Essentials of Diagnosis

- Contact with infected animals, carcasses, hair, wool, or hides from goats, sheep, cattle, swine, horses, buffalo, or deer.

- Incubation period lasting 1-7 days, usually 2-5 days, after exposure.

- Painless lesion progressing to papule, to vesicle, to necrosis, and to eschar.

- Rapid development of chest pain, dyspnea, and circulatory collapse after brief flulike syndrome.

- Direct gram-stained smear and/or cultures of lesions or discharges.

- Widened mediastinum on chest radiograph in inhalational disease.

General Considerations

Anthrax is primarily a disease of herbivores, but humans acquire the disease through contact with infected animals or animal products.

Epidemiology

Historically, anthrax has been an occupational disease of persons who handle animal hair, skin, and other contaminated products. The incidence of this disease in the United States has fallen dramatically; only six cases of anthrax were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 1978 through 1998.

The cutaneous form of the disease is most common. Continued concern about this disease stems from the unfortunate development of anthrax spores as biological weapons by a number of nations.

Microbiology

Bacillus anthracis, a sporulating gram-positive rod, is the causative agent of anthrax.

B anthracis is distinguished from other Bacillus species in the laboratory based on its colony morphology and capsule.

Pathogenesis

B anthracis persists in soil as a nonreplicating spore. These spores are highly resistant to temperature extremes, drying, UV light, high pH, high salinity levels, and routine methods of disinfection. The virulence of B anthracis is due to the presence of a polysaccharide capsule that prevents phagocytosis and to the production of 2 two-component exotoxins. Each of these toxins is of an A-B structure. They share the same B component, known as protective antigen, which binds each of these binary toxins to host cells and mediates internalization. Lethal toxin causes rapid cell death by the action of its A subunit, a zinc metalloprotease that cleaves a critical intracellular signaling molecule. Edema toxin contains an A subunit that acts as a calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase and catalyzes production of cyclic AMP within host cells. This toxin is believed to be responsible for the dramatic tissue edema that characterizes cutaneous anthrax.

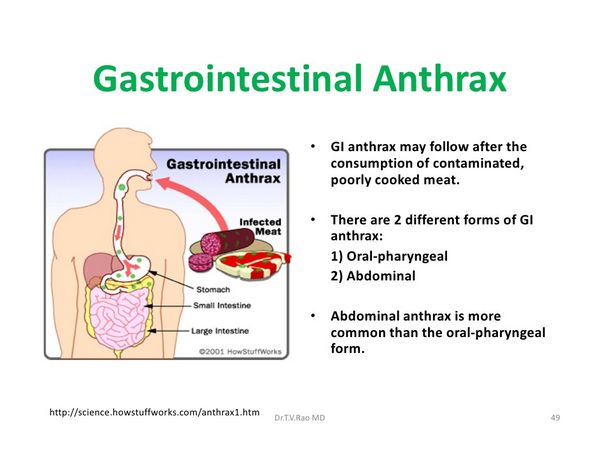

The genes encoding the three toxin components are located on one plasmid, and the genes encoding the capsule are on a second plasmid. Strains missing either of these plasmids are avirulent. Expression of these toxins takes place upon germination of spores within macrophages and vegetative growth of the bacilli, after they have been inoculated into an animal host. Subcutaneous inoculation occurs via abrasions or breaks in the skin, and it leads to cutaneous disease with occasional systemic dissemination. Inhaled spores are deposited in the alveoli, phagocytosed by macrophages, and taken to regional lymph nodes where bacterial growth and disease first become manifest. Gastrointestinal anthrax results from ingestion of grossly contaminated or undercooked meat, and it is extremely rare. Only the spore is infectious for humans; hence, human-to-human transmission of disease does not occur.

Clinical Findings

There are three forms of the disease in humans: cutaneous, inhalational, and gastrointestinal (Box 4).

Cutaneous Anthrax

Cutaneous disease accounts for > 95% of all cases of anthrax. This disease begins as a small, painless, but often pruritic papule. As the papule enlarges, it becomes vesicular and, within 2 days, ulcerates to form a distinctive black (hence the name of the disease) eschar, with surrounding edema. Gram stain of the vesicular fluid may reveal gram-positive rods and rare polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

Inhalational Anthrax

Inhalational anthrax is much less frequent and accounts for < 5% of cases; the incubation period is ~ 10 days, but it may be more prolonged in some cases.

This form of the disease begins with an upper-respiratory flulike syndrome, and after a few days it takes a fulminant course, manifested by dyspnea, cough and chills, and a high-grade bacteremia. Inhalational anthrax is not a disease of the lung parenchyma, but is rather a hemorrhagic mediastinitis. Nearly all patients with this disease die within several days.

Gastrointestinal Anthrax

Gastrointestinal disease is accompanied by mucosal ulceration, mesenteric adenitis, and ascites; it is reported in Africa and Asia but has not been described in the United States.

Diagnosis

An appropriate epidemiologic history involving animal exposure is the cornerstone of the diagnosis of cutaneous anthrax. Other diagnostic features include edema out of proportion to the size of the skin lesion, the lack of pain during the initial phases of the infection, and the rarity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes on Gram stain. The organism can be readily cultivated and forms nonhemolytic gray-white colonies. A critical diagnostic feature of inhalational anthrax is a widened mediastinum on chest radiography. Patients with this disease usually die before organism growth in blood cultures is detected; however, organisms can sometimes be detected in blood with the Gram stain, owing to the high burden of bacteria in the endovascular compartment.

Treatment

Cutaneous anthrax responds well to penicillin G, which should be continued for 7-10 days. Doxycycline is also effective for cutaneous disease. Other antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol, are alternative drugs for penicillin-allergic patients. The addition of streptomycin to penicillin may offer additional benefit.

Penicillin resistance has been reported among some naturally occurring isolates; these strains have remained sensitive to ciprofloxacin. Despite the early use of antibiotics, cutaneous lesions continue to progress through the eschar phase. Surgery or excision of lesions is contraindicated. With appropriate antibiotic therapy, fatalities are rare (< 1%).

Despite the use of antibiotics as described above, inhalational anthrax is almost always fatal, once it becomes clinically manifest. If anthrax is suspected, public health authorities should be notified immediately.

Prevention

Doxycycline or ciprofloxacin (Box 6) may prevent development of inhalational disease if given to exposed individuals before onset of disease. Either of these antibiotics should be given for at least 6 weeks before or 2 weeks after the third dose of anthrax vaccine. The currently licensed anthrax vaccine contains protective antigen, and it has been shown to be effective in limited studies against inhalational disease in monkeys and cutaneous disease in humans.