Essentials of Diagnosis

- “Sulfur granules” in specimens and sinus tract drainage: hard, irregularly shaped, yellow particles measuring from 1 to 5 mm in size

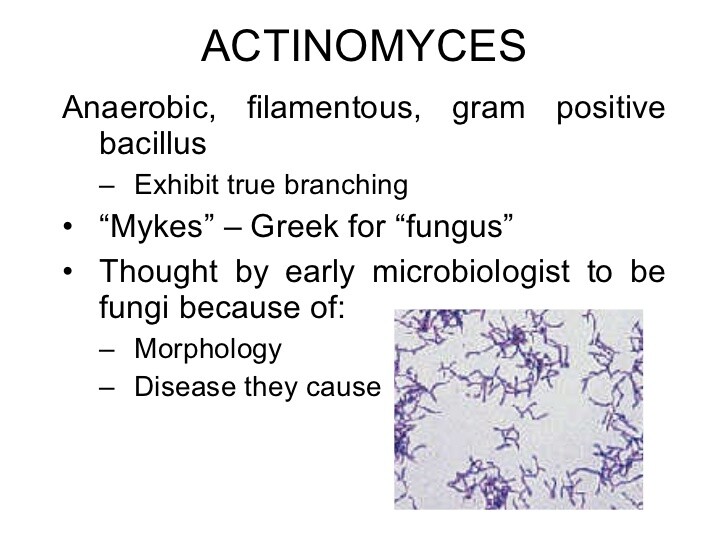

- Gram-positive branching filaments arranged in ray-like projections under the microscope

- Colonies with characteristic “molar tooth” appearance

- Production of extensive fibrosis with “woody” induration

- No specific antibody or antigen detection tests

General Considerations

Epidemiology

The Actinomyces species are facultative anaerobes that commonly inhabit the oral cavity, the gastrointestinal tract, and the female genital tract, where they exist as commensals.

Diversity within this genus is broad, which has led to taxonomic revision and reclassification of some species as members of the Arcanobacterium genus, eg, Actinomyces pyogenes.

Disease occurs when mechanical insult disrupts the mucosal barrier or organisms gain access to privileged sites. For example, actinomycosis commonly occurs after dental procedures, trauma, surgery, or aspiration.

Actinomyces israelii causes the majority of human disease owing to this genus, but other species, including Actinomyces naeslundii, Actinomyces viscosus, Actinomyces enksonii, Actinomyces odontolyticus, and Actinomyces meyeri have also been implicated. Actinomycosis is threefold more common in men than women.

Microbiology

See earlier introductory comments.

Pathogenesis

After inoculation into submucosal tissues, infection spreads slowly across anatomic boundaries, forming chronic, destructive abscesses and sinus tracts surrounded by thick fibrotic tissue, creating what is often described as “woody” induration. Lesions enlarge, become soft and fluctuant, and then suppurate, discharging purulent material containing granules. The neutrophil is the dominant responding leukocyte cell type; however, granulomata form over time. As the disease progresses, fistulas may extend from the abscess to either the skin or, less commonly, bone.

Actinomyces infections are usually polymicrobial. Multiple other organisms, including Actinobacillus, Eikenella, Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, and Capnocytophaga spp., members of the Enterobacteriaceae, staphylococci, and streptococci, are usually present in various combinations. These organisms may exert a synergistic effect on the disease process by secreting collagenase and hyaluronidase and thus facilitating extension of the lesion. Actinomyces virulence factors are not well understood. Actinomyces fimbriae may play an important role in bacterial self- or coaggregation with other oral bacterial species.

Clinical Findings

There are three major clinical presentations and types of disease: cervicofacial (~ 50% of all cases), abdominal (~ 20%), and thoracic (~ 15%).

Cervicofacial Disease

Cervicofacial actinomycosis usually follows dental or gingival manipulations or intraoral trauma. The most common site of involvement is the perimandibular region, where soft tissue swelling, abscess, or mass lesions can occur. Pain and fever are variably present. Actinomycosis can also cause periapical dental infections and sinusitis, especially of the maxillary sinus, as well as soft tissue infections of the head, neck, salivary glands, thyroid, external ear, and temporal bone.

Abdominal Disease

Abdominal disease usually follows gastrointestinal surgery, particularly emergency gall bladder and colonic surgery, appendicitis, or foreign-body penetration. Ileocecal involvement, which often follows appendicitis, is seen most frequently. Infection is indolent with symptoms reported from 1 month to 2 years before a definitive diagnosis. Associated findings include weight loss, fever, palpable tender mass, visible sinus tracts with drainage, or fistulas. Fistulas invading the abdominal wall or perineum form in approximately one-third of abdominal actinomycotic abscesses. Unless draining sinus tracts are present, surgery is required for diagnosis.

Thoracic Disease

Thoracic disease usually follows aspiration of infected oral material. However, direct extension from cervicofacial or abdominal disease can occur. The usual presentation is either a mass or pneumonia. Occasionally there is pleural involvement. The disease has an insidious onset and a subacute course. Typical symptoms include cough, hemoptysis, chest wall discomfort, fever, and weight loss. Radiographic findings are variable, including patchy infiltrates, mass lesions, or cavitary lesions. Empyema, osteomyelitis, and draining fistulous tracts can occur when there is extension directly into the pleural space, ribs, and chest wall. In the presence of pleural or chest wall involvement, diagnosis should not be difficult. However, because Actinomyces spp. are members of the normal oral flora, organisms cultured from sputum or bronchoscopic washings are not diagnostic. Diagnosis requires percutaneous needle aspiration, bronchoscopic biopsy, or open-lung biopsy.

Other Manifestations

Other less frequent presentations include pelvic actinomycosis, which has been recognized with greater frequency since its association with the use of intrauterine contraceptive devices. Clinical disease may take the form of endometritis, salpingo-oophoritis, or tubo-ovarian abscess. Liver, bone, pericardial, endocardial, CNS, and perianal involvement has also been reported.

Diagnosis

“Sulfur granules” are hard, irregularly shaped yellow particles that range in size from 0.1 to 5 mm. Microscopically, they appear as masses of bacterial filaments that may be arranged in ray-like projections. Their presence is typical, but not unique to this disease. Other organisms such as Nocardia spp., Streptomyces spp., and staphylococci in botryomycosis may form similar granules. A definitive diagnosis is made by growing the organism from an appropriate specimen in anaerobic culture media.

Timely procurement of specimens before initiation of antimicrobial therapy and submission to the laboratory using anaerobic transport kits optimize recovery of the organism by culture. Tissue, pus, or sulfur granules are the specimens of choice, and swabs should be avoided because the cotton filaments may be confused on microscopy with the organism. Multiple specimens should be obtained because organisms may be scarce in pathology specimens.

Growth usually appears within 5-7 days but can take as long as 2-4 weeks, so the lab should be alerted if actinomycosis is suspected. Growth plate media containing 5% sheep blood or rabbit blood supplemented with hemin and vitamin K should be used. However, other types of media including anaerobic blood culture medium, enriched thioglycolate medium, and chopped meat-glucose medium will support the growth of these organisms. Plates should be incubated at 35 to 37 °C in an anaerobic chamber. Often colonies are viewed first as “spiderlike” in appearance and mature to resemble a “molar tooth.” Biochemical tests are performed to distinguish the various species. There are no specific antibody or antigen detection tests.

Differential Diagnosis

Cervicofacial actinomycosis is often clinically misdiagnosed as a tumor, tuberculosis, or fungal infection. Actinomycosis often imitates a carcinoma, sarcoma, diverticular abscess, inflammatory bowel disease, or tuberculosis. Thoracic actinomycosis must be differentiated from other bacterial disease (tuberculosis and nocardiosis), systemic mycoses, and neoplastic disease.

Treatment

Penicillin is the drug of choice for actinomycosis (Box 4). Prolonged therapy is necessary to achieve a cure and minimize relapse. Intravenous penicillin G for 2-6 weeks followed by oral penicillin for 6-12 months is a reasonable regimen. Treatment should extend beyond the resolution of measurable disease. Long-term therapy is necessary because of the amount of reactive fibrosis formed by infection. Relapse is common especially after a short course of empiric antibiotic therapy. For patients with penicillin allergies, tetracycline is the preferred agent. Minocycline erythromycin and clindamycin are also reasonable alternatives. In vitro susceptibility data suggest that oxacillin, dicloxacillin, cephalexin, metronidazole, and the aminoglycosides should be avoided.

Prevention & Control

Currently, there are no recommended prevention and control measures. However, because of the association between intrauterine device (IUD) use and pelvic actinomycosis, women should consider alternative forms of contraception.