Box 1 summarizes different clinical syndromes associated with anaerobic bacteria. The sections that follow describe the various syndromes, including clinical findings. For some syndromes, specific diagnosis and treatment information is included as well. For other syndromes, see summary diagnosis and treatment sections at the end of the chapter.

HEAD & NECK

EAR & PARANASAL SINUSES

The flora in as many as two-thirds of chronic sinusitis and otitis cases includes B fragilis, Prevotella spp., Peptostreptococcus spp., and Porphyromonas spp. It is not surprising that ~50% of patients with chronic otitis media are infected with anaerobic bacteria, B fragilis being the most common. Mastoiditis may arise as a complication in some of these cases. Clinical findings related to these infections are found in site.

ORAL CAVITY

This site is heavily colonized with anaerobes. Consequently, many infections involving oral cavity structures as well as the pharyngeal spaces involve anaerobic bacteria.

Clinical Findings

Odontogenic infections including endodontal processes and periapical and dental abscesses may become more serious by spreading to the perimandibular space; here they present with pain and swelling and require surgical intervention. Gingivitis, pyorrhea, and periodontitis involve anaerobes as well; an extreme of this type of process is necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (Vincent’s angina or trench mouth), which manifests as severe tissue destruction, pain, and malodorous discharge. AIDS and Down’s syndrome are conditions that predispose to periodontal disease and subsequently to odontogenic infections.

PHARYNGEAL SPACES

Clinical Findings

Ludwig’s angina is a bilateral infection of the sublingual and submandibular spaces that commonly involves anaerobic bacteria and causes swelling of the oral tissues, especially at the base of the tongue, where it may lead to respiratory compromise. It manifests as indurated cellulitis and begins on the mouth. A dental source of infection can be found in 50-90% of cases. Lemiere’s syndrome is a life-threatening complication of Fusobacterium necrophorum infection in the posterior compartment of the lateral pharyngeal space, which consists of suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein often accompanied by bacteremia and metastatic abscesses to the lungs and liver. Surgical intervention is almost always necessary in conjunction with intravenous antibiotics.

Signs and Symptoms

Clinical features of infection of the pharyngeal spaces are dysphagia, hoarseness, nuchal rigidity, fever, and trismus. In Ludwig’s angina, a brawny, boardlike swelling of the submandibular spaces, which does not pit on pressure, is present when the mouth is held open and the tongue is pushed up to the roof of the mouth.

Imaging

Once the diagnosis is made (see below), imaging studies help delineate the extent of the process. Soft tissue x-ray of the neck may show widening of the different pharyngeal spaces involved. Ultrasonography, radionuclide scanning, and computerized tomography (CT) are useful for localizing infections of the head and neck.

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

Oral anaerobes are commonly involved in brain abscesses, occasionally in epidural and subdural empyemas, and very rarely in meningitis. These infections usually arise in the setting of chronic otitis media, sinusitis, or odontogenic processes. Less frequently, brain abscesses can be secondary to hematogenous spread from distant sites in which case they tend to be multiple. Anaerobic infections can also be found as a complication of neurosurgical procedures.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Clinical features are those of a space-occupying lesion, including headache, vomiting, altered mental status, focal neurologic symptoms, and seizures. Fever is present in only half of cases; depending on the location of the lesion, corresponding neurologic deficits can be seen. Funduscopic examination may reveal papilledema.

Laboratory Findings

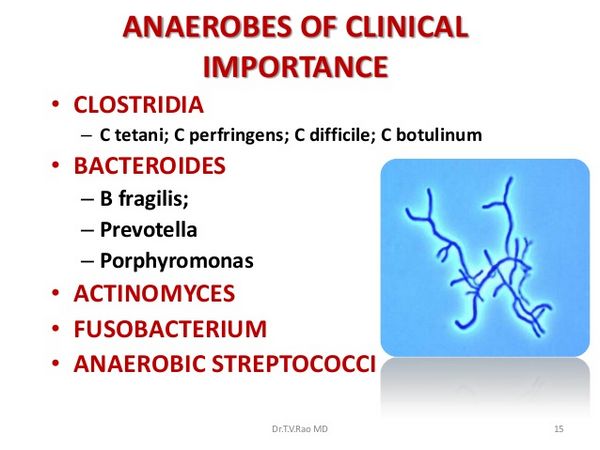

Microbiology findings may include B fragilis, Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium, Prevotella spp., Actinomyces, Propionibacterium, or microaerophilic streptococci in conjunction with aerobic organisms such as staphylococci, streptococci, and gram-negative bacilli.

Invasive procedures such as lumbar puncture should only be performed after careful physical exam to evaluate for increased intracranial pressure or impending herniation. Cerebrospinal fluid examination may show a moderate pleocytosis, high protein concentration, and normal glucose level suggestive of parameningeal inflammatory foci.

Imaging

The diagnosis is confirmed by contrast-enhanced CT or magnetic resonance imaging.

RESPIRATORY TRACT

Aspiration of oral and dental flora results in anaerobic pleuropulmonary infections. Predisposing conditions are alterations in mental status, gingivitis, and periodontal disease.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Pulmonary abscesses of anaerobic origin usually have an indolent subacute or chronic presentation with symptoms such as malaise, weight loss, pleuritic chest pain, and cough that may be accompanied by foul smelling sputum and can be mistaken for malignancy; a febrile response depends on the patient’s age and immune status.

Pathologically, early in the course, pneumonitis is present and then may evolve to form an abscess causing significant tissue destruction. The pleural cavity is frequently involved, and this results in empyema. Commonly affected anatomical sites are dependent regions such as the posterior segments of the upper lobes and the superior segments of the lower lobes.

Laboratory Findings

Organisms of the B fragilis group, other Bacteroides spp., Prevotella melaninogenica, Fusobacterium spp., peptostreptococci, Peptococcus spp., gram-negative bacilli such as Clostridium spp., or occasionally gram-positive cocci of the Veillonella spp. are found. In most cases, aerobic organisms are also present, and successful treatment needs to cover such pathogens as well.

For microbiologic diagnosis, expectorated sputum is not useful as a result of the presence of abundant normal anaerobic flora of the upper airways and oropharyngeal cavities; therefore, invasive procedures including bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage is important in identifying the causative organisms. Empyema fluid should always be inoculated into appropriate anaerobic vials and sent for anaerobic culture.

Imaging

Initial findings on chest x-ray are those of a pneumonic infiltrate. This may evolve to form abscesses in which air-fluid levels can be detected. For optimal delineation of extent of involvement, CT of the chest should be performed.

INTRA-ABDOMINAL

The gastrointestinal tract harbors a rich microbial flora, and any process that involves perforation or manipulation of a hollow viscus could potentially result in the translocation of bacteria into normally sterile sites. In the oral cavity, there are 107-108 anaerobes/mL of oral contents; the proportion is 10-1000/mL in the stomach, 104-106 anaerobes/mL in the terminal ileum, and 1011/g of stool in the colon.

BOWEL

Upper-gastrointestinal-tract processes such as perforated peptic ulcer tend to involve gram-positive anaerobic and aerobic bacteria, whereas lower-tract diseases like appendicitis and colonic perforations are associated with coliforms and anaerobic gram-negative species including B fragilis, Bacteroides spp., and Fusobacterium spp. Therefore, peritonitis (secondary to perforated viscus) and intra-abdominal abscesses always involve anaerobes as a component of a mixed flora. Postsurgical infections may have an anaerobic component as well. See site for clinical findings related to these infections.

Colonic malignancies are commonly associated with members of the Clostridium species — septicum, tertium, and perfringens, all of which may cause bacteremia and gas gangrene of the bowel. Enteritis necroticans (caused by C perfringens) and neutropenic enterocolitis or typhlitis (caused by C septicum) are two representative severe clostridial bowel infections.

LIVER & BILIARY TREE

Biliary tract infections in nonobstructed biliary systems seldom involve anaerobes, but in patients with obstruction caused by tumors, B fragilis or C perfringens can be present. Bacterial liver abscesses are usually polymicrobial, and anaerobes constitute part of the flora.

The diagnosis of hepatic or intra-abdominal anaerobic abscesses is made with imaging studies such as CT. If large abscesses are present, drainage is a component of successful therapy and can be achieved either surgically or in some cases by percutaneous CT or ultrasound-guided techniques. See site for clinical findings related to these infections.

FEMALE GENITAL TRACT

Alteration of the normal microbial flora of the female genital tract causes bacterial vaginosis, which predisposes to different infections in which anaerobes are frequently encountered. These are usually mixed and include endometritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and tubo-ovarian abscesses, as well as obstetric infections such as amnionitis, septic abortions, septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, and postsurgical wound infections.

Pelvic inflammatory disease is associated in 30-40% of cases with anaerobes; these infections and their sequelae result in high rates of infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and premature delivery.

Anaerobic pathogens encountered are Peptostreptococcus spp., Prevotella spp., Porphyromonas spp., and members of the clostridia family. B fragilis is not usually involved in gyneco-obstetric infections but, when present, carries a poor prognosis. Actinomyces spp. and Eubacterium nodatum are associated with infections in women with intra-uterine contraceptive devices. In addition to targeting anaerobes, antimicrobial treatment should cover aerobic bacteria as well as atypical organisms such as chlamydia.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Clues to anaerobic pelvic infection are foul smelling discharge, presence of gas in tissues, and septic thrombophlebitis.

Laboratory Findings

The diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is suggested by secretions with a pH of > 4.5, a “fishy” odor when treated with 10% hydrogen peroxide, and visualization of “clue” cells.

SKIN, SOFT TISSUE, & BONE INFECTIONS

A wide variety of infections at these sites involve anaerobic bacteria. Specific pathogens depend on the mechanism of injury disrupting normal skin barrier defenses as well as on the state of the host’s immune system. Infections can be localized or widespread and life threatening and may invade deep structures such as bone.

Bite wounds and clenched fist injuries often involve anaerobes, but antibiotic coverage must also include oral aerobic organisms, in particular, Eikinella corrodens in human bites and Pasteurella multocida in animal bites. Infected decubitus ulcers, pilonidal and sebaceous cysts, diabetic foot and burn wound infections, breast abscesses, and paronychia (mainly in children who suck their thumbs) have a polymicrobial flora in which anaerobes are present.

Involvement of the fascia leads to serious infections including necrotizing fasciitis and soft tissue gas gangrene (associated with C perfringens). When the perineal and scrotal regions are affected, this syndrome is known as Fournier’s gangrene.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms in general range from pain, erythema, swelling, and suppuration at the site of infection to bacteremia, sepsis syndrome, and tissue crepitance in the most serious cases. The absence of fever may reflect overwhelming infection.

Laboratory Findings

Microbiologic diagnosis is difficult and superficial swabs are usually not helpful. Deep tissue specimens obtained surgically are preferred in severe cases or when prolonged therapy is anticipated. The organisms that are most frequently encountered in diabetic foot and decubitus ulcer infections include B fragilis, Fusobacterium spp., Prevotella melaninogenica, Porphyromonas, Peptostreptococcus, and members of the Clostridium genus. Gas gangrene is associated with C perfringens and C septicum. Necrotizing fasciitis involves Bacteroides spp. as well as clostridia.

BACTEREMIA

Anaerobes cause from 5 to 10% of all bacteremias. B fragilis and related species account for 60-80% of all cases, followed by clostridia and peptostreptococci. Organisms such as Propionibacterium usually represent contamination of blood cultures by skin organisms. For true bacteremias, the common portals of entry are the gastrointestinal tract, female genital tract, lower respiratory tract, head and neck, and skin. Fewer than 5% of neutropenic bacteremias are secondary to anaerobes.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Clinical presentation will depend on the site of primary infection and can include fever, chills, and malaise. As previously mentioned, clostridial bacteremias should prompt the search for colonic malignancies.

OSTEOMYELITIS

It is not uncommon to find anaerobes in cases in which the predisposing factor is vascular insufficiency as in diabetic foot ulcers. Other examples are skull or facial bone infections arising from chronic otitis media, sinusitis, or mastoiditis. Clinically, these infections tend to run indolent courses and may occasionally present with foul smelling drainage through sinus tracts. Gram-negative bacilli and peptostreptococci are frequently involved.