Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) are primarily childhood diseases. More than 70% of cases of impetigo are caused by S aureus, with the remainder attributed to pyogenic streptococci or mixed infection. Impetigo begins as a scarlatiniform eruption in a previously traumatized area that blisters then ruptures to form a wet, honey-colored crust. Common sites for infection are the face and trunk. The primary symptom in impetigo is localized pain; fever and constitutional symptoms are rarely seen (Box 1). Physical exam often reveals regional lymphadenopathy.

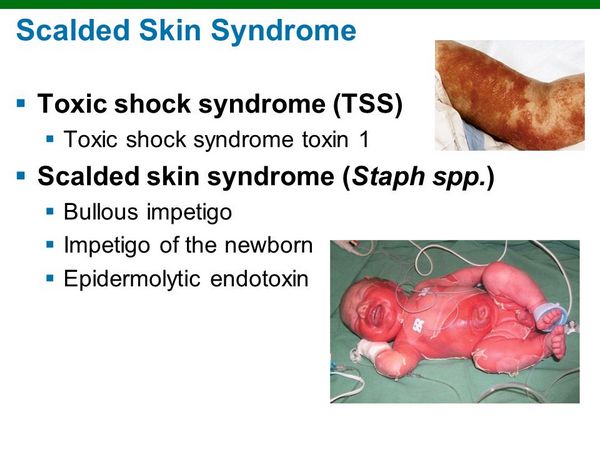

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome encompasses three distinct clinical scenarios: bullous impetigo, staphylococcal scarlet fever, and generalized scalded skin syndrome. The histologic finding common to all these conditions is cleavage of the epidermis at the level of the stratum granulosum caused by an exfoliative toxin. Bullous impetigo, the most common of the three types of SSSS, is almost exclusively seen in children < 5 years old. The disease begins as localized erythroderma progressing rapidly to form multiple vesicles, which coalesce into flaccid bullae.

Constitutional symptoms are minimal during the early phases, and the bullae spontaneously rupture after 1-2 days to form nontender, brown, varnishlike crusts. Commonly involved areas include the face, trunk, and perineum. A variant of this condition, staphylococcal scarlet fever, causes a scarlatiniform rash with late, limited desquamation, without an intermediate bullae stage.

Generalized scalded skin syndrome (known as Ritter’s syndrome in neonates) differs from the more benign bullous impetigo in that there is diffuse dermal involvement, causing extensive desquamation. Nikolsky’s sign, the sloughing of intact skin on light touch, is frequently seen. Following spontaneous bullae rupture, the skin is denuded and painful, and fever is common.

Laboratory Findings

Patients with generalized SSSS may have leukocytosis with a predominance of immature white cells. Blood cultures, particularly in adults, may be positive.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of impetigo includes herpes simplex and varicella zoster infections, contact dermatitis, scabies, and tinea corporis. SSSS may be confused with other bullous skin diseases (pemphigus vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid), Stevens-Johnson syndrome, thermal burn, and dermatitis herpetiformis.

Complications

Suppurative lymphadenitis, cellulitis, and staphylococcal sepsis are uncommon complications of impetigo. Complications of generalized SSSS include dehydration, bacteremia, and secondary infections. Mortality in children with generalized SSSS is 1-10%, whereas the mortality rate among adults is > 50%.

Diagnosis

Impetigo is diagnosed by the presence of the classic golden crusts on physical examination; a microbiologic diagnosis is rarely necessary. SSSS can be diagnosed by rupturing an intact bulla and culturing the extravasated fluid for S aureus. Latex agglutination or ELISA confirms the presence of the staphylococcal exfoliative toxin.

Treatment

Mild cases of (nonbullous) impetigo may be treated with topical mupiricin; however, more serious infections need oral antibiotics (Box 2). Bullous impetigo requires treatment with an oral antistaphylococcal agent. The high rates of morbidity and mortality in generalized SSSS mandate hospitalization for aggressive hydration and parenteral antibiotics. Extensive desquamation predisposes patients to secondary infections, and they should receive aggressive topical care such as that given to burn victims.