Recommendations for use of antiretroviral agents for the treatment of HIV infection in pregnant HIV-infected women generally are the same as those for nonpregnant HIV-infected adults, and women should receive optimal antiretroviral therapy regardless of pregnancy status. Although zidovudine is the only antiretroviral agent currently labeled for use in pregnant women, most clinicians do not consider pregnancy a contraindication for multiple-drug antiretroviral therapy when such therapy is indicated, especially during the second or third trimester.

Therefore, multiple-drug antiretroviral therapy should be discussed with and offered to all HIV-infected pregnant women for their own health. In addition, because there is evidence that use of a regimen that includes both antepartum and intrapartum zidovudine therapy in the pregnant woman and zidovudine therapy in the neonate (study PACTG 076 regimen) can decrease the risk of perinatal transmission of HIV, this 3-part zidovudine regimen for prevention of maternal-fetal transmission of HIV should be discussed with and offered to all HIV-infected pregnant women.

Since 1995, the US Public Health Service (USPHS), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have recommended that universal HIV counseling and HIV testing (with consent) be considered a standard of care for all pregnant women in the US. This recommendation was made to facilitate optimal antiretroviral treatment of HIV-infected pregnant women, allow appropriate use of a prophylaxis regimen to decrease the risk of perinatal transmission of HIV, and facilitate early identification and optimal treatment of perinatally infected children.

ACOG advocates extending to all women of childbearing age the opportunity to receive preconceptional counseling as a component of routine primary medical care. For women with HIV infection, preconceptional counseling should focus on maternal infection status, viral load, and immune status; initiation or modification of antiretroviral therapy prior to conception; education and counseling regarding perinatal transmission risks and prevention strategies; and selection of effective and appropriate contraceptive methods to reduce the likelihood of unintended pregnancy.

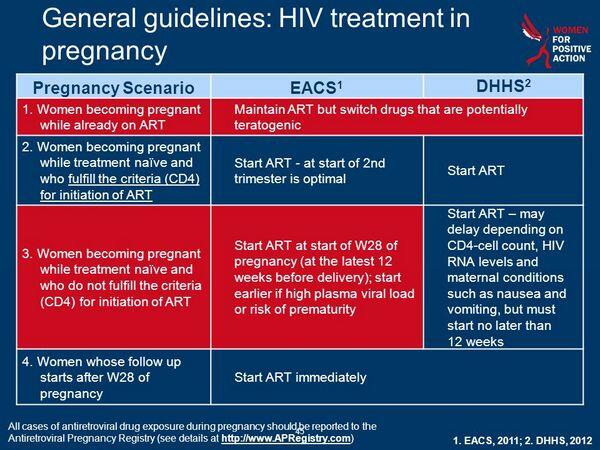

A decision to administer antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy and the most appropriate drugs to include in the antiretroviral regimen should be made on an individual basis taking into account the clinical, virologic, and immunologic status of the woman, the stage of pregnancy, and the known and unknown benefits and risks to the woman and her fetus. Antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy is complex since pregnancy may affect decisions regarding when to initiate antiretroviral therapy and which drugs to include in the antiretroviral regimen and the potential risks of the drugs during pregnancy must be weighed against the proven benefit of antiretroviral therapy for the health of the woman and the benefits of reducing the risk of HIV transmission to her child.

Ideally, decisions regarding management of HIV infection during pregnancy should involve collaboration between an HIV specialist, the pregnant woman, and her obstetrician. Discussions of treatment options and recommendations should be noncoercive, and the final decision regarding use of antiretroviral agents during pregnancy should be made by the woman. A pregnant woman’s decision to refuse antiretroviral therapy or to accept use of zidovudine alone should not result in punitive action or denial of care.

Because the first trimester of pregnancy (especially the first 8 weeks) is the most vulnerable time with respect to teratogenicity, some clinicians may recommend and some women may wish to delay initiation of antiretroviral therapy until after 10-12 weeks’ gestation. However, if clinical, virologic, or immunologic parameters are such that initiation of antiretroviral therapy would be recommended if the patient were not pregnant, then many experts would recommend initiating antiretroviral therapy regardless of gestational age. This decision should be made only after careful consideration and discussion regarding the health status of the woman and the potential benefits and risks of delaying initiation of therapy for several weeks.

Because nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy may affect compliance and/or GI absorption of oral antiretroviral agents, this may be a factor to consider when deciding whether to initiate or delay initiation of such therapy during the first trimester.

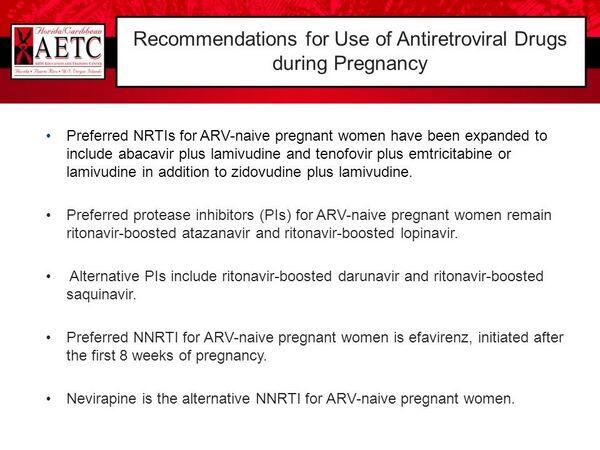

In women of reproductive age, selection of an antiretroviral regimen should take into account the possibility of planned or unplanned pregnancy. Efavirenz-containing regimens should be avoided in pregnant women because teratogenic effects have been observed in primates at efavirenz exposures similar to the recommended human dosage. Insufficient data exist to either support or refute teratogenic risk of other antiretroviral agents when administered during the first 10-12 weeks’ gestation.

However, the combination of didanosine and stavudine should be avoided as first-line therapy in pregnant women; several maternal deaths secondary to lactic acidosis have been reported in women receiving long-term therapy with this combination. The commercially available oral solution of amprenavir contains propylene glycol (550 mg/mL) and is contraindicated in pregnant women, although amprenavir oral capsules can be used during pregnancy if use of amprenavir is considered necessary.

Some clinicians recommend continuing antiretroviral therapy even during the first trimester, if possible, since there is concern that discontinuance of antiretroviral therapy could result in a rebound in viral load that theoretically could potentiate disease progression in the woman or increase the risk of early in utero HIV transmission to the fetus. If antiretroviral therapy is discontinued during the first trimester for any reason, all antiretroviral agents should be discontinued simultaneously and reintroduced together to minimize the development of resistance to the drugs.

Safety of Antiretrovirals during Pregnancy

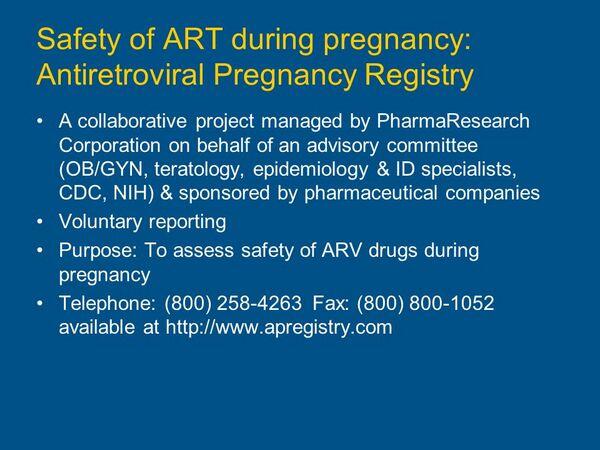

Data from human (abacavir, didanosine, lamivudine, nevirapine, zidovudine) and animal (amprenavir, delavirdine, efavirenz, indinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, stavudine, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, zalcitabine) studies indicate that all antiretroviral agents tested to date cross the placenta. While animal reproduction studies performed using some antiretroviral agents (e.g., atazanavir, didanosine, enfuvirtide, emtricitabine, indinavir, lamivudine, lopinavir and ritonavir, nelfinavir, nevirapine, ritonavir, saquinavir, stavudine) have not revealed evidence of teratogenicity, results of similar animal studies have indicated that there is a potential risk for teratogenicity (delavirdine, efavirenz, zalcitabine) or embryotoxicity (abacavir, amprenavir, delavirdine, indinavir, lopinavir and ritonavir, ritonavir, stavudine, zalcitabine, zidovudine) with some of these agents. However, the predictive value of in vitro or animal tests for adverse effects in humans is not known, and the teratogenic potential of antiretroviral agents in humans has not been fully evaluated

Safe use of zidovudine in pregnant women has been established and considerable information is available regarding use of the drug in pregnant women. Selection of other antiretroviral agents for multiple-drug regimens in pregnant women should be individualized and based on the most recent information available from preclinical and clinical studies of the individual drugs.

Although studies are ongoing, data are limited to date regarding safety and efficacy of most antiretrovirals (other than zidovudine) or use of multiple-drug antiretroviral regimens in pregnant women.

Results of one retrospective study evaluating pregnancy outcomes in a limited number of HIV-infected women who received antiretroviral regimens (2 NRTIs with or without HIV protease inhibitors) indicate that almost 80% of women developed one or more typical adverse effects (e.g., anemia, nausea and vomiting, increased serum concentrations of liver enzymes, hyperglycemia). Data are conflicting regarding whether antiretroviral therapy is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm delivery.

Although a possible association between antiretroviral therapy and preterm births was noted in the retrospective study, it is unclear whether the stage of HIV disease or some other variable may have contributed to premature births in these women.

Other studies have shown elevated preterm birth rates in HIV-infected women who have not received any antiretroviral therapy. Results of a large pooled analysis of 7 clinical studies that included 2123 HIV-infected pregnant women who received antenatal antiretroviral therapy and 1143 women who did not receive such therapy indicate that use of multiple-drug regimens is not associated with increased rates of preterm labor, low birth weight, low Apgar scores, or stillbirth compared with no treatment or monotherapy. However, HIV-infected pregnant women who are receiving antiretroviral therapy should receive careful, regular monitoring for pregnancy complications and potential toxicities.