evaluated immediately and appropriate therapy instituted with an effective combination of antituberculosis agents.

Current evidence indicates that primary MAC prophylaxis can be discontinued with minimal risk of developing disseminated MAC disease in HIV-infected adults and adolescents who have responded to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with an increase in CD4+ T-cell counts to greater than 100/mm3 that has been sustained for at least 3 months. The USPHS/IDSA states that discontinuance of primary prophylaxis is recommended in adults and adolescents meeting these criteria because prophylaxis appears to add little benefit in terms of disease prevention for MAC or bacterial infections, and discontinuance reduces the medication burden, the potential for toxicity, drug interactions, selection of drug-resistant pathogens, and cost. However, the USPHS/IDSA states that primary MAC prophylaxis should be restarted in adults and adolescents if CD4+ T-cell counts decrease to less than 50-100/mm3.

Treatment and Secondary Prevention of Disseminated MAC Infection

Rifabutin is designated an orphan drug by FDA for use in the treatment or prevention of recurrence of disseminated MAC infections. For information on the use of rifabutin as a component of multiple-drug regimens for the treatment or secondary prevention of disseminated MAC infections.

Tuberculosis

Active Tuberculosis

Rifabutin is used as an alternative to rifampin in multiple-drug regimens for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis.

The American Thoracic Society (ATS), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) currently recommend several possible multiple-drug regimens for the treatment of culture-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. These regimens have a minimum duration of 6 months (26 weeks), and consist of an initial intensive phase (2 months) and a continuation phase (usually either 4 or 7 months). Rifabutin is used as an alternative to rifampin and is considered a first-line antituberculosis agent for use in these regimens. The ATS, CDC, and IDSA state that use of rifabutin in the treatment of tuberculosis generally should be reserved for use in patients who cannot receive rifampin because of intolerance or because they are receiving other drugs (especially antiretroviral agents) that have a clinically important interaction with rifampin.

Limited data in patients with previously untreated tuberculosis suggest that the efficacy of rifabutin in short-course (6-9-month) antituberculosis regimens compares favorably with that of rifampin in terms of bacteriologic conversion of sputum cultures and clinical improvement. Results of uncontrolled studies in a limited number of patients also suggest that rifabutin may provide some benefit in patients with multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis, including those whose disease is resistant to rifampin and/or isoniazid. Additional well-controlled clinical trials are needed to confirm the efficacy of rifabutin for infections in patients with rifampin-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis.

HIV-infected Individuals

Data from a limited number of studies in patients with HIV infection and pulmonary tuberculosis also suggest similar efficacy and safety of short-course (6-month) antituberculosis regimens containing either rifampin or rifabutin in conjunction with isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. However, there is evidence that use of antituberculosis regimens that include once- or twice-weekly administration of rifamycins (e.g., rifabutin, rifampin, rifapentine) in HIV-infected patients with CD4+ T-cell counts less than 100/mm3 is associated with an increased risk of acquired rifamycin resistance. Therefore, until additional data are available regarding this issue, the CDC recommends that HIV-infected individuals with CD4+ T-cell counts less than 100/mm3 not receive rifamycin regimens for the treatment of active tuberculosis that involve once- or twice-weekly administration. These individuals should receive daily therapy during the initial phase, and daily or 3-times weekly regimens during the second phase; directly observed therapy also is recommended for both the daily and 3-times weekly regimens.

The fact that concomitant use of rifamycins and certain antiretroviral agents (e.g., HIV protease inhibitors, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NNRTIs]) can affect plasma concentrations of the antituberculosis agent and/or the antiretroviral agents must be considered when antituberculosis therapy is indicated for the treatment tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients.

Because of the pharmacokinetic interactions between rifamycins and HIV protease inhibitors or NNRTIs and because rifabutin is a less potent inducer of cytochrome P-450 (CYP) isoenzymes than rifampin, the CDC and other experts previously stated that use of rifampin was contraindicated in patients receiving HIV protease inhibitors or NNRTIs and that use of rifabutin-containing regimens was the preferred alternative for the treatment of active tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients receiving these antiretroviral agents. However, the CDC and some experts now suggest that there are specific circumstances when HIV-infected patients with active tuberculosis can receive rifampin concomitantly with certain HIV protease inhibitors or certain NNRTIs.

Rifampin can be used in patients receiving the following antiretroviral regimens (with appropriate dosage adjustments): efavirenz and 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; ritonavir and 1 or 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; or an antiretroviral regimen that includes both ritonavir and saquinavir.

Rifabutin-containing regimens (with appropriate dosage adjustments) offer an alternative for HIV-infected patients receiving these and other antiretroviral regimens. Some advantages of rifabutin-containing antituberculosis regimens in HIV-infected patients include (1) less potential for drug interactions with drugs commonly prescribed in such patients (e.g., protease inhibitors, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NNRTIs], azole antifungal drugs, anticonvulsants, methadone), (2) potentially more reliable absorption in patients with advanced HIV disease, and (3) more tolerability in patients with rifampin-induced hepatotoxicity.

Latent Tuberculosis Infection

Rifabutin (with appropriate dosage adjustments) is used alone in a 4-month regimen or in conjunction with pyrazinamide in a 2- to 3-month regimen to prevent the development of clinical tuberculosis in HIV-infected adults and adolescents.

Previously, “preventive therapy” or “chemoprophylaxis” was used to describe a simple drug regimen (e.g., isoniazid monotherapy) used to prevent the development of active tuberculosis disease in individuals known or likely to be infected with M. tuberculosis. However, since use of such a regimen rarely results in true primary prevention (i.e., prevention of infection in individuals exposed to infectious tuberculosis), the ATS and CDC currently state that “treatment of latent tuberculosis infection” rather than “preventive therapy” more accurately describes the intended intervention and potentially will result in greater understanding and more widespread implementation of this tuberculosis control strategy.

While therapy with rifabutin in tuberculin-positive patients with HIV infection has not been evaluated in clinical trials, the ATS and CDC state that the use of rifabutin in these short-course, multiple-drug regimens for treatment of latent tuberculosis infection is valid for the same scientific principles that support its use in the treatment of active tuberculosis. When use of rifabutin is being considered for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV-infected patients, the possibility that drug regimens or dosages may have to be altered because of clinically important pharmacokinetic interactions between rifabutin and certain antiretroviral agents (e.g., HIV protease inhibitors, NNRTIs) should be considered.