Staphylococci (both S aureus and CoNS) have emerged as the two most common organisms cultured from patients with primary bloodstream infections. The term “primary bacteremia” refers to positive blood cultures without an identifiable anatomic focus of infection. Differentiation of primary bacteremia from infective endocarditis (IE), in which infection of the cardiac valves leads to continuous bacterial seeding of the bloodstream, may challenge even the most experienced clinician.

Primary S aureus bacteremia is associated with insulin-dependent diabetes, the presence of a vascular graft, and, most significantly, the presence of an indwelling intravascular catheter. Risk factors for IE include structurally abnormal valves, recent injection drug use, and the presence of a prosthetic cardiac valve.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with primary S aureus bacteremia are systemically ill, with fever, chills, malaise, and hypotension. S aureus endocarditis is usually an acute disease, with a presentation indistinguishable from S aureus bacteremia. For the most part, patients lack the classic cutaneous stigmata associated with subacute bacterial endocarditis (Box 4). A new or changed cardiac murmur, or evidence of embolic disease, in the setting of S aureus bacteremia strongly supports the diagnosis of IE. Endocarditis in injection drug users involves the tricuspid valve in 75% of cases, and respiratory complaints, attributable to septic pulmonary embolization with infarction, predominate.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings in primary bacteremia and IE are nonspecific; an elevated WBC count is the most common abnormality. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which is elevated in subacute IE, may be normal. Because endocarditis causes continuous seeding of the bloodstream, it is common to see “high-grade” bacteremia, with multiple positive blood cultures from different venous sites drawn at disparate time intervals.

Imaging

The classic radiographic finding in patients with right-sided endocarditis is the presence of multiple pleural-based densities (so-called “cannon-ball lesions”) caused by septic pulmonary emboli. Radiologic signs with left-sided disease are manifestations of congestive heart failure, ranging from increased interstitial markings to parenchymal opacification from pulmonary edema.

Differential Diagnosis

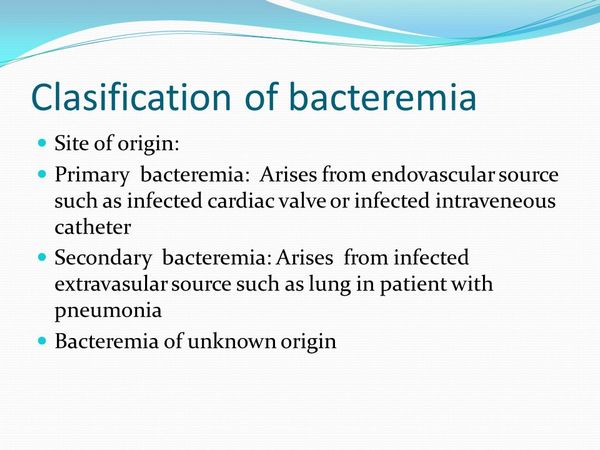

Culture of S aureus from the blood should prompt a thorough search for an infected primary focus. Common local infections predisposing to secondary bacteremia include infections of indwelling intravenous catheters or other prosthetic material, postoperative wound infections, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and cellulitis. In the absence of an identifiable anatomic focus of infection, the clinician must differentiate primary bacteremia from infective endocarditis.

Complications

Complications of S aureus bacteremia are primarily from bacterial seeding of the viscera, with subsequent end-organ infections such as endocarditis (a sequela of uncomplicated bacteremia in 5-10% of cases), osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, cerebral abscess, and perinephric abscess. Mortality with primary bacteremia ranges from 25% to 40%. Factors associated with a fatal outcome include the absence of a removable source of infection (such as an intravenous line), age > 60 years, and underlying pulmonary disease.

Morbidity in left-sided IE is due to progressive valve destruction or embolic phenomena. Valve failure results in congestive heart failure, which may be insidious or may present as acute pulmonary edema following rupture of the chordae tendineae. New-onset heart block is the earliest sign of a myocardial ring abscess. Recurrent systemic emboli on appropriate therapy or persistent bacteremia are indications for surgical valve replacement. The mortality rate for left-sided IE ranges from 20% to 44%, as compared with < 5% for right-sided disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiating primary bacteremia from IE causing continuous intravascular seeding is often difficult: the probability that blood cultures growing S aureus represent IE varies from 10% to 40%, depending on the population studied. The distinction between these two syndromes is important as IE requires prolonged therapy and carries a worse prognosis.

Several sets of diagnostic criteria for IE have been proposed. The most sensitive is the Duke Criteria, which incorporates echocardiogram findings with clinical factors to stratify the risk of IE. Patients with community-acquired S aureus bacteremia or nosocomially acquired cases with known cardiac valvular disease or prosthetic valves have the highest probability of having IE and should be evaluated for cardiac involvement with a transthoracic echocardiogram.

Treatment

Optimal empiric treatment for primary bloodstream infection is based on the likelihood that an organism is resistant to methicillin (defined as an MIC = 8 ug/ml). Penicillinase-resistant semisynthetic penicillins (PRSP) such as oxacillin or nafcillin are the recommended agents for community-acquired infections, or nosocomial infections in institutions with documented low prevalence rates for MRSA. In facilities with significant isolation rates for MRSA, empiric treatment with vancomycin is indicated. A PRSP should be substituted as soon as the bacteria is proven susceptible, as vancomycin is less active against S aureus, and patients treated with this agent have longer duration of fever and bacteremia. Regardless of which agent is used, treatment for uncomplicated bacteremia should be continued 10-14 days.

Bacteremia attributed to an infected indwelling central venous catheter is difficult to eradicate without removal of the foreign body. Subcutaneous infection along the catheter tunnel, hemodynamic instability, fever or rigors more than 48 hours after initiating antibiotic treatment, persistently positive blood cultures, or septic venous thrombophlebitis mandate prompt catheter removal.

Therapy for IE is guided by the clinical scenario (Box 5). Patients with uncomplicated, right-sided, methicillin-sensitive S aureus endocarditis respond to 2 weeks of treatment. Extrapulmonary embolic disease, persistent symptoms or bacteremia after more than 96 hours of therapy, high-level aminoglycoside resistance, or concurrent left-sided valvular involvement require a full course of therapy, lasting 4-6 weeks.

Aminoglycosides act synergistically with beta-lactams against staphylococci; their use reduces the time to clearing of the bacteria from the bloodstream, although they do not affect mortality rates in IE. Synergy occurs at relatively low doses of aminoglycosides, with optimal peak and trough levels for gentamicin 3.0 and 0.5 um/mL, respectively.

The penicillin allergic patient with IE presents a treatment challenge. For patients without a history of immediate-type hypersensitivity, a first-generation cephalosporin is the preferred agent. Patients with a history of anaphylaxis or other severe penicillin allergy should receive vancomycin. The potential for antagonism between vancomycin and rifampin exists, and adjuvant therapy with rifampin should be reserved for patients failing monotherapy.