BRUCELLOSIS

Essentials of Diagnosis

- Suspected in patients with chronic fever of unknown etiology who have a history of occupational exposure or come from a high prevalence area.

- Leukopenia.

- Blood culture or bone marrow cultures on appropriate media.

- Serum antibody titer = 1:160.

- Polymerase chain reaction.

General Considerations

Brucellosis (also called undulant fever, Mediterranean fever, Malta fever) is an infection that causes abortion in domestic animals. It is caused by one of six species of Brucella coccobacilli. It may occasionally be transmitted to humans, in whom the disease could be acute or chronic with ongoing fever and constitutional symptoms without localized findings.

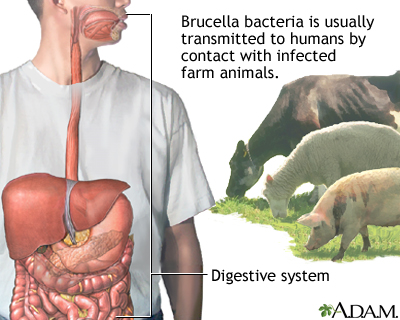

Epidemiology

Brucellosis is transmitted to humans by either direct contact with infected cattle, goat, or sheep (eg, through milk, urine, and products of pregnancy) or indirectly by ingesting contaminated animal products (eg, unpasteurized dairy products). Human-to-human transmission does not occur. The natural reservoir of brucellosis in the United States is domestic animals, especially cattle, bison, sheep, goats, and swine.

The disease exists worldwide, mainly in the Mediterranean basin, the Arabian peninsula, the Indian subcontinent, Mexico, and Central and South America. In the United States, the incidence of brucellosis fell from 4.5 cases/100,000 population annually in the late 1940s to < 0.5 cases/100,000 by the 1990s.

Most reported cases in the United States are due to ingestion of unpasteurized goat milk product imported from Mexico or to occupational exposure involving meat-packing plant employees, veterinarians, laboratory personnel, farmers, and ranchers.

Recently, bison herds in the Rocky Mountain plains of the United States have become infected with brucellae and could potentially infect domestic cattle in the United States.

Microbiology

Sir David Bruce, a British microbiologist, isolated the microorganisms responsible for brucellosis in 1886. Brucellae are nonspore-forming, noncapsulated, small gram-negative coccobacilli. They grow best aerobically in high-peptone media at 37 °C and at pH 6.7. Incubation time could take = 30 days for visible growth on solid media. Colonies are small, smooth, translucent, and amber colored. Of the six known Brucella species, only four are reported to cause human disease: B abortus (cattle), B melitensis (goats), B suis (pigs), and B canis (dogs). Brucellae may be distinguished from each other by their requirements for carbon monoxide atmosphere for growth, growth in the presence of dyes, production of hydrogen sulfide and urease, and specific agglutination in antisera.

Pathogenesis

Routes of infection include ingestion of the contaminated food or dairy products by way of the gastrointestinal tract, direct inoculation through skin cuts or mucus membrane contact, or inhalation of the organisms via the respiratory tract. Subsequently, the microorganisms enter the lymphatics and replicate intracellularly in the regional lymph nodes and from there disseminate hematogenously and localize in the reticuloendothelial system (ie, spleen, liver, other lymph nodes, and bone marrow).

The bacilli multiply intracellularly within the phagocytic cell where they may be killed rapidly, or the organisms may replicate and destroy the phagocytic cell. This results in proliferation within the reticuloendothelial system and the formation of noncaseating granulomas in affected tissue. In most instances, the granulomas undergo a process of healing, with fibrosis, death of the organisms, and frequently calcification.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

After a 2- to 8-week incubation period, affected patients present with a spectrum of disease that varies from an asymptomatic form to a severe illness with bacteremia. Affected patients typically present with fever, sweats, headaches, malaise, and weight loss. If undiagnosed, these symptoms may persist for months to a year. When symptoms last for more than 12 months without any localization, the disease is classified as chronic.

Physical examination, though normal in most cases, may reveal bilateral diffuse lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly in 20%-30% of patients. In the localized form, the infection may affect virtually any organ system. The osteoarticular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and cardiovascular are among the more common affected systems. These forms have signs and symptoms related to the affected organ system.

An infectious discitis with adjacent vertebral bony osteomyelitis typically in the lumbar area, is the most common manifestation of localized osteoarticular disease. Sacroilitis is also characteristic of the musculoskeletal form of the infection. Infective endocarditis occurs in < 2% of brucellosis cases. Patients with chronic brucellosis may have long periods of no symptoms followed by the intermittent recurrence of fever, chills, myalgias, and nonspecific symptoms. This form of relapsing brucellosis may persist for decades and is often refractory to antimicrobial therapy and is frequently associated with multiple or large calcific lesions in the liver and spleen. Many other common illnesses can mimic the most common clinical presentation of brucellosis.

Laboratory Findings

Patients typically have a mild anemia, neutropenia, and rarely thrombocytopenia. The diagnosis of brucellosis is made with certainty when Brucella spp. are recovered from cultures of the blood, bone marrow, or other site. Bone marrow cultures are more often positive than are blood cultures. Blood cultures are often negative in chronic or localized forms. The standard Brucella serum agglutination test is the most widely used serologic test for the diagnosis of Brucella.

The antibodies measured are directed against the lipopolysaccharide. A titer of at least 1:160 is representative of a past or present infection. A fourfold increase or decrease over a 2- to 4-week period represents acute infection. The current serum agglutination test does not detect antibodies directed against Brucella canis, and diagnosis requires a special serologic test or a positive culture.

After successful therapy, the antibody titer may become negative in approximately a year but may remain positive in low titer throughout the patient’s life. Persistence of an elevated titer indicates ongoing infection. The prozone phenomena could lead to a false negative test. Polymerase chain reaction may be used for diagnosis. Primers are directed at different sites of the genomic bacterial DNA. The specificity and sensitivity of this technique may provide a valuable tool for the diagnosis of brucellosis; however, the test is not widely available.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis is one of a fever of unknown origin and includes typhoid fever, infectious mononucleosis, Q-fever, hepatitis, and a host of noninfectious syndromes including lymphoma and systemic lupus erythematosus. Infection with Vibrio cholerae, Francisella tularensis, or Yersinia enterocolitica may give a falsely elevated serum agglutination test since antigen of these microorganisms can cross-react with antigen of Brucella spp.

Treatment

Several antimicrobial agents are active against Brucella spp. (Box 60-2). Combination therapy of two or more active antimicrobial agents is superior to monotherapy as evidenced by a reduction in relapse rates. Antimicrobial therapy shortens the duration of symptoms and reduces the incidence of complications. Tetracyclines are considered the cornerstone of therapy. Several possible combinations have been used: The World Health Organization recommends a 6-week combination regimen of doxycycline and rifampin. Doxycycline and streptomycin are considered equally efficacious. The optimum therapy for endocarditis is unclear. Most patients will require a prolonged period (6 months) of combination antimicrobial therapy, and valvular replacement surgery is often necessary. Although rare, infective endocarditis represents 80% of human brucellosis-related deaths.

Prognosis

With appropriate antimicrobial therapy, the mortality rate of brucellosis is < 1%, although the mortality rate is 3%-5% in untreated cases. It appears that the humoral antibodies play a role in the protection against subsequent infection. Thus patients with brucellosis might be less susceptible to acquire a new infection.

Prevention & Control

The prevention of brucellosis requires the eradication or the control of the infection in animals (Box 3). The use of Brucella vaccines (B abortus strain 19, B melitensis strain Rev-1) has resulted in the elimination of the disease in some animals. The use of effective barriers such as gloves, masks, and goggles can protect individuals at risk from potentially infected animals. Pasteurization of milk will effectively kill Brucella spp. in dairy products.

HACEK INFECTION

Essentials of Diagnosis

- Suspected in patients with periodontal disease with signs and symptoms suggestive of infective endocarditis.

- Large valvular heart vegetation on echocardiography.

- Small, pleomorphic gram-negative coccobacilli that grow best in enriched media and increased CO2 tension.

General Considerations

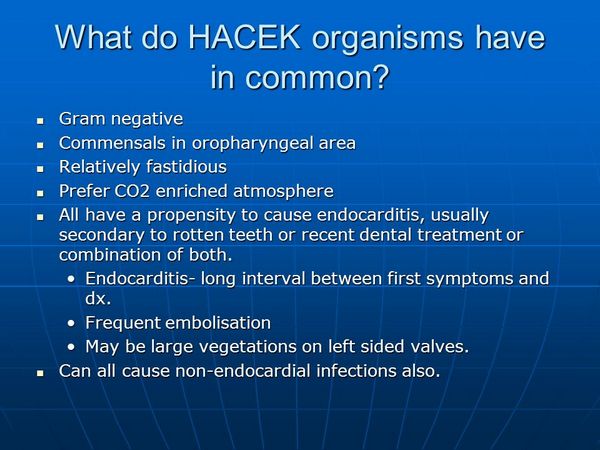

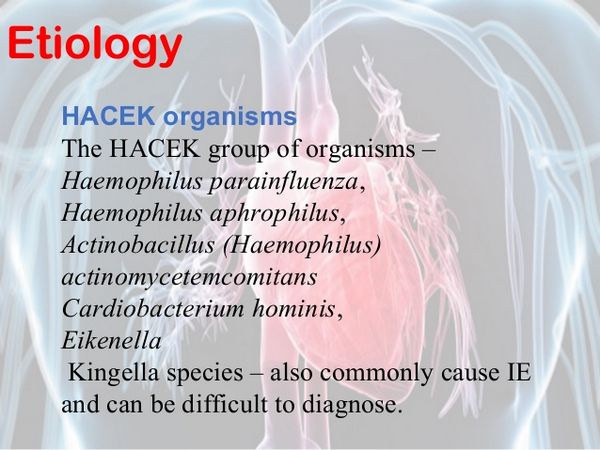

The fastidious bacteria of the HACEK group include Haemophilus aphrophilus and H paraphrophilus, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, and Kingella kingae. These organisms may be considered part of the normal flora of the upper respiratory tract. Because they share common clinical and microbiological properties, they will be reviewed together.

All HACEK microorganisms produce a similar clinical syndrome including infective endocarditis, periodontal disease, and bacteremia (Box 16). Rarely, these microorganisms may cause brain abscess, meningitis, pneumonia, intra-abdominal infections, gynecologic infections, arthritis, osteomyelitis, and human bite wound infection (E corrodens).

Epidemiology

The most common infectious disease caused by these microorganisms is infective endocarditis. These microorganisms account for 3% of infective endocarditis cases. The incidence of HACEK endocarditis is ~ 0.32/100,000 person years of life. HACEK microorganisms are part of the usual microflora of the oral cavity, and this serves as the portal of entry for bacteremia, which may result in infective endocarditis or, very rarely, infections in other organ systems.

Microbiology

Microorganisms of the HACEK group are small, pleomorphic gram-negative coccobacilli that grow best in enriched media (such as sheep blood agar or chocolate agar) and increased CO2 tension. Cultures often require prolonged incubation times (average 5-7 days) for growth. They are distinguished among each other by their biochemical reactions.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

The presentation of endocarditis is often insidious in onset and includes fever, splenomegaly, embolic phenomena, and a new or changing cardiac murmur. More than half of patients with endocarditis will have had a dental procedure within the 6 months before onset of symptoms or poor dentition at the time of diagnosis. Valvular or congenital structural heart disease or the presence of a prosthetic heart valve was present in 60% and 27% of cases, respectively. Cardiac valvular vegetation observed by echocardiography is characteristically large. This finding probably reflects the chronicity of infection before diagnosis. Signs and symptoms of other HACEK infections are related to the affected site of infection.

Laboratory Findings

The diagnosis of HACEK infections requires the cultivation of the bacteria from sterile sites. Biological specimens need to be incubated in enriched media under increased CO2 tension for 5-7 days. C. Imaging. Echocardiography can reveal large endocardial or valvular vegetation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes infective endocarditis caused by other microorganisms, such as staphylococci, enterococci, and fungi.

Treatment

With the emergence of ß-lactamase-producing HACEK organisms, third-generation cephalosporins (eg, cefotaxime or ceftriaxone) are now considered the treatment of choice (see Box 17). The treatment of infections other than infective endocarditis caused by HACEK organisms requires the same antimicrobial therapy used in infective endocarditis; however, the length of therapy might be shorter, depending on the site of infection.

With susceptible microorganisms, combination therapy using penicillin or ampicillin and aminoglycoside is satisfactory. The American Heart Association recommends that native valve and prosthetic valve endocarditis be treated for 4 and 6 weeks, respectively.

Prognosis

Native or prosthetic valve endocarditis caused by HACEK organisms may be cured in 82%-87% of the cases by medical or medical and surgical therapies.

Prevention & Control

Follow American Heart Association guidelines for prevention of infective endocarditis, after dental and other procedures in patients at high risk. See site for cardiovascular-intravascular infection guidelines for subacute bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis.