LISTERIA MONOCYTOGENES

Essentials of Diagnosis

- Incriminated foods include unpasteurized milk, soft cheeses, undercooked poultry, and unwashed raw vegetables.

- Asymptomatic fecal and vaginal carriage can result in sporadic neonatal disease from transplacental and ascending routes of infection.

- Incubation period for foodborne transmission is 21 days.

- Organism causes disease especially in neonates, pregnant women, immunocompromised hosts, and elderly.

- Organism is grown from blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), meconium, gastric washings, placenta, amniotic fluid, and other infected sites.

General Considerations

Epidemiology

L monocytogenes is found in soil, fertilizer, sewage, and stream water; on plants; and in the intestinal tracts of many mammals. It is a foodborne pathogen that causes bacteremic illness and meningoencephalitis, with few if any gastrointestinal manifestations. Contaminated food appears to be the most common source for both sporadic and outbreak-related cases. An estimated 2500 cases occur each year in the United States. The median incubation period for foodborne transmission is ~ 30 days. Foods that have been linked to outbreaks of listeriosis include Mexican style cheeses, unpasteurized milk, and undercooked chicken.

The organisms can multiply at 4°C; therefore, foods refrigerated for prolonged periods are well-recognized sources for microbial transmission. Although the incidence of listeriosis is relatively low, there are several populations at increased risk for disease. These populations include persons older than 70 years, pregnant women, and patients with defects in cell-mediated immunity, including transplant hosts, those receiving high-dose corticosteroids, and patients with AIDS. The case fatality rate associated with listeriosis is ~ 23%; listeriosis is estimated to account for almost one-third of all food-related disease deaths. Asymptomatic vaginal and fecal carriage in pregnant women can result in sporadic neonatal disease, either from transplacental infection or from exposure during delivery.

Microbiology

L monocytogenes is a facultative anaerobic, non-spore-forming, gram-positive bacillus that can grow in acidic conditions, high salt concentrations, and a wide temperature range, including the temperatures of household refrigerators. There are = 13 serotypes of L monocytogenes, of which types 1B and 4B are the most commonly associated with disease.

Pathogenesis

L monocytogenes displays unusual capabilities in its interactions with host cells and its mechanisms of pathogenesis. After entering the small intestine, the organisms induce their uptake into epithelial cells and macrophages. E-cadherin serves as a host cell receptor. Once internalized, the bacteria rupture the phagolysosomal vacuolar membrane, using a pore-forming hemolysin, listeriolysin O, and escape into the host cell cytoplasm. Listeria multiplies readily within this environment; it also moves about the cytoplasm by nucleating host cell actin polymerization at one pole of the bacterial cell, using its protein ActA. An actin “comet tail” is formed as actin regulatory proteins are recruited, and the process extends. The actin tail itself is fixed, and the bacteria are propelled by polymerization at the proximal end of the tail at speeds of ~ 0.1 um/s. Many of the bacteria migrate to the periphery of the cytoplasm, pushing against the host cell outer membrane to form elongated protrusions. These protrusions are then ingested by adjacent cells; Listeria bacteria then secrete phospholipases and listeriolysin O that rupture the double membrane that separates them from this second cell’s cytoplasm. This mechanism allows Listeria spp. to spread from cell to cell without directly contacting the extracellular environment. Several other pathogens induce actin polymerization as a means of movement within the host cell cytoplasm, including Shigella spp., Rickettsia spp., and vaccinia virus.

Clinical Findings

Central Nervous System (CNS) Infection

Although most cases of listeriosis occur after ingestion of contaminated food, few patients complain of gastrointestinal symptoms or display gastrointestinal signs. The CNS is the site most commonly involved, where disease results in three different clinical presentations: meningitis, meningoencephalitis, and rhomboencephalitis. Meningitis is the most common manifestation of listeriosis in adults and children. L monocytogenes, after Escherichia coli and the group B streptococci, is the third most common cause of bacterial meningitis in adults and neonates, and it accounts for 5-15% of cases. The clinical manifestations of Listeria meningitis are similar to other forms of bacterial meningitis; however, the proportion of neutrophils among CSF leukocytes is often lower, and Gram stains of CSF are usually negative. In some cases, meningitis is accompanied by clinical signs of encephalitis. This organism, unlike other bacterial causes of meningitis, exhibits a tropism for brain parenchyma and, in particular, the brain stem, resulting in rhomboencephalitis. The latter is often preceded by 4-10 days of nonspecific flulike symptoms, followed by cranial nerve deficits, particularly of the sixth and seventh nerves. Brain stem involvement may lead to hemiparesis, ataxia, and even respiratory compromise. In most cases of meningoencephalitis, the CSF monocyte differential counts may reach 80-90%, but cases with no pleocytosis and normal CSF protein and glucose levels have been reported. Brain abscess is a rare manifestation of CNS listeriosis.

Bacteremia

Bacteremia or non-CNS focal infection occurs in 5-30% of adult cases. The diagnosis is based on positive blood cultures. Listeria causes focal infections in bone, native and prosthetic joints, eyes, spinal cord, pleura, peritoneum, and liver. Endocarditis, myocarditis, and mycotic aneurysms have also been described. Approximately one-third of women who contract Listeria infection are pregnant. Women in their third trimester are at greatest risk, but symptoms are usually mild, often mimicking a flulike illness. Blood cultures, if obtained, may be positive, but symptoms usually resolve spontaneously without therapy.

Neonatal Infection

Neonatal Listeria infection may present as an amnionitis, and infection is associated with premature labor. An uncommon clinical syndrome called granulomatosis infantiseptica has been described. This syndrome is caused by dissemination of L monocytogenes in utero. Abscesses and granulomata form within the fetal liver, lung, spleen, kidneys, brain, and skin. The mortality rate is high, ranging from 35% to 55%.

Diagnosis

L monocytogenes can be easily cultivated in the microbiology laboratory from blood, CSF, meconium, gastric washings, placenta, amniotic fluid, and other specimens. A CSF Gram stain with gram-positive or-variable rods should suggest Listeria infection, but this organism may be mistaken as a diphtheroid.

Treatment

There are no clinical trials comparing different antibiotic regimens for the treatment of listeriosis. Ampicillin or penicillin is generally recommended as the treatment of choice (Box 2). Gentamicin is added for severe infections, because the combination of ampicillin and an aminoglycoside is more effective than ampicillin alone in animal models. These agents should be given intravenously. The duration of therapy required to prevent relapse is not known; however, 10-14 days is recommended in patients without meningitis, 2-3 weeks is recommended for those with meningitis, and 3-6 weeks is recommended for immunosuppressed patients. Another effective agent is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, because high intracellular levels are achieved, and it is bactericidal for Listeria species.

Prognosis

Listeria infection of the CNS is associated with a high mortality rate. Of patients with meningoencephalitis, 36-51% die. Most of those who survive have persistent neurologic sequelae. Early recognition and rapid institution of antibiotics are critical for improving outcome.

Prevention

Patients at risk for listeriosis should be advised on how to minimize their exposure to this organism (Box 3). This advice should include cooking well all food from animal sources, washing raw vegetables thoroughly, and keeping uncooked meat separated from vegetables and cooked foods. Patients should also avoid consumption of unpasteurized milk, soft cheeses, or foods made with raw milk, and they should wash hands, knives, and cutting boards after handling uncooked food. An additional recommendation for high-risk persons is to heat all leftovers or ready-to-eat foods until these foods are steaming hot.

CORYNEBACTERIUM JEIKEIUM

Infection with Corynebacterium jeikeium, formerly known as Corynebacterium CDC group JK, almost invariably occurs in a hospital setting, because these bacteria commonly colonize the skin of hospitalized patients. Patients at highest risk for colonization include those receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics and those with neutropenia. The most common form of disease is bacteremia and is most often seen in neutropenic patients after breaks in the integument of their skin, such as with intravascular catheters.

Endocarditis with this organism has been described, but it is rare, as are extravascular infections such as pneumonia, peritonitis, and prosthetic knee infections. The treatment of choice is vancomycin (1 g every 12 h); the length of therapy is dictated by the disease process. Prosthetic valve endocarditis with C jeikeium often requires removal of the valve for control of the infection.

OTHER CORYNEBACTERIUM SPECIES

Corynebacterium species colonize the skin and are therefore frequently recovered as contaminants in blood cultures; however, serious infections can occur. In particular, immunocompromised hosts and those with indwelling vascular catheters have an increased risk of infection with these organisms. C ulcerans, C pseudotuberculosis, C bovis, C striatum, and C pseudodiphtheriticum rarely cause human disease, but severe upper respiratory tract, cardiac, and CNS diseases have been reported. Rhodococcus equi (previously C equi) has recently been reported to cause pneumonia and cavitary pulmonary disease in patients with AIDS and renal transplantation. The treatment of choice for this organism is erythromycin or imipenem-cilastatin, plus rifampin.

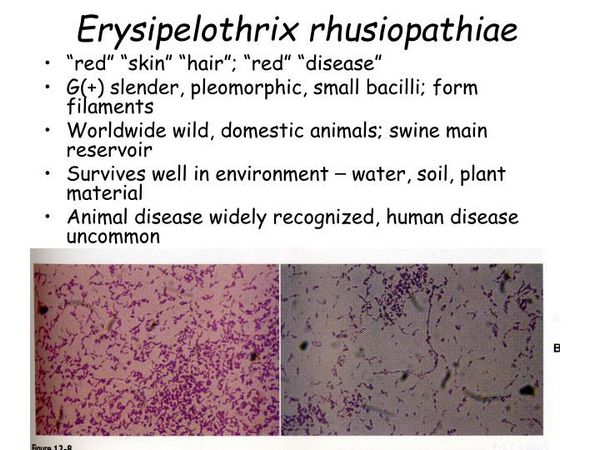

ERYSIPELOTHRIX RHUSIOPATHIAE

General Considerations

Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae is a gram-positive bacillus that causes occupationally related skin infections and, rarely, septicemia in humans.

Epidemiology

E rhusiopathiae is ubiquitous in nature and is an uncommon cause of human disease. It can infect mammals, birds, fish, shellfish, and insects, and it may reside in swine, which serve as a reservoir. Disease in humans is most commonly seen in persons with an appropriate exposure, usually including butchers, slaughterhouse workers, and especially fish handlers. Most cases of skin infection (“erysipeloid”) occur in the summer and early fall. The organism is often traumatically inoculated and intense inflammation of the dermis follows.

Microbiology and Pathogenesis

The organism is non-spore forming and nonmotile and is a facultative anaerobe. The organism may appear as a beaded gram-positive rod owing to partial decolorization during the staining process. It grows well on sheep blood agar and exhibits alpha hemolysis. The organism tolerates a high-salt environment and can survive in saltwater. E rhusiopathiae is catalase negative, oxidase negative, and weakly fermentative.

Clinical Findings

Skin lesions are usually purplish-red with a sharply defined, raised, serpiginous border; they most commonly involve the proximal region of the hands and fingers. Lesions spread slowly, and, over time, the central portion heals leaving a pale center with a surrounding purplish-red border. Proximal lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms are rare. Acute or subacute endocarditis secondary to E rhusiopathiae is uncommon, but is severe when it occurs. The aortic valve is most commonly involved, and 40% of patients will have or just had the characteristic skin lesion of erysipeloid.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis requires an appropriate epidemiologic history. The skin lesion may resemble erysipelas caused by Streptococcus pyogenes, but the rate of progression is slower, and there is a lack of lymphangitis, lymphadenopathy, and systemic symptoms. Full-thickness skin biopsy with appropriate culture will yield the organism in the majority of cases. Blood cultures should also be obtained.

Treatment

Treatment of choice for E rhusiopathiae infection is penicillin. Erysipeloid is usually self-limited and resolves over the course of 3 weeks, but therapy will hasten the resolution of symptoms. Endocarditis should be treated with intravenous penicillin at 12-20 million U/day, in 4-6 divided doses for 4-6 weeks. It is noteworthy that E rhusiopathiae is resistant to vancomycin. Despite appropriate therapy, the mortality rate for patients with E rhusiopathiae endocarditis is 30-40%.

BOX 1. Listeriosis in Children and Adults

Children

Adults

More Common

- Neonatal disease

Early onset: pneumonia, septicemia

Late onset: meningitis

- Asymptomatic carriage

- Influenzalike illness

Less Common

- Granulomatosis infantisepticam

- Amnionitis

- Bacteremia and/or meningitis in patients with decreased cell-mediated immunity

BOX 2. Treatment of Listeriosis

Children

Adults

First Choice

- Penicillin G, 300,000 U/kg/d in 6 divided doses

- Ampicillin, 200 mg/kg/d in 6 divided doses

Second Choice

- Trimethoprim, 20 mg/kg/d, plus sulfamethoxazole, 100 mg/kg/d in 4 divided doses

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as per children

Penicillin Allergic

- Trimethoprim, 20 mg/kg/d, plus sulfamethoxazole, 100 mg/kg/d in 4 divided doses

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as per children

BOX 3. Control of Listeriosis

Prophylactic Measures

- Therapy of infection diagnosed during pregnancy may prevent vertical transmission

- Avoid contact between untreated manure from herds of cattle or sheep and foods for human consumption

- Pregnant women and immunosuppressed patients should avoid unpasteurized dairy products, soft cheeses, undercooked meats, and raw unwashed vegetables

Isolation Precautions

- Standard precautions, but cases should be reported to the regional health department for recognition and control of common source outbreaks

BOX 4. Anthrax Syndromes in Children and Adults

More Common

- Cutaneous disease accounts for 95% of cases

Less Common

- Spectrum of disease includes inhalational, gastrointestinal, and meningeal

BOX 5. Treatment of Anthrax

Children

Adults

First Choice

- Penicillin G, 250,000-400,000 U/kg/d in 4-6 doses IV; consider addition of streptomycin

- Penicillin G, 16-24 million U/d IV divided every 4-6 h; consider addition of streptomycin

Second Choice

- Ciprofloxacin, 20-30 mg/kg/d IV in 2 doses

OR

- Doxycycline, 2-4 mg/kg/d IV in 2 doses

OR

- Chloramphenicol, 12-25 mg/kg/d IV in 4 doses

- Ciprofloxacin, 800 mg/d IV in 2 doses

- Doxycycline, 200 mg/d IV in 2 doses

OR

- Chloramphenicol, 50 mg/kg/d IV in 4 doses

Pediatric Considerations

- Doxycycline should not be given to children < 8 y old, and ciprofloxacin should not be given to children in general, unless disease is life-threatening

Penicillin Allergic

- Doxycycline (dosage as above)

- Ciprofloxacin (dosage as above)

BOX 6. Control of Anthrax

Prophylactic Measures

- Doxycycline, 200 mg (2-4 mg/kg in children), OR ciprofloxacin, 1 g (20-30 mg/kg in children) orally per d in 2 divided doses may be used for exposed individuals (neither doxycycline nor ciprofloxacin should be given to children < 8 y old or < 18 y old, respectively, if the likelihood of exposure is high)

- Surveillance and control of industrial and agricultural sources of B anthracis

- Cell-free vaccine is available for those at risk but is not licensed for children or pregnant women

Isolation Precautions

- Standard precautions

- Contaminated dressings or bedclothes should be burned or steam-sterilized to destroy the spores

BOX 7. Diphtheria Syndromes in Children and Adults

More Common

- Membranous nasopharyngitis

- Obstructive laryngotracheitis

- Abrupt onset low-grade fever, malaise

Less Common

- Cutanous

- Vaginal

- Conjunctival

- Otic

- Complications including cardiac and neurologic toxicity

BOX 8. Treatment of Diphtheria

Children

Adults

First Choice

- Antitoxin (available from CDC [phone (404) 639-8200])

Pharyngeal/laryngeal disease ( < 48 h), 20,000-40,000 U IV

Nasopharynx disease, 40,000-60,000 U IV

Extensive disease or > 3 d, 80,000-120,000 U IV

PLUS

Erythromycin, 40-50 mg/kg/d (max, 2 g/d)

- As for children (erythromycin, 2 g/d in 4 doses)

Second Choice

- Penicillin G, 100,000-150,000 U/kg/d divided every 6 h (max 1.2 million U)

OR

- Penicillin aqueous procaine, 25,000-50,000 U/kg/d divided every 12 h (max 1.2 million U)

- As for children (penicillin G, 12 million-20 million U/d divided every 4-6 h)

Penicillin Allergic

- Erythromycin

- Erythromycin

BOX 9. Control of Diphtheria

Prophylactic Measures

- Notify public health officials

- Close contact tracing

- Observe close contacts for 7 d

- Culture close contacts

- Antimicrobial prophylaxis for close contacts:

Oral erythromycin, 40-50 mg/kg/d (children); 2 g/d (adults) × 7 d

Single IM dose benzathine penicillin G, 600,000 U for those < 30 kg or 1.2 million U for those > 30 kg

- Immunization with toxoid vaccine

Primary series

Children 6 wk-7 y, DTaP (3 IM injections at 4- to 8-wk intervals, then a 4th IM dose 6-12 mo after 3rd dose)

Children > 7 y and adults, dT (2 IM injections at 4- to 8-wk intervals, then a 3rd IM dose 6-12 mo after 2nd dose)

Booster

Children receiving primary series < 4 wk, DTaP at school entry, then every 10 y

Children/adults, dT every 10 y

Isolation Precautions

- Droplet precaution isolation until 2 negative nasopharyngeal cultures