The following organisms are too rare to merit extensive discussion of clinical syndromes, diagnosis, and treatment.

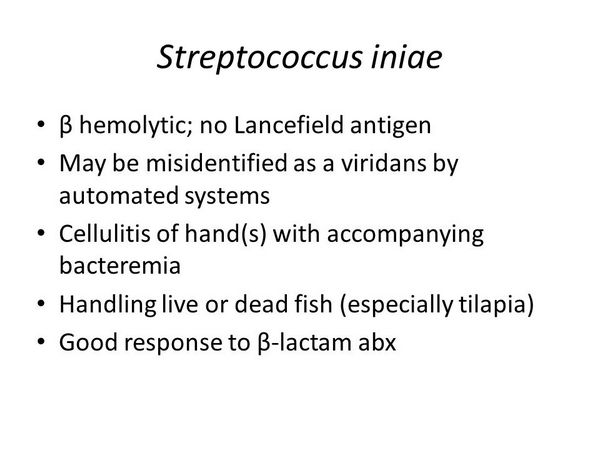

STREPTOCOCCUS INIAE

S iniae has recently been described as a cause of cellulitis, bacteremia, endocarditis, meningitis, and septic arthritis associated with the preparation of the aquacultured fresh fish tilapia.

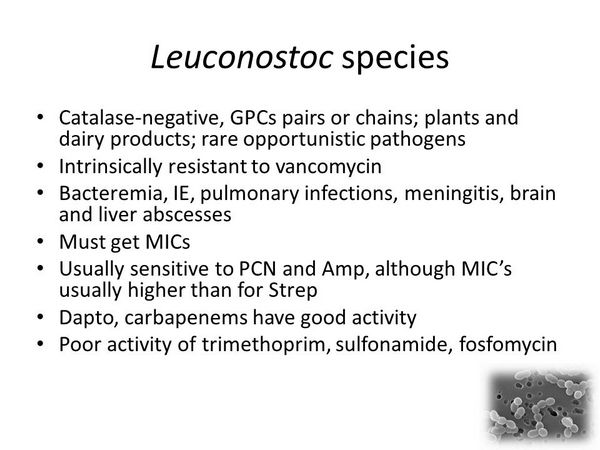

LEUCONOSTOC SPECIES

Leuconostoc spp. are gram-positive cocci or coccobacilli that grow in pairs and chains; Leuconostoc spp. may be morphologically mistaken for streptococci. They are vancomycin-resistant facultative anaerobes that are commonly found on plants and vegetables and less commonly in dairy products and wine. Leuconostoc spp. have been documented to cause bacteremias, intravenous line sepsis with localized exit site infection and/or bacteremia, meningitis, and dental abscess. Many patients with Leuconostoc spp. infection are severely ill, immunocompromised, or both.

Despite exhibiting resistance to vancomycin, Leuconostoc spp. are susceptible to most other agents with activity against streptococci, including penicillin, ampicillin, clindamycin, minocycline, erythromycin, tobramycin, and gentamicin. Some clinical data suggest that penicillin or ampicillin are the agents of choice for treating infections due to Leuconostoc spp.

PEDIOCOCCUS SPECIES

Pediococcus spp. are also vancomycin-resistant gram-positive cocci. They may be isolated from blood cultures, typically in immunocompromised patients.

STOMATOCOCCUS MUCILAGINOSUS

Stomatococcus mucilaginosus is a gram-positive coccus that may cause endocarditis, bacteremia, intravascular catheter infection, meningitis, and peritonitis. Many patients infected with S mucilaginosus have underlying serious diseases, neutropenia, the presence of foreign bodies, cardiac valvular disease, and/or a history of intravenous drug use.

Destruction of the oral mucous membranes because of chemotherapy or radiotherapy has been hypothesized to play a role in the dissemination of stomatococci from their normal habitat in the oral cavity. Resistance to penicillin has been documented among some S mucilaginosus strains, and susceptibility to other commonly used antimicrobials varies with the isolate. Stomatococci are uniformly susceptible to vancomycin.

AEROCOCCUS SPECIES

Although aerococci may appear as contaminants in clinical cultures, occasional reports of a clinically significant role of these organisms in cases of endocarditis, bacteremia, and urinary tract infection have been noted. Aerococci are susceptible to penicillin and vancomycin.

GEMELLA SPECIES

Gemella haemolysans has been isolated (as a pathogen) in cases of endocarditis, meningitis, and prosthetic joint infections.

G morbillorum has been isolated from blood, respiratory, genitourinary, wound, and abscess cultures and from an infection of an arterial-venous shunt. Gemella spp. appear to be susceptible to penicillin and vancomycin.

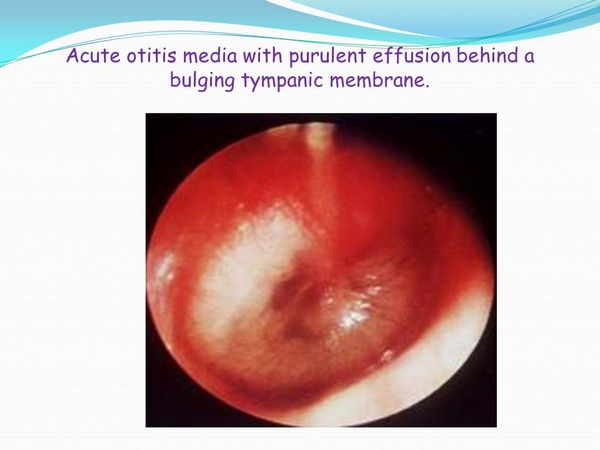

ALLOIOCOCCUS OTITIS

Alloiococci have been isolated from the middle ear fluid of children with chronic otitis media and a role for these organisms in the pathogenesis of persistent otitis media has been suggested.

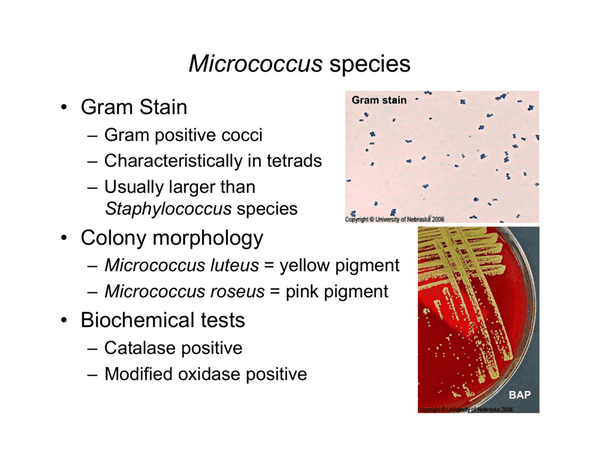

MICROCOCCUS SPECIES

Micrococci are frequently contaminants in clinical cultures but may occasionally cause infections such as infective endocarditis. A review of micrococcal endocarditis in cardiac surgery patients noted that MICs of penicillin ranged from 3.12 to 40.0 ug/mL and those of vancomycin spanned from 1.56 to 10.0 ug/mL. All of the isolates tested were susceptible to cephalothin.

LACTOCOCCUS SPECIES

Lactococcus spp. may be associated with bacterial endocarditis. Lactococci are susceptible to vancomycin and moderately susceptible to penicillin.

GLOBICATELLA SPECIES

Globicatella sanguis, the sole species in this genus, has been isolated from patients with bacteremia, urinary tract infection, and meningitis.

HELCOCOCCUS KUNZII

Helcococcus kunzii, the only member of this newly described genus, has been isolated from wound cultures, notably those from foot ulcers, characteristically as part of a mixture of bacteria. The clinical significance of this organism is not yet defined.

VIRIDANS GROUP STREPTOCOCCI, INCLUDING ABIOTROPHIA DEFECTIVA & ABIOTROPHIA ADJACENS

Essentials of Diagnosis

- Facultatively anaerobic gram-positive cocci, catalase negative, coagulase negative.

- a or ß hemolytic on blood agar.

- Abiotrophia defectiva and Abiotrophia adjacens require pyridoxal or thiol group supplementation.

- Streptococcus milleri group organisms often exhibit Lancefield antigens A, C, F, or G and often have a butterscotch odor.

General Considerations

Epidemiology

Viridans streptococci are part of the normal microbial flora of humans and animals and are indigenous to the upper respiratory tract, the female genital tract, all regions of the gastrointestinal tract, and, most significantly, the oral cavity. Clinically significant species that are currently recognized as belonging to the viridans group of streptococci include Streptococcus anginosus S constellatus, S cristatus, S gordonii, S intermedius, S oralis, S mitis, S mutans, S cricettus, S rattis, S parasanguis, S salivarius, S thermophilus, S sanguinis, S sobrinus, and S vestibularis.

Detailed studies of the ecology of strains in the oral cavity and oropharynx have been performed. The buccal mucosa and initial dental plaque are associated with S sanguis and S mitis, the dorsum of the tongue with S mitis and S salivarius, mature supragingival plaque with S gordonii, and subgingival plaque with S anginosus. In healthy individuals, adherence of viridans streptococci may provide “colonization resistance” within the oral cavity preventing the establishment of more pathogenic bacteria. Fibronectin, a complex glycoprotein found on the surface of oral epithelial cells, selectively promotes attachment of S salivarius, S mutans, and other gram-positive cocci to oral epithelial cells. If fibronectin is lost, as occurs in chronically ill or hospitalized patients, adherence of gram-negative bacilli to oral epithelial cells is increased, predisposing to the development of invasive gram-negative bacillary infections.

Viridans streptococci are strongly associated with bacterial endocarditis (see site). Notably, endocarditis caused by A defectiva and A adjacens carries a higher mortality rate than that reported for viridans streptococci overall. Relapse is reported more frequently in endocarditis cases caused by A defectiva and A adjacens. In endocarditis cases caused by other viridans streptococci, members of the S milleri group are associated with deep-seated abscesses in visceral organs.

Microbiology

Viridans group streptococci are facultatively anaerobic gram-positive cocci that do not produce catalase or coagulase and, on blood agar, are typically a or ? hemolytic. Although some isolates react with Lancefield grouping antisera, the species do not conform to the specific serogroups, and many isolates are entirely nongroupable. Resistance to optochin and lack of bile solubility can distinguish viridans streptococci from Streptococcus pneumoniae (which also produces a hemolysis on blood agar) . Most viridans streptococci grow well on conventional blood culture media. On solid agar, viridans streptococci are usually facultatively anaerobic, but some strains may be capnophilic or microaerophilic. The colonies vary in size and appearance depending on the composition of the medium and the atmosphere of incubation. In broth cultures, viridans streptococci appear as spherical or ovoid cells that form chains or pairs. The organisms are nonmotile and non-spore forming, and they ferment carbohydrates with acid but not gas production.

Viridans streptococci can be distinguished by their biochemical characteristics. S milleri, S constellatus, and S anginosus constitute the S milleri group of viridans streptococci. Members of the S milleri group of viridans streptococci often require CO2 for growth and typically grow as tiny colonies that may be a, ß, or ? hemolytic on sheep blood agar. Members of the S intermedius group often exhibit Lancefield antigens A, C, F, or G and often have a butterscotchlike odor.

A defectiva and A adjacens are defined by their requirement for pyridoxal or thiol group supplementation for growth. These organisms form satellite colonies around Staphylococcus aureus and other microbes, and their colonies are typically small.

Pathogenesis

Viridans streptococci have been considered to be bacteria of low virulence. An exception is those members of the S milleri group that have a propensity for producing localized purulent collections. The reasons for this pathogenic characteristic are unknown. Infections with viridans streptococci usually result from spread of organisms outside of their normal habitat, especially in patients at risk for endocarditis or immunocompromised patients. Their most important virulence trait consists of an ability to adhere to and propagate on cardiac valves, leading to endocarditis; the presence of extracellular dextran likely plays a role in this regard. In addition to causing infective endocarditis, certain species of viridans streptococci, notably S mutans, have a strong association with the development of dental caries. The high cariogenic potential of S mutans is thought to be related to its ability to adhere in large masses to teeth and to produce high concentrations of acid from the fermentation of dietary sugars.

Viridans Group Streptococci: Clinical Syndromes

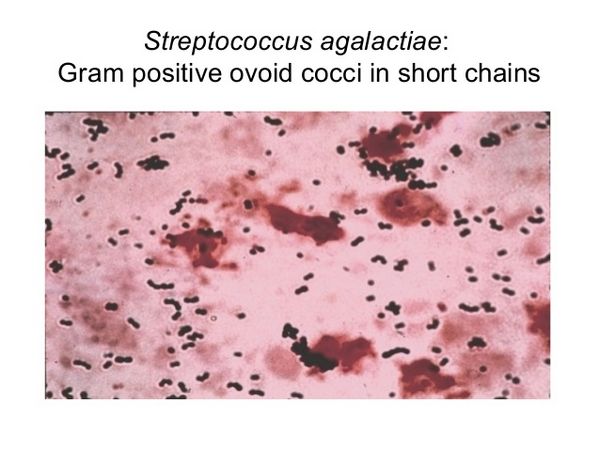

GROUP B STREPTOCOCCUS (S AGALACTIAE)

Essentials of Diagnosis

- Group B streptococcus (S agalactiae).

- Facultative gram-positive diplococci.

- Grayish white in color on sheep blood agar with a narrow zone of ß hemolysis.

- Group B cell wall antigen positive.

- Resistant to bacitracin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

- Hydrolyzes sodium hippurate.

General Considerations

Epidemiology

Group B streptococci are especially associated with neonatal and puerperal infections but cause infections in nonobstetric, nonneonatal populations as well. The incidence of early onset neonatal group B streptococcal infection (defined as the onset of symptoms during the first 5 days of life) is 1.3/1000 live births and appears to be declining. The attack rate for late onset neonatal infection (defined as onset of symptoms from 6 days to 3 months of age) is 0.5/1000 live births.

Group B streptococci colonize the mucous membrane of newborns via vertical transmission of the organism from the mother. This takes place either in utero via the ascending route or at the time of delivery. The rate of vertical transmission to neonates born to women colonized with group B streptococci at the time of delivery ranges from 20% to 72%. A high genital inoculum at the time of delivery is associated with a higher rate of vertical transmission. In addition, infants born to heavily colonized women are more likely to develop invasive early onset group B streptococcal disease. Heavily colonized infants have significantly increased rates of early and late onset group B streptococcal disease. Nosocomial transmission of group B streptococci may occur and may be influenced by poor hand washing by health care providers and by crowding.

Several factors have been identified that increase the incidence of invasive early onset infection among neonates born to colonized mothers. They include rupture of the membranes > 18 h before delivery; multiple births; premature rupture of the membranes (< 37-week gestation); maternal fever or amnionitis, or both; black race; age < 20 years; history of previous miscarriage; and preterm delivery.

Group B streptococci may be isolated from genital or lower gastrointestinal tract specimens or both of 5-40% of pregnant women. Lower socioeconomic status, having < three pregnancies, the presence of an intrauterine device, sexual activity, age of < 20 years, and the first half of the menstrual cycle are associated with an increased rate of detection of group B streptococcal colonization in the female genital tract, whereas being of Mexican-American heritage is associated with a decreased rate. Group B streptococci may be harbored in the urinary tract during pregnancy in association with asymptomatic bacteriuria; bacteriuria is a marker for high inoculum in the genital tract.

Group B streptococci are associated with postpartum febrile morbidity with or without bacteremia. In addition, adults with diabetes mellitus, chronic hepatic dysfunction, HIV infection, or malignancies requiring immunosuppressive therapy are also susceptible to group B streptococcal infections.

Microbiology

Group B streptococci are facultative gram-positive diplococci that are easily grown on a variety of bacteriologic media. On sheep blood agar, isolated colonies are 3-4 mm in diameter and grayish white in color. A narrow zone of ß hemolysis surrounds the flat, somewhat mucoid colonies, although a small number of strains may be ? hemolytic. Group B-specific cell wall antigen may be detected by countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, indirect immunofluorescence, staphylococcal coagglutination, or latex agglutination. Group B streptococci are resistant to bacitracin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, hydrolyze sodium hippurate, and produce an orange pigment during anaerobic growth on certain media. Group B streptococci produce CAMP (named for Christie, Atkins, and Munch-Petersen) factor, which is a thermostable extracellular protein that results in synergistic hemolysis on sheep blood agar in conjunction with the ß hemolysin of S aureus.

Pathogenesis

Preterm labor may be associated with an increased rate of symptomatic group B streptococcal infection in the neonate because ascending infection caused by group B streptococci may be a primary pathogenic event initiating preterm rupture of the membranes. Low levels of antibody to the capsular antigen of group B streptococci may predispose to neonatal infection. In addition, complement and heat-stable opsonins may play a role in the pathogenesis of group B streptococcal infections.

In addition to host factors, bacterial virulence factors contribute to the host-parasite interaction that determines the outcome between exposure and the development of asymptomatic group B streptococcal colonization or symptomatic group B streptococcal infection. Specifically, a high quantity of cell-associated sialic acid, and its elaboration in supernatant fluid at high concentrations, is associated with virulence. The unique capsular structures of group B streptococci might also enhance the invasiveness of one serotype over another.

Group B Streptococcus (S Agalactiae) Clinical Syndromes

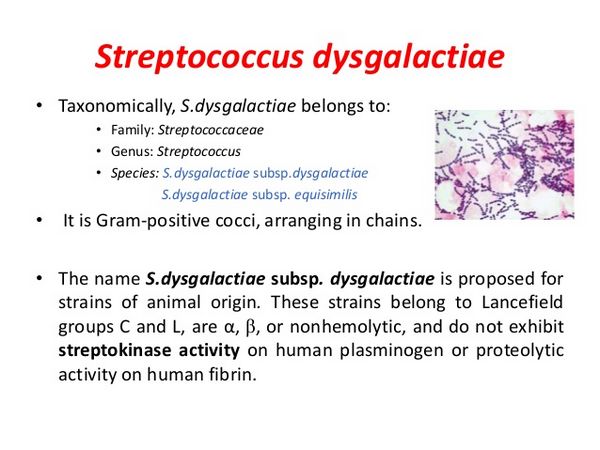

STREPTOCOCCUS DYSGALACTIAE SUBSPP. EQUISILIMIS & STREPTOCOCCUS ZOOEPIDEMICUS

Essentials of Diagnosis

- Associated with domestic animals.

- Formerly known as groups C and G streptococci.

- Pharyngitis, skin and soft tissue infections, and arthritis are common syndromes.

General Considerations

Epidemiology

S dysgalactiae subspp. equisimilis and S zooepidemicus have been isolated from the throat, nose, skin, and genital and intestinal tracts of asymptomatic carriers and from the umbilicus of as many as two-thirds of asymptomatic newborns. Domestic animals (eg, horses, cattle, pigs, and chickens) may be infected; epidemic infections have been noted in horses, cattle, sheep, and pigs. Many cases of human infection can be traced to an animal source.

Human infection has also been associated with consumption of homemade cheese and unpasteurized cow’s milk. Underlying conditions have been noted in most patients with S dysgalactiae subspp. equisimilis and S zooepidemicus infections. These include cardiopulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic dermatologic conditions, malignancy, immunosuppression, alcohol abuse, renal or hepatic insufficiency, and injection drug abuse. These streptococci also cause recurrent cellulitis at the saphenous vein donor site in patients who have undergone coronary artery bypass surgery.

Microbiology

S dysgalactiae subspp. equisimilis and S zooepidemicus include the organisms formerly known as groups C and G streptococci (S equisimilis, S equi, S zooepidemicus, S dysgalactiae, and S canis).

Streptococcus Dysgalactiae Subspp. Equisilimis & Streptococcus Zooepidemicus: Clinical Syndromes

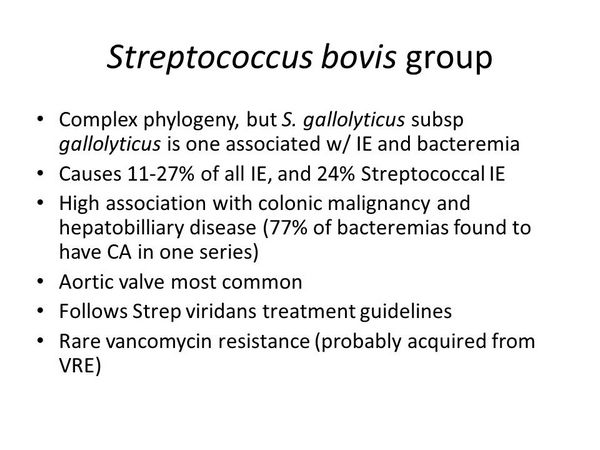

STREPTOCOCCUS BOVIS

Essentials of Diagnosis

- Grow in 40% bile, hydrolyze esculin.

- Do not grow in 6.5% sodium chloride.

- Pyrrolidonyl arylamidase reactivity negative.

General Considerations

Epidemiology

S bovis is a normal inhabitant of the gastrointestinal tract. S bovis bacteremia is highly associated with bacterial endocarditis as well as with underlying lesions of the colon, including malignancy. In some series, the prevalence of malignancy in patients with S bovis bacteremia exceeds 50%. As such, all patients with S bovis bacteremia should undergo a careful workup to exclude colonic neoplasms.

Microbiology

S bovis are group D streptococci and share properties in common with enterococci including the ability to grow in the presence of 40% bile and to hydrolyze esculin. A number of other tests, however, including growth in 6.5% sodium chloride and pyrrolidonyl arylamidase reactivity differentiate S bovis from enterococci.

CLINICAL SYNDROMES

S bovis causes bacteremia, endocarditis, urinary tract infection, meningitis, and neonatal sepsis (Box 1). The gastrointestinal tract is the usual portal of entry in cases of S bovis bacteremia although the hepatobiliary tree, urinary tract, and even dental procedures have been implicated as possible sources.

Diagnosis

Isolation of S bovis from typically sterile sites permits the clinical diagnosis of infection.

Treatment

S bovis is very susceptible to penicillin (MICs range from 0.01 to 0.12 ug/mL) (Box 2). Other effective agents include ampicillin, the antipseudomonal penicillins, ceftriaxone, erythromycin, clindamycin, and vancomycin. Penicillin alone given for 4 weeks is adequate to treat patients with S bovis endocarditis. Vancomycin is a reasonable alternative in penicillin-allergic patients. Bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis regimens are given in site and are relevant to S bovis endocarditis.

BOX 1. Major Gram-Positive Cocci Infections

Organisms

Syndromes

Viridans group streptococci (including Abiotropha spp.)

- Endocarditis

- Bacteremia, especially in febrile neutropenic patients

- Meningitis

- Other infections

Group B Streptococcus (Streptococcus agalactiae)

- Neonatal infection: bacteremia, pneumonia, meningitis, bone and joint infection

- Postpartum infection: bacteremia, endometritis, endoperimetritis

- Group B streptococcal infection in adults: pneumonia, endocarditis, arthritis, osteomyelitis, skin and soft tissue infections

S dysqalactiae subspp. equisimilis and S zooepidemicus

- Pharyngitis

- Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

- Cutaneous and subcutaneous infections

- Arthritis/osteomyelitis

- Endocarditis

S bovis

- Bacteremia

- Endocarditis

- Urinary tract infection

- Meningitis

- Neonatal sepsis

BOX 2. Treatment of Other Gram-Positive Cocci Infections 1,2

Viridans group streptococci (Penicillin MIC =0.12 µg/mL), group B streptococcus (S agalactiae), S dysgalactiae subspp. equisimilis, S zooepidemicus, and S bovis

First Choice

Penicillin G sodium 12-18 million U/24 h IV either continuously or in 6 divided doses

PLUS gentamicin sulfate 1 mg/kg IV/IM every 8 h

Second Choice

Ampicillin 1-2 g IV/IM every 4-6 h

Cefazolin 1 g IV/IM every 8 h

Cefotaxime 1-2 g IV/IM every 8 h

Ceftriaxone 1-2 g once daily IV/IM

Imipenem 500 mg IV/IM every 6 h

Vancomycin 30 mg/kg 24 h IV in 2 divided doses, not to exceed 2 g/24 h unless serum levels are monitored

Penicillin Allergic

Vancomycin 30 mg/kg 24 h IV in 2 divided doses not to exceed 2 g/24 h unless serum levels are monitored

Pediatric Considerations

Penicillin G IV/IM, 100,000-250,000 U/kg/24 h in divided doses every 4 h PLUS gentamicin 1 mg/kg IV/IM every 6 h

Ampicillin 100-200 mg/kg/24 h IV/IM in 4-6 divided doses

Vancomycin 10 mg/kg 6 h IV not to exceed 2 g/24 h unless serum levels are monitored

Ceftriaxone 50-100 mg/kg 24 h IV/IM not to exceed 4 g/24 h

Imipenem 12.5 mg/kg every 6 h IV/IM not to exceed 4 g/24 h

Cefazolin 25-100 mg/kg 24 h IV/IM in 3-4 divided doses

Cefotaxime 50-180 mg/kg 24 h IV/IM in 4-6 divided doses

1Doses provided assuming normal renal function.

2Oral alternatives may be appropriate for nonsevere infections with these organisms.

BOX 3. Prevention and Control of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease

Screening Approach

- All pregnant women should be screened at 35- to 37-week gestation for group B streptococcal carriage.

- All identified carriers and women who deliver preterm before a culture result is available should be offered intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis (see below).

Nonscreening Approach

Intrapartum antimicrobial agents should be offered to women with risk factors (eg, those with elevated intrapartum temperature, membrane rupture = 18 h, premature onset of labor or rupture of membranes at < 37 wks): Ampicillin 2 g IV every 4-6 h (until delivery), or penicillin G 5 million U IV every 8 h (until delivery). In penicillin-allergic patients, use clindamycin IV or erythromycin IV until delivery.

BOX 4. Rare Gram-Positive Cocci Infections

Organisms

Syndromes

Streptococcus iniae

- Cellulitis

- Bactermeia

- Endocarditis

- Meningitis

- Septic arthritis

Leuconostoc spp.

- Bacteremia

- Line sepsis

- Meningitis

- Dental abscess

Pediococcus spp.

- Bacteremia

Stomatococcus mucilaginosus

- Endocarditis

- Bacteremia in febrile neutropenic patients

- Line sepsis

- Meningitis

- Peritonitis

Aerococcus spp.

- Endocarditis

- Bacteremia

- Urinary tract infection

Gemella spp.

- Endocarditis

- Meningitis

- Arthritis

- Bacteremia

- Urinary tract infection

- Wound infection

Alloiococcus otitis

- Otitis media (possible association)

Micrococcus spp.

- Endocarditis

Lactococcus spp.

- Endocarditis

Globicatella spp.

- Bacteremia

- Urinary tract infection

- Meningitis

Helcococcus kunzii

- Wound infection (possible association)