Essentials of Diagnosis

- Most common in the northeastern, upper midwestern, and western parts of the United States.

- Borrelia burgdorferi is the longest (20-30 um) and narrowest (0.2-0.3 um) spirochete member of the Borrelia genus and has the fewest flagella (7-11).

- Erythema migrans (EM) is a red expanding lesion with central clearing that is commonly seen during the early stage of Lyme disease.

- The most common systems affected are the skin (EM), the joints (arthritis), the CNS (facial palsy), and the heart (conduction defects).

- Serology is not standardized; it is insensitive in early infection and does not distinguish active from inactive infection.

- Grows in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly medium from skin biopsy and other specimens.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be useful in synovial-fluid analysis. It has limited value with blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and urine.

General Considerations

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by the spirochete B burgdorferi. Lyme disease can be divided into early disease (stage 1, EM), disseminated infection (stage 2), and late disease (stage 3, persistent infection). The first stage involves the skin, followed by stages 2 and 3, which often affect the skin, joints, CNS, and heart. However, any of the stages may fail to appear or may overlap with one another (Table 65-2).

Epidemiology

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne infection in the United States. In 1997, there were 12,801 cases reported in the United States. It is transmitted by ticks from the genus Ixodes. The Ixodes tick goes through a 2-year life cycle that is composed of three stages: larva, nymph, and adult. Tick larvae acquire the spirochete via a blood meal from an infected host. Both the nymph and female adult infect humans.

A tick must be attached for at least 24 h to transmit the spirochete. Tick engorgement and attachment for = 72 h are predictors of subsequent human infection. Ixodes ticks in the northeastern and midwestern United States belong to the Ixodes dammini (scapularis) species, in the western United States to Ixodes pacificus, in Europe to Ixodes ricinus, and in Asia to Ixodes persulcatus. Rodents and small mammals are the natural hosts of the larval and nymphal stages.

The incidence of Lyme disease reflects a changing dynamic between the principal reservoir, the white-footed mouse, its food supply, and the suitability of its local habitat. Deer, horses, dogs, and other larger mammals and birds may be occasional hosts to the adult ticks. Most cases have their onset during summer and occur in association with hiking, camping, and residence in wooded, rural, or coastal areas.

Microbiology

Of spirochetes in the Borrelia genus, B burgdorferi is the longest (20-30 um) and narrowest (0.2-0.3 um), and has the fewest flagella (7-11). This organism can be grown from skin biopsy and other specimens on an artificial medium called Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly at 33oC. The B burgdorferi surface membrane is studded with lipoproteins called outer-surface proteins (OSPs) A, B, C, D, E, and F; other prominent flagellar antigens include flagellar protein, heat shock protein, and protoplasmic cylinder antigen.

B burgdorferi is capable of altering its surface lipoproteins by recombining gene cassettes in a manner that resembles the mechanism of antigenic variation among the relapsing fever borreliae. The antigenic variability seen among different isolates has important implications for serologic tests and vaccine development. In the United States, most strains belong to the genomic group B burgdorferi sensu stricto, and in Europe most strains belong to the groups known as B garinii and B afzelii.

Pathogenesis

After inoculation in the skin, B burgdorferi replicates within the dermis producing EM and spreads hematogenously to other organs. The organism has tropism for the skin, joints, heart and CNS. A rise in immunoglobulin M (IgM) is detected within 2-3 weeks after the onset of infection; an increase in IgG and IgA is established after 2-3 months of infection. Host genetic factors may determine the likelihood of tissue damage; for example, patients with human leukocyte antigens DR4 and DR2 may be more susceptible to chronic arthritis.

Clinical Findings

Signs and symptoms

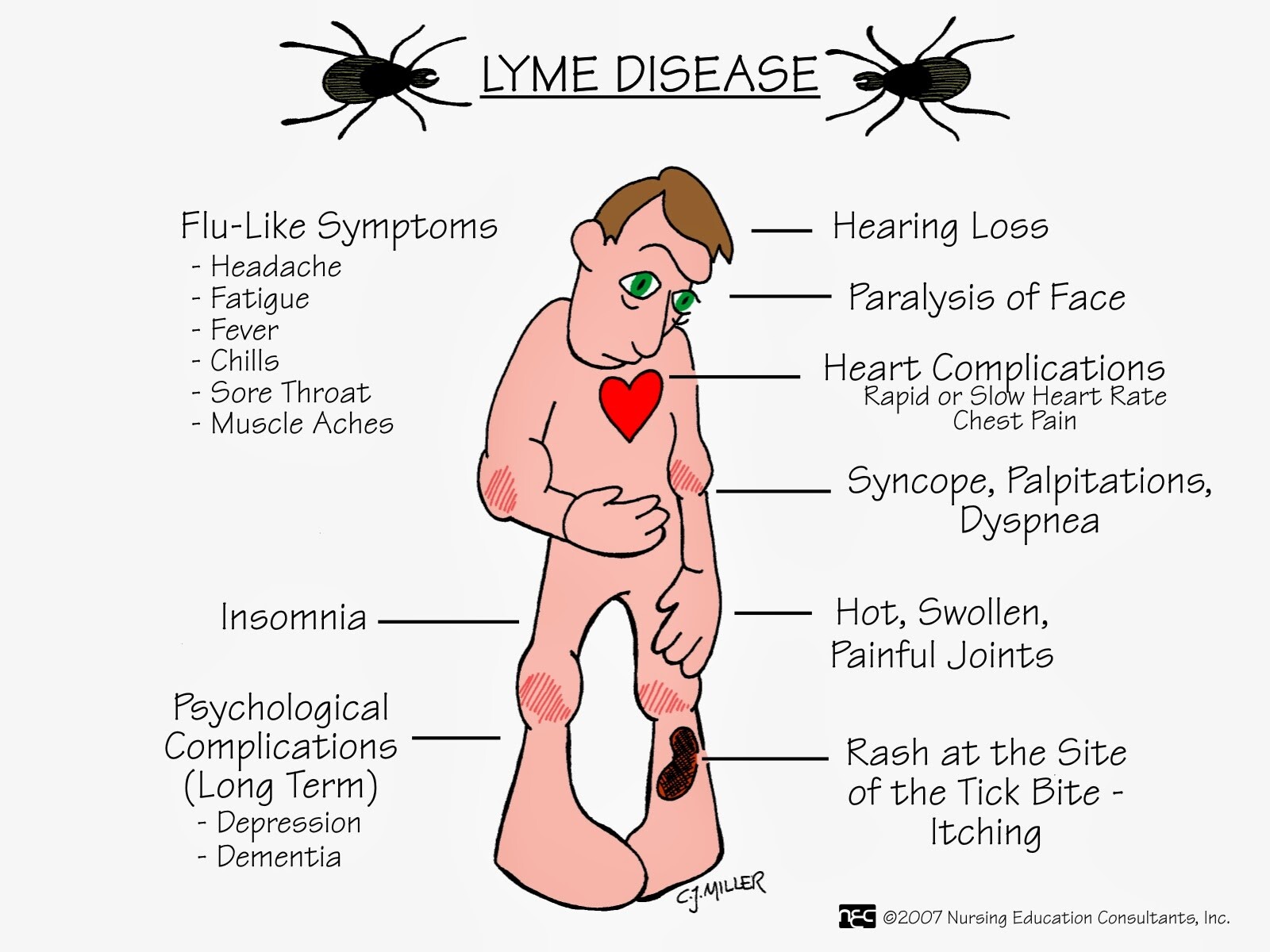

B burgdorferi infection can involve the skin, musculoskeletal system, CNS, and cardiac tissues (Box 4).

Skin

EM appears at the site of the tick bite 3-30 days after the bite and begins as a red macule or papule with areas of redness that expand with partial central clearing. The lesion often feels warm to hot; it may burn, prickle, or itch, and it is more common in the thigh, groin, and axilla. The lesion usually fades within 3-4 weeks (range, 1 day-14 months). The migratory nature of skin lesions most likely represents spirochetemia with secondary seeding of the skin rather than multiple tick bites.

EM may be accompanied by fatigue, fever, chills, achiness, headache, and lymphadenopathy. It can also present with CNS and liver involvement. Multiple annular secondary lesions tend to be smaller and less migratory and to lack indurated centers. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans lesions follow years after EM. There is usually bluish-red discoloration, and then the lesion becomes sclerotic or atrophic. This condition has been associated with elevated antibodies to B burgdorferi and usually responds to antibiotic therapy; it is seen primarily in elderly women in Europe.

Musculoskeletal system

Joint symptoms are the second most common clinical manifestation after EM. These symptoms may begin 5-6 weeks (range, 1 week to 2 years) after the bite, and they include, at one end of the spectrum, subjective joint pain, and at the other, arthritis or chronic erosive synovitis. The arthritis is usually of sudden onset, monoarticular or oligoarticular, and migratory. The knee is the most frequently involved joint, followed by the shoulder, elbow, temporomandibular joint, ankle, wrist, and hip. Initially, recurrent attacks of arthritis are common, but their frequency decreases by 10-20% each year.

During recurrences, usually more joints are involved than in the initial episode. These attacks last ~ 1 week, with intervals of 1 week to 2 years between attacks. Joint fluid leukocyte counts range from 500 to 110,000 cells/mm3. Of all patients with Lyme disease, ~ 10% develop a severe chronic erosive arthritis often associated with IgG antibody response to OSPs A and B of the organism and with human leukocyte antigen DR4.

CNS

Neurologic abnormalities begin within 4 weeks (range, 2-11 weeks) after the tick bite. The most common symptoms are headache, stiff neck, photophobia, facial palsy, and peripheral nerve paresthesias. CSF findings are similar to those seen in viral meningitis with lymphocytic pleocytosis of ~ 100 cells/mm3 and elevated protein levels. Cranial nerve VII is the most frequently involved; unilateral or bilateral facial palsies occur in 11% of patients, and these findings can be seen in 50% of patients with meningitis.

Other cranial nerves, particularly III, IV, V, and VIII, are less often involved. Months to years after the initial infection, patients may have chronic encephalopathy (manifested by memory impairment, mood changes, sleep disturbances, and difficulty with concentration), polyneuropathy, or, less commonly, leukoencephalitis. These patients may present with neuropsychiatric symptoms, focal CNS disease, or severe fatigue. However, it is often difficult to establish B burgdorferi as the etiologic agent in patients who present with fatigue or psychiatric manifestations.

Cardiac tissue

Cardiac involvement begins within 5 weeks (range, 3-21 weeks) after the bite, in ~ 5-10% of patients. Such abnormalities usually consist of atrioventricular block (first degree, Wenckebach, or complete heart block) and can last for 3 days-6 weeks. Some patients can present with myopericarditis, pericardial effusion, and chronic cardiomyopathy.

Other clinical findings

Other unusual manifestations include ophthalmologic involvement (conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis, choroiditis, retinal detachments, and optic neuritis), hepatitis, myositis, dermatomyositis, eosinophilic lymphadenitis, and adult respiratory distress syndrome.

Congenital infection

Maternal-fetal transmission of B burgdorferi has been reported with adverse fetal and neonatal outcome in a few cases (congenital heart disease, encephalitis, cortical blindness, intrauterine fetal death, and premature birth). Of note, a prospective study found no association between congenital malformation and infection by B burgdorferi. Despite the fact that there is no definitive proof that B burgdorferi causes fetal damage or an adverse outcome in the offspring, prompt diagnosis in the mother and treatment should be emphasized.

Laboratory findings

The diagnosis of Lyme disease is made on clinical findings, epidemiologic features, and an elevated antibody response to B burgdorferi. The available laboratory tests (with the exception of a positive culture from an EM lesion) can be unreliable. Serologic testing only should be undertaken when clinical and epidemiologic features suggest Lyme disease as the diagnosis. Most patients with B burgdorferi are found to have detectable antibodies when tested with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (60-70% within 2-4 weeks of infection and 90% by the disseminated and persistent stages).

However, serologic tests lack standardization, their accuracy is often unsubstantiated, and false-positive results are common. IgM antibody appears 2-4 weeks after the EM lesion, peaks at 6-8 weeks, and declines after 4-6 months. IgG antibody appears 6-8 weeks after the EM lesion, peaks at 4-6 months, and remains at low levels despite antibiotic therapy. A fourfold rise in antibody titer would be suggestive of recent infection. Western blot analysis is used to confirm results obtained by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The finding that a patient has significant amounts of anti-B burgdorferi-specific antibodies can be interpreted only in the context of the clinical setting.

Demonstrating that a patient has an immune response against this organism does not mean that the patient is actively infected or that any symptoms are necessarily related to B burgdorferi infection. Detection of spirochetal DNA by PCR is useful in synovial fluid (75-85% of sensitivity). However, the sensitivity of PCR in CSF, blood, or urine samples has not been well established.

Differential Diagnosis

Lyme disease mimics many different diseases (Table 3). The EM lesion may be confused with streptococcal cellulitis, erythema multiforme (the latter lesions tend to be smaller, urticarial, or vesicular and may occur on mucosal surfaces), and erythema marginatum (these lesions are smaller and migrate rapidly in minutes to hours). Lyme arthritis can be distinguished from other rheumatoid diseases, such as acute rheumatic fever, based on the EM lesion and the brief episode of synovitis.

The chronic form of Lyme arthritis may resemble pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s syndrome, and reactive arthritis caused by members of the Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, and Yersinia genera. This form of arthritis may also be associated with rubella, hepatitis B, or echoviruses. The aseptic meningitis in Lyme disease may resemble enteroviral, leptospiral, or early tuberculous meningitis. It is important to consider sarcoidosis, Behcet’s disease, and multiple sclerosis when the disease becomes chronic.

Treatment

Early disease responds readily to several oral agents (such as doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime), which are usually prescribed for 2-3 weeks (Box 5). There are few published, controlled trials that compare different regimens for late Lyme disease. Intravenous therapy, usually ceftriaxone or penicillin, is used for 2-3 weeks for late Lyme disease.

Erythema migrans

In EM, oral antibiotic therapy with doxycycline shortens the duration of the rash and prevents the development of late sequelae. Amoxicillin is also effective and preferred for children under 9 years of age and in pregnant or lactating women.

Musculoskeletal disease

Treatment for one month with oral doxycycline or amoxicillin is usually effective. For refractory cases, intravenous therapy with ceftriaxone or penicillin G, and arthroscopic synovectomy may lead to clinical improvement. Analgesics such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents should be used in patients with symptomatic arthritis.

Neurologic disease

Patients with facial nerve palsy alone can be treated with oral doxycycline or amoxicillin. Intravenous penicillin G, ceftriaxone, or cefotaxime is effective for meningitis, cranial or peripheral neuropathies, encephalitis, or other late neurologic complications.

Cardiac disease

Patients with cardiac atrioventricular block can be treated with doxycycline or amoxicillin if the PR interval is < 0.3 s. For those patients with more severe cardiac involvement, intravenous ceftriaxone or penicillin should be considered. High-degree atrioventricular block may require temporary pacing.

Prognosis

Most patients treated promptly with an appropriate antibiotic have an uncomplicated course. True failures are rare, and in most cases re-treatment or prolonged treatment is the result of misdiagnosis and misinterpretation of serologic results rather than inadequate therapy.

Prophylaxis

Routine use of antimicrobial prophylaxis after a tick bite is not recommended. However, some experts recommend amoxicillin for pregnant women who remove an engorged deer tick after exposure in an endemic area. Persons who develop a rash or illness within a month after a tick bite should seek prompt medical attention. Strategies to prevent Lyme disease include avoiding tick habitats, wearing protective clothing, using repellents to avoid tick attachment, promptly removing attached ticks, and using community measures to reduce tick abundance (Box 6).

The Lyme vaccine is made from recombinant OSP-A of B burgdorferi. Antibodies produced in response to the vaccine destroy spirochetes in the gut of the engorged tick before they can be transmitted. It is indicated for use in adults, in three doses intramuscularly at 0, 1, and 12 months. Ideally the third dose should be given in March because the tick season in the Northeast and upper Midwest usually begins in April.

The efficacy of the vaccine has been reported to be 76% after the third dose; however, the long-term safety, timing of booster doses, and cost effectiveness are unknown. Use of this vaccine should be limited to persons with frequent or prolonged exposure to tick habitats in endemic areas.