Essentials of Diagnosis

- Foul odor of draining purulence

- Presence of gas in tissues

- No organism growth on aerobic culture media

- Infection localized in the proximity of mucosal surface

- Presence of septic thrombophlebitis

- Tissue necrosis and abscess formation

- Association with malignancies (especially intestinal)

- Mixed organism morphologies on Gram stain

General Considerations

Epidemiology and Ecology

Anaerobic bacteria are the predominant component of the normal microbial flora of the human body. The following sites harbor the vast majority of them:

Skin

Mostly gram-positive bacilli such as Propionibacterium acnes

Gastrointestinal tract

In the oral cavity Prevotella spp., Porphyromonas spp., Peptostreptococcus spp., microaerophillic streptococci, and Fusobacterium spp. are the most important anaerobes found; they significantly outnumber aerobic bacteria (1000:1 ratio). On the colonic lumen, Bacteroides fragilis, other Bacteroides spp., clostridia, and the previously mentioned oral flora are by far the predominant colonizing organisms (1000:1 ratio to aerobes) and play a crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance of local microflora as well as in metabolizing bile acids and cholesterol and absorbing vitamin K.

Respiratory tract

Fusobacterium nucleatum, B fragilis, Prevotella melaninogenica, and Peptostreptococcus spp. are the most common anaerobic organisms in this site.

Female genital tract

Lactobacillus spp., the predominant species in this location, protect against bacterial vaginosis.

Exogenous infectious sources

In nature, species of the Clostridium genus are found in decaying vegetation, soil, ocean sediment, and in human and animal gastrointestinal tracts. Tetanus and botulism (caused by the toxins of C tetani and C botulinum) are examples of exogenously acquired anaerobic infections. The facultative gram-negative anaerobic bacillus Capnocytophaga canimorsus is part of the normal oral flora of canine species, but in susceptible hosts such as immunocompromised individuals, it may cause septic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation, an example of an animal-to-human transmission of infection.

Microbiology

Anaerobes are defined as bacteria that cannot grow on the surface of solid media in an atmosphere containing = 18%-20% of oxygen even when this atmosphere is enriched with = 10% of CO2. The degree of oxygen tolerance differs among these microorganisms; a facultative anaerobe is a bacterium that can grow in either the presence or absence of oxygen, and a strict anaerobe is one that requires < 0.5% oxygen to grow on an agar surface. Microaerophilic is a term used for bacteria that grow poorly aerobically but distinctly better under 10% CO2.

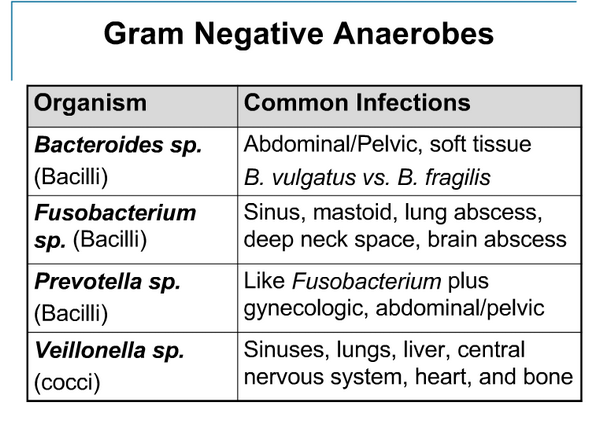

Anaerobic bacterial species are numerous; taxonomic data are sometimes confusing and have undergone recent changes. For the purpose of this chapter, we have focused on the most representative pathogens (Table 1).

Pathogenesis

The pathogenic role of anaerobic bacteria was well established at the beginning of the 1900s. Most infections that involve anaerobes arise from the host’s normal indigenous flora, as these bacteria are widely distributed among humans and other animal species. Organisms that are most important are those present in significant numbers at the sites of infection as well as those with high virulence or greater antimicrobial resistance.

The characteristic pathologic features of anaerobic infections are suppuration, abscess formation, and tissue destruction. Several factors contribute to the survival and spread of these organisms:

Microbial Factors:

- Anaerobic environment causes defective neutrophil killing and microbial growth is slower; therefore antibiotic susceptibility decreases.

- Bacterial enzymes such as collagenase and hyaluronidase promote tissue destruction.

- Organisms such as B fragilis have a polysaccharide capsule that impairs phagocytosis.

- Toxin-mediated effects are important in the pathogenicity of most of the genus Clostridium. This occurs in the form of absorption of preformed toxin such as in cases of botulism or as a result of bacterial overgrowth and toxin production, which is the mechanism of antibiotic-associated C difficile colitis.

- Synergism plays a crucial role in anaerobic pathogenesis, especially in the context of mixed infections because the presence of other aerobic bacteria helps create the optimal environmental conditions for the proliferation and virulence of anaerobes.

Host Factors

Normal anaerobic flora become pathogenic under circumstances in which natural barriers that prevent it from gaining access to sterile sites are disrupted. This might happen by a variety of different mechanisms and depends on the site in which the florae occur.

- In pleuropulmonary infections, the usual precipitating factor is an alteration of the level of alertness that may impair the gag and cough reflexes. General anesthesia, cerebrovascular accidents, a variety of drug overdoses, and alcohol intoxication are examples of situations in which normal oropharyngeal flora gains access to the “sterile” lower respiratory tract; dysphagia, and esophageal or gastric outlet obstruction may also lead to aspiration of large amounts of anaerobes.

- Trauma and tissue ischemia are two important mechanisms that predispose to anaerobic infection: seriously contaminated wounds are an example in which poor blood flow and tissue necrosis provide an ideal environment for C perfringens to grow and produce significant amounts of toxin eventually leading to gas gangrene.

- Systemic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus in which the immune response is impaired and vascular compromise might be present, predispose to soft tissue infections of the lower extremities in which anaerobic organisms are commonly found. The presence of foreign devices in different sites may be associated with certain anaerobic infections. Classically, women with intrauterine devices may develop actinomycosis. Central nervous system shunts can become infected with skin colonizing Propionibacterium spp.

Latrogenic Factors:

- In postsurgical abdominal infections, manipulation of bowel causes translocation of bacteria into the peritoneal cavity: anaerobes are universally present as copathogens in a polymicrobial flora.

- Administration of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents alters the normal colonic flora and allows C difficile to proliferate uninhibited; toxin production by this organism leads to the development of antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis.

Important Anaerobes: Clinical Syndromes

Table 1. Important anaerobic bacteria.

Gram-Positive Bacilli

Gram-Positive Cocci

Gram-Negative Bacilli

Gram-Negative Cocci

Spore forming:

- Clostridium botulinum

- C tetani

- C difficile

- C septicum

- C ramosum

- Microaerophilic streptococci

- Peptococcus niger

- Prevotella melaninogenica

- Peptostreptococcus spp

- B fragilis

- Porphyromona spp

- Prevotella melaninogenica

- Fusobacterium nucleatum

- F necrophorum

- Veillonella spp.

Nonspore forming:

- Propionibacterium spp.

- Lactobacillus spp.

- Bifidobacterium spp.

- Actinomyces spp.

Table 2. Tetanus immunization.

Active Immunization

- DTP (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus): Recommended doses (IM) should be given at 2, 4, 6, and 15-18 mo, and at 4-6 years of age.

- DT (diphtheria, tetanus): Recommended for patients above 7 years old; 2 doses (IM) 4-8 weeks apart and a third dose 6-12 mo later confer immunity for at least 5 years; boosters should be given to all patients every 10 years and more frequently if high-risk activities have occurred

Passive Immunization

Human tetanus immunoglobulin (500 IU IM) may shorten the duration and lessen the severity of tetanus cases; should be administered prophylactically to patients not immunized during the previous 5 years who have a tetanus-prone wound or if immunodeficiency is suspected; active immunization should also be initiated at the time the immunoglobulin is given

BOX 1. Infections Frequently Associated with Anaerobic Bacteri

Site

Clinical Syndrome

Anaerobe Involved

Head & Neck

- Chronic sinusitis

- Chronic otitis media/mastoiditis

- Odontogenic infections

- Periodontal infections

- Peritonsillar abscess

- Neck space infections

- Bacteroides fragilis group

- Porphyromonas spp.

- Prevotella spp.

- Peptostreptococcus spp.

- Fusobacterium spp.

- Necrophorum spp.

Central Nervous System

- Brain abscess

- Subdural empyema

- Epidural abscess

- B fragilis group

- Peptostreptococcus spp.

- Fusobacterium spp.

- Prevotella spp.

- Actinomyces spp.

- Microaerophilic streptococcus

Respiratory Tract

- Aspiration pneumonitis

- Empyema

- B fragilis group

- Prevotella melaninogenica

- Bacteroides spp.

- Peptostreptococcus spp.

- Fusobacterium spp.

- Clostridia

- Veillonella spp.

- Intra-abdominal

- Peritonitis

- Intra-abdominal abscess

- Appendicitis

- Pyogenic liver abscess

- Postsurgical wound infections

- Enteritis necroticans

- Neutropenic enterocolitis

- Bacteroides spp.

- Peptostreptococcus spp.

- Fusobacterium spp.

- Lactobacillus spp.

- Eubacterium spp.

- Clostridia

Female Genital Tract

- Endometritis

- Amnionitis

- Septic abortion

- Postsurgical wound infections

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- IUD-related bacterial vaginosis

- Peptostreptococcus spp.

- Prevotella spp.

- Porphyromonas spp.

- Clostridia

- Actinomyces spp.

- Eubacterum nodatum

Skin, Soft Tissue, and Bone Infections

- Bite wound infections

- Diabetic foot infections

- Infected decubitus ulcers

- Burn wound infections

- Paronychia

- Breast abscess

- Infected sebaceous and pilonidal cysts

- Anaerobic cellulitis

- Necrotizing fasciitis

- Myonecrosis (gas gangrene)

- Chronic osteomyelitis

- B fragilis group

- Fusobacterium spp.

- Prevotella spp.

- Porphyromonas spp.

- Clostridia

- Peptostreptococcus spp.

Toxin-Mediated Clostridial Diseases

- Botulism

- Tetanus

- Antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis

- Clostridium botulinium

- C tetani

- C difficile

BOX 2. Treatment of Infections Caused by Anaerobes

Group

First Choice

Alternatives

Comments

Anaerobic Gram-Negative Bacilli

Metronidazole, 500 mg IV every 6 h

Clindamycin, 900 mg IV every 8 h

Fusobacterium spp. sensitive to penicillin G; carbapenems2 or ß-lactam-ß-lactamase inhibitor combinations3 also effective

Anaerobic Gram-Negative Cocci (Veillonella spp.)

Penicillin G, 10-24 million U IV, continuous infusion or every 4-6 h interval dosing

Clindamycin, 900 mg IV every 8 h

Metronidazole activity unpredictable; not recommended for treatment

Anaerobic Gram-Positive Nonspore-Forming Bacilli

Penicillin G, 10-24 million U IV, continuous infusion or every 4-6 h interval dosing

Clindamycin, 900 mg IV every 8 h

Widespread resistance to metronidazole

Anaerobic Gram-Positive Spore-Forming Bacilli (Clostridium spp.)

Penicillin G, 10-24 million U IV, continuous infusion or every 4-6 h interval dosing

Metronidazole, 500 mg IV every 6 h

In resistant organisms, carba-penems2 or ß-lactam-ß-lactamase inhibitors3 effective

Anaerobic Gram-Positive Cocci

Penicillin G, 10-24 million U IV, continuous infusion or every 4-6 h interval dosing

Clindamycin, 900 mg IV every 8 h

Antibiotic-Associated Colitis

Metronidazole, 250 mg orally three times a day (7-14 days)

Vancomycin, 125 mg orally four times a day (7-10 days)

Stop other antibiotics if possible

1) Combination therapy directed against concomitant aerobic pathogens is of paramount importance in successful treatment of anaerobic infections; other agents used will depend on specific infection sites and resistance patterns of other organisms. All dosing information is for adult patients with normal renal and hepatic functions. Pediatric dosing: penicillin G, 25,000 U/kg/d; metronidazole, 30 mg/kg/d; clindamycin, 25 mg/kg/d (in patients with normal renal and hepatic functions).

2) Imipenem, 500 mg IV every 6 h, or meropenem, 1 g IV every 8 h if resistance to other first-line agents is encountered.

3) Ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, 3.1 g IV every 6 h; piperacillin-tazobactam, 3.375 g IV every 6 h; ampicillin-sulbactam, 1.5-3.0 g IV every 6 h; amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, 500 mg orally every 8 h.

BOX 3. Prevention and Control of Anaerobic Infections

- Thorough cleansing and debridement of wounds

- Avoid contamination of sterile sites with “normal” flora from adjacent structures

- Ensuring good vascular supply to tissues

- Minimize use of broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Prevent aspiration of oropharyngeal contents into lower airways

- Attempt to reduce duration of labor (in the case of obstetrical infections)

- Immunization (see Table 1) and, when appropriate, toxin neutralization