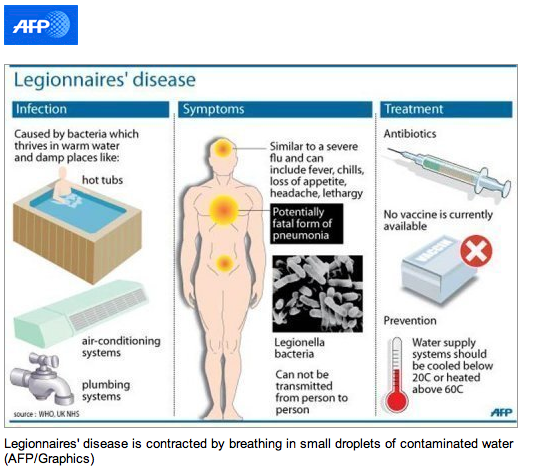

Legionella species are associated with outbreaks of either Pontiac fever, a self-limited influenzalike condition in otherwise healthy people, or Legionnaires’ disease, a severe pneumonic disease more common among elderly and immunocompromised individuals (Box 1). The spectrum of illness is much broader than these two clinical entities suggest, ranging from completely asymptomatic infection to fulminant respiratory failure and death.

PONTIAC FEVER

In 1968, the first documented outbreak of Pontiac fever syndrome affected people in a health department building in Pontiac, Michigan. Epidemiologic investigation demonstrated that the infection was airborne and implicated water aerosols that were produced by a faulty air conditioning system as the source of exposure. Sentinel guinea pigs exposed to air in the building developed bronchopneumonia, and lung tissue cultures grew L pneumophila (serogroup 1). Paired acute and convalescent serum specimens from 37 patients were tested by the indirect fluorescent antibody technique, using L pneumophila serogroup 1 antigen, and 31 (84%) had rises in titer from < 32 to = 64. Since that time, numerous outbreaks of Pontiac fever, almost always attributable to an obvious source of contaminated water, have been detected in communities across the country.

Pontiac fever is a self-limited infection characterized by fever, chills, headache, myalgia, fatigue, and upper respiratory tract symptoms. It is not associated with a pneumonia or pulmonary infiltrates, although some patients do have a mild nonproductive cough. The incubation period is short, usually 36 h, and the attack rate is high (= 95%), even among individuals with no underlying illness. Patients recover spontaneously, usually within 1 week of symptom onset.

LEGIONNAIRES’ DISEASE

Legionella species cause both community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonia among normal individuals, as well among those with depressed cell-mediated immunity (transplant recipients, patients treated with corticosteroids, and those with AIDS). Immunosuppressed patients, those who smoke tobacco, elderly persons, and patients with underlying cardiovascular and pulmonary illnesses are at increased risk. Men are two- to threefold more likely than women to acquire this infection.

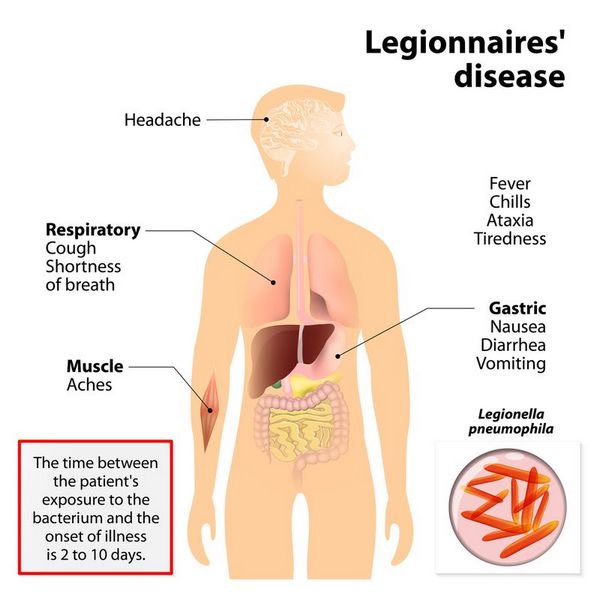

Unlike Pontiac fever, for which the incubation period is short (1-2 days), the onset of Legionnaires’ disease may occur = 14 days after exposure, although onset usually occurs within 2-10 days. The attack rate is also relatively low (< 8%), when compared with Pontiac fever.

Signs and Symptoms

The clinical severity of Legionnaires’ disease is highly variable. In mild cases, dry cough and low-grade fever are predominant symptoms. Severe cases, especially among immunosuppressed patients, are complicated by multisystem organ failure and adult respiratory distress syndrome.

Early symptoms are nonspecific and do not distinguish Legionnaires’ disease from other causes of pneumonia. Common symptoms include fever, headache, malaise, myalgia, nausea, anorexia, and a minimally productive cough. Neurologic symptoms in addition to headache include changes in mental status that range from lethargy to encephalopathy. Chest pain, which may be pleuritic, and modest hemoptysis are sometimes associated with this infection. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain occur in a minority of patients.

Laboratory Findings

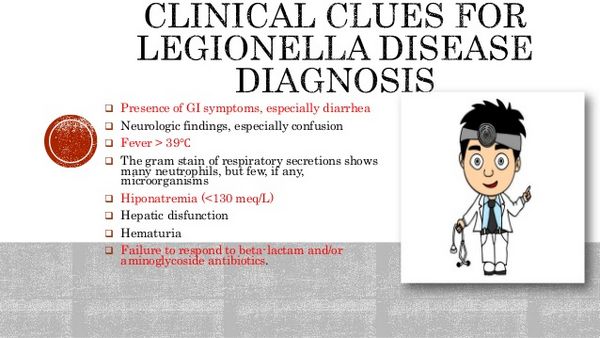

Laboratory abnormalities are nonspecific, although hyponatremia (Na < 130 mEq/L) is more likely in legionellosis than in other causes of pneumonia.

Imaging

Chest x-ray findings are almost always present by the third day of illness and tend to begin as a unilateral lower-lobe infiltrate. The infiltrate may progress despite antibiotic treatment, but the degree of radiographic abnormality does not correlate with severity of clinical illness. In one recent report, cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, creatinine (= 1.8 mg/dL), septic shock, progressive infiltrates, mechanical ventilation, hyponatremia, and blood urea levels (= 30 mg/dL) were factors related to poor outcome, but appropriate antibiotic treatment and improvement in chest radiographic appearance were favorable prognostic factors. Multivariate analysis showed that an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II [see Rutledge et al, 1991]) score of = 15 at admission and severe hyponatremia were independent predictors of mortality.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes pulmonary embolus as well as the usual bacterial and viral causes of pneumonia. A prospective study designed to identify factors that distinguished Legionnaires’ disease from other causes of community-acquired pneumonia in the emergency department of a university hospital was recently published. Epidemiologic and demographic data and clinical, laboratory, and radiologic features of patients with Legionnaires’ disease were compared with those of patients with community-acquired pneumonia caused by other bacterial pathogens. Legionnaires’ disease was more frequent in middle-aged, healthy alcohol-drinking male patients than other causes of pneumonia. Lack of response to initial treatment with ß-lactam antibiotic and headache, diarrhea, severe hyponatremia, and elevation in serum creatine kinase levels on presentation were also more common among patients with Legionnaires’ disease. In contrast, cough, sputum production, and thoracic pain were less common in Legionnaires’ patients than in other pneumonia patients. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that underlying disease, diarrhea, and elevation in the creatine kinase were independent predictors of Legionnaire’s disease.

Complications

In the increasingly large population of immunocompromised individuals, Legionella species have been documented to cause extrapulmonary disease that can include cellulitis, wound infection, perirectal abscess, pancreatitis, pyelonephritis, peritonitis, hemodialysis fistula infection, pericarditis, myocarditis, and prosthetic valve endocarditis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Legionella infection depends on a high index of suspicion and special laboratory tests. Definitive diagnosis of legionellosis is based on recovery of the organism from respiratory secretions or tissues. Cultures of sputum, transtracheal aspirates, and blood are each 100% specific, although the sensitivities are 80%, 90%, and 20%, respectively. Pretreating respiratory specimens with acid and use of selective media can improve culture sensitivity. In special cases, coculture with amoebae or intraperitoneal inoculation of guinea pigs will increase the diagnostic yield.

Serologic comparison of acute and convalescent serum specimens demonstrating a fourfold rise in titer (= 128) of immunoglobulin G antibody (indirect fluorescent antibody assay) is > 95% specific when the L pneumophila serogroup 1 antigen is used (but less specific with other Legionella antigens) and demonstrates a sensitivity of ~ 50%. Clinical utility of serologic diagnosis is limited, however, because 4-12 weeks are required for the human body to mount a full antibody response. This test is therefore mainly useful as an epidemiologic tool.

Direct fluorescent antibody tests can identify Legionella antigens in respiratory specimens and tissue with a high degree of specificity, but, as with other tests, the direct fluorescent antibody test is not sensitive (< 60%). Commercially available tests for excreted urinary antigen detect only infections caused by L pneumophila serogroup 1, but because this serogroup accounts for > 70% of Legionella infections, they are useful rapid tests in many clinical settings.

Finally, tests using polymerase chain reaction amplification of ribosomal RNA and DNA sequences specific to L pneumophila are now available and have been demonstrated to be sensitive and specific for confirming the presence of the organism in cultures. However, the sensitivity of these tests when performed on respiratory tract samples may not be better than that of direct fluorescent antibody tests, and their specificity is worse.

Treatment

Erythromycin is the recommended treatment for Legionnaires’ disease and other serious Legionella infections; however, failures have occurred, and adverse effects are common (Box 58-2). Erythromycins, intravenous azithromycin, and levofloxacin are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of Legionnaires’ disease. Although prospective controlled comparisons have not been performed, clarithromycin and quinolone antibiotics are also effective. Other agents with activity against Legionellaceae include doxycycline, minocycline, rifampin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. For severe illness and for treatment of immunosuppressed patients, combination treatment either with rifampin plus a macrolide or quinolone or with a quinolone plus a macrolide (eg, levofloxacin plus azithromycin) is recommended.

Prevention & Control

Isolation of patients with known or suspected Legionella infection is not required, because direct person-to-person transmission has not been observed (Box 3). Epidemiologic investigation of sporadic community-acquired cases of Legionella infection is not usually productive because of the large number of exposures to potential water sources. When a community outbreak is suspected, conventional epidemiologic methods (ie, case definition, hypothesis generation, and case control study) should be used to confirm the presence of an outbreak and identify the source of exposure. Samples from suspicious water reservoirs should be cultured, and in some cases the potential for these sources to produce aerosol particles in the respirable size range should be evaluated with an air particle-size sampler. Smoke or other tracer materials can be used to evaluate the movement of aerosols and routes of access to ventilation systems, air intake passages, or other modes of dispersion.

In cases of known or suspected nosocomial infection, a detailed environmental investigation of all sources of water exposure is often indicated, especially when two or more unexplained cases have occurred. In addition to evaluating water reservoirs in the facility (eg, cooling towers and evaporative condensers), respiratory-therapy equipment should be checked and procedures should be reviewed to identify occult sources of exposure to potable water. In addition, samples from the water distribution system (eg, showers, faucets, and taps) should be cultured for Legionella species.

It is very difficult if not impossible to decontaminate water supplies. Cooling towers and evaporative condensers must be drained, scoured to remove organic debris and sediment, and then disinfected with chlorine. Follow-up maintenance must include periodic chlorination or treatment with alternate disinfectants. Similarly, contaminated water heaters should be drained, cleaned, and then disinfected. Superheating (> 60 °C) is also recommended for water heaters and distal water distribution systems. However, this procedure can result in severe scalding and must be used with caution. Hyperchlorination has also been used, but can result in high levels of trihalomethanes, which are putative carcinogens. Over time, hyperchlorination corrodes the plumbing system, leading to enhanced opportunities for sediments that promote the growth of Legionella species.

Metal ionization procedures are advocated by some, but are not known to work better than conventional methods. One copper-silver ionization system was sequentially installed onto the hot-water recirculation lines of two hospital buildings colonized with L pneumophila serogroup 1. A third building with the same water supply, also colonized with L pneumophila, served as a control. Within 4-12 weeks of application, the levels of detectable L pneumophila in the two treated systems dropped to zero, but remained positive in the untreated system. However, concentrations of copper and silver in excess of Environmental Protection Agency standards can accumulate at the bottoms of hot-water tanks subjected to this type of treatment. Its long-term effectiveness has not been determined.

In cases in which water treatments fail, the entire current and past water distribution system engineering and structural design should be reviewed to identify old pipes that may bypass the part of the system undergoing disinfection. These pipes may introduce contaminated water downstream if they are not disinfected.

Detailed guidelines for preventing nosocomial legionellosis and for decontaminating water reservoirs and distribution systems are available from CDC at http://www.cdc.gov.ncidod/diseases/hip/pneumonia/pneu_mmw.htm.