Essentials of Diagnosis

- Key signs and symptoms may include minimally productive cough, low-grade fever, headache, and altered mental status.

- Risk factors include smoking, advanced age, history of cardiac or pulmonary disease, male gender, and cell-mediated immune suppression.

- Common infections include pneumonia with multisystem involvement (Legionnaires’ disease) and nonspecific febrile illness without pulmonary involvement (Pontiac fever).

- Gram stain of respiratory secretions may reveal numerous neutrophils without evident organisms.

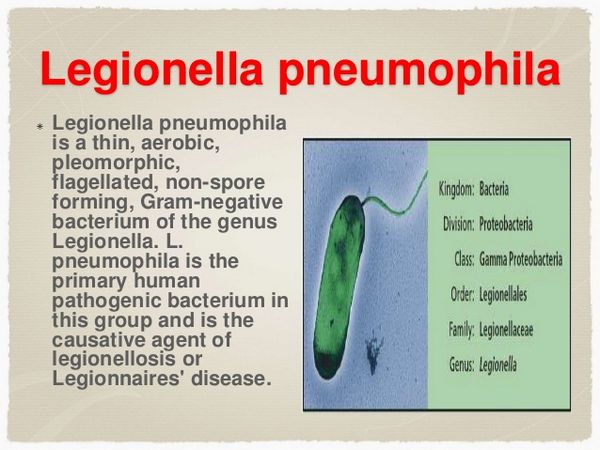

- Aerobic, pleomorphic, faintly staining gram-negative rods are non-spore forming and unencapsulated.

General Considerations

Epidemiology

More than 25 species and 48 serogroups of Legionella have been identified. Legionella pneumophila (especially serogroup 1) causes ~ 70-80% of cases of legionellosis, but L micdadei, L bozemanii, L dumoffi, L feelei, L longbeacheii, and other species are also pathogenic. The true incidence of legionellosis, which includes Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever, is difficult to establish. Although most developed countries conduct surveillance for infection, underdetection is common, in part because laboratory tests are often not performed or, when performed, lack sensitivity.

Between 500 and 1500 cases in the United States are reported annually to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), but the true incidence is believed to be between 13,000 and 20,000 cases a year. Few population-based incidence studies have been conducted. Among members of a prepaid health plan in Seattle, Washington, the annual incidence was 12 cases per 100,000 between 1963 and 1975. In Nottingham, England, 1.4 cases per 100,000 population occurred annually between 1977 and 1991.

Legionella species have been detected in virtually all sources of fresh water, including lakes, ponds, rivers, and soil runoff, especially in areas where there is thermal pollution. However these natural water supplies are rarely identified as sources of human infection. Aerosols from artificial reservoirs of water, including cooling towers, evaporative condensers, air conditioners, humidifiers, fountains, and whirlpool spas, are most often implicated in outbreaks. Cooling towers and evaporation condensers are especially prone to

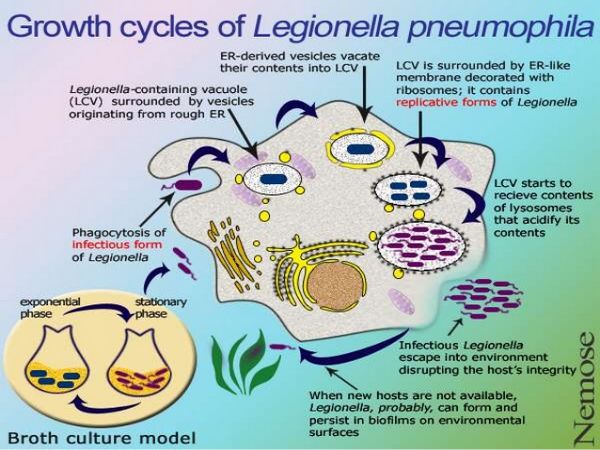

Legionella colonization because they recycle warm, unfiltered water and accumulate organic debris and biofilm over time. This milieu supports the growth of other microflora, including amoebae. Amoebae may be essential to the life cycle of Legionella species; the organism appears to multiply intracellularly in these protozoa in the same way it multiplies in human monocytes. Removal of amoebae by filtration will also eliminate viable Legionella species from water reservoirs.

Potable-water (especially hot-water) distribution systems are also important reservoirs supporting growth of Legionella species. Environmental sampling in hospitals, hotels, and homes has demonstrated colonization in 10-50% of hot-water faucets or water heaters, even at sites where no cases of legionellosis have occurred. Electric water heaters are especially prone to colonization because, unlike gas systems that apply heat to the bottom of the tank, electrical heating elements are in the sides of the tank. The temperature of the sediment deposited in the bottom of the tank is thus cool enough to support growth of the organism. Temperature appears to influence the risk of Legionella colonization in all water systems. Growth is promoted between 35 °C and 45 °C, and organisms may remain viable at temperatures = 66 °C.

Legionella species are transmitted to humans through aspiration, inhalation, or instillation of infected water. There is no evidence to support person-to-person transmission. Cooling-tower exhausts proximate to air conditioning intake vents are an important cause of large outbreaks among occupants of hospitals, hotels, and other buildings. Transmission to persons residing as far as 1-2 miles from the cooling towers has also been suggested.

Residential air conditioners that do not use water for cooling do not promote Legionella transmission, but home air humidifiers probably do. Showers, faucets, and respiratory therapy equipment have also been sources of outbreaks. One major outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease on a cruise ship, involving at least nine separate week-long cruises, was associated with contamination of a whirlpool spa. The water taken aboard the ship probably contained L pneumophila, but the potable water supply was properly disinfected (chlorinated) before consumption. However, the water reserved for the spa was not adequately decontaminated by the brominator. L pneumophila colonized the organic debris trapped in the sand filter of the spa, creating the potential for infectious aerosols that caused exposure and infection among passengers. In another important outbreak, the humidification mist used to preserve vegetables in a grocery store was linked to transmission of legionellosis to several shoppers.

The sources of sporadic cases of Legionella infection are not clear, although > 65% of known cases are not associated with outbreaks. Given the enormous number of potential water sources, it is not surprising that establishing a source of exposure is difficult in the absence of an obvious outbreak. As mentioned above, persons residing near cooling towers may be at increased risk. Tobacco use, alcohol abuse, and conditions that affect pulmonary defense mechanisms are risk factors for legionellosis. Some experts believe that aspiration of infected potable water may be an important source of sporadic and also epidemic legionellosis.

Nosocomially acquired Legionnaires’ disease accounts for ~ 23% of all cases reported to CDC. After one case of nosocomial infection is identified, subsequent cases are usually detected. Hence, the CDC recommends that identification of one definite or two possible cases of nosocomial Legionnaires’ disease within 6 months should prompt an epidemiologic investigation and intensified surveillance. The capacity of Legionella species to colonize hospital plumbing systems for prolonged periods provides an ongoing source for transmission to patients. In older facilities or in those in which renovation results in areas of water stagnation and build-up of organic and inorganic sediments, Legionella colonization is not uncommon. In one recent investigation, the hospital water distribution system was associated with cases of Legionnaires’ disease among immunosuppressed patients over a period of 17 years. Mortality from nosocomially acquired Legionnaires’ disease in the United States is ~ 40%, compared with 20% for community-acquired cases.

Microbiology

Legionella species are slender, aerobic gram-negative bacilli that may appear as coccobacilli measuring 1-2 um in clinical specimens. Legionella species are fastidious; visible colonies appear on agar only after 2-7 days of culturing at 35 °C. Buffered charcoal yeast extract agar is the preferred culture medium. Legionella species are not encapsulated and do not form spores. They are catalase positive and oxidase negative.

Pathogenesis

Legionella species reach the lower respiratory tract via aspiration, inhalation, or instillation of infected water. They are facultative intracellular bacteria that infect host alveolar macrophages and reside within ribosome-lined phagocytic vacuoles. Much as the organism evades the lysosomal defenses of host amoebae, it interferes with macrophage lysosomal fusion and multiplies within that cell’s phagosome. New bacilli are released when the infected macrophage ruptures. This process initiates the inflammatory response and pulmonary infiltrates that are the hallmark of Legionnaires’ disease. Humoral antibodies develop in infected persons as well as those with subclinical exposures, but they do not appear to be protective. However, cell-mediated responses may confer resistance to subsequent infections. Cytokine production, which activates macrophages and enhances intracellular killing of Legionella species, may also be an important host defense.

Legionella: Clinical Syndromes

BOX 1. Legionella Syndromes

Legionnaires’ Disease

Pontiac Fever

More Common

- Pneumonia

- Self limited, acute flulike illness characterized by malaise, myalgia, fever, chills, and headache

Less Common

- Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain

- Lethargy, encephalopathy

- Hypotension, adult respiratory distress syndrome

- Nonproductive cough, nausea

Among immunosuppressed patients, extrapulmonary disease has included sinusitis, cellulitis, pericarditis, endocarditis, pyelonephritis, pancreatitis, and perirectal abscess.

BOX 2. Treatment of Legionnaires’ Disease

Adults

Children

First Choice

- Erythromycin, 2 g orally daily in divided doses or 4 g IV daily in divided doses (latter dosage is associated with reversible ototoxicity)

OR

- Azithromycin, 500 mg IV daily

- Clarithromycin, 500 mg orally twice daily

- Levofloxacin, 250-500 mg orally or IV daily

- Ciprofloxacin, 500-700 mg orally twice daily; 200-400 mg IV every 12 h

- Ofloxacin, 200-400 mg orally or IV every 12 h

- Erythromycin, 30-60 mg/kg orally daily in divided doses

OR

- Azithromycin (age > 2 y), 12 mg/kg orally daily (not to exceed 500 mg/d)

- Clarithromycin (age > 6 mo), 7.5 mg/kg orally twice daily (not to exceed 500 mg/dose)

Second Choice

- Doxycycline, 100 mg orally or IV every 12 h

- Doxycycline, (age > 8 y), 2-4 mg/kg orally daily in two doses

Considerations for Immunosuppressed Patients

- Combination treatment with macrolide/azolide plus quinolone or macrolide/azolide plus rifampin

When treating transplant recipients, consider the influences of macrolides and rifampin on cyclosporine metabolism; a quinolone alone may be preferable.

BOX 3. Prevention and Control of Legionella Infection

Isolation Requirements

None indicated. No evidence of person-to-person transmission

Environmental Control

- In hospitals with a significant immunocompromised population, superheating and flushing of water supplies identified as reservoirs of L pneumophila has been attempted with variable success.

- Adjunctive use of copper-silver ionization and ultraviolet systems has been reported effective. Hyperchlorination is no longer recommended.

- Drain, scrub, and disinfect water reservoirs; periodic maintenance treatment required.