Essentials of Diagnosis

- Pharyngitis: presence of sore throat, submandibular adenopathy, fever, pharyngeal erythema, exudates.

- Rheumatic fever: migratory arthritis, carditis, Syndenham’s chorea, pharyngitis.

- Cellulitis: pink skin, fever, tenderness, swelling.

- Scarlet fever: sandpaper-like erythema, strawberry tongue, streptococcal pharyngitis or skin infection, high fever.

- Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis: acute glomerulonephritis (hematuria, proteinuria) following pharyngitis or impetigo.

- Impetigo: dry, crusted lesions of the skin, weeping golden-colored fluid.

- Erysipelas: salmon red rash of face or extremity, well-demarcated border, fever, occasionally bullous lesions.

- Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: isolation of Group A streptococcus from a normally sterile site, sudden onset of shock and organ failure.

- Necrotizing fasciitis, myonecrosis: deep, severe pain, fever, purple bullae shock, tissue destruction of fascia or muscle, organ failure.

General Considerations

Epidemiology

Streptococcus pyogenes is a human pathogen without an animal reservoir. Group A streptococci (GAS) cause most streptococcal disease, but other groups are important pathogens in some settings (Box 1). Group A streptococcal infections have the highest incidence in children younger than age 10. The asymptomatic prevalence is also higher (15-20%) in children, compared with that in adults (<5%). Age is not the only factor; crowded conditions in temperate climates during the winter months are associated with epidemics of pharyngitis in school children as well as military recruits. Impetigo is most common in children from ages 2 to 5 and generally occurs in the summer in temperate climates and year-round in tropical areas .

Similarly, 90% of cases of scarlet fever occur in children 2 to 8 years old, and, like pharyngitis, it is most common in temperate regions during the winter months. An experiment of nature in the Faroe Islands suggested that susceptibility to scarlet fever is not dependent on young age per se. Scarlet fever had disappeared from that isolated island for several decades until it was reintroduced by a visitor with unsuspected scarlet fever. An epidemic of scarlet fever ensued, with significant attack rates in all age groups, suggesting that other factors (such as the lack of protective antibody against scarlatina toxin or the introduction of a new strain) rather than age, predisposed those individuals to clinical illness.

In contrast to pharyngitis, impetigo, and scarlet fever, bacteremia has had the highest age-specific attack rate in the elderly and in neonates. Between 1986 and 1988, the prevalence of bacteremia increased 800-1000% in adolescents and adults in Western countries. Although some of this increase is attributable to IV drug abuse and puerperal sepsis, most of the increase is owing to cases of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (strepTSS).

Human mucus membranes and skin serve as the natural reservoirs of Streptococcus pyogenes. Pharyngeal and cutaneous acquisition is spread person to person via aerosolized microdroplets and direct contact, respectively. Epidemics of pharyngitis and scarlet fever have also resulted from ingestion of contaminated nonpasteurized milk or food. Epidemics of impetigo have been reported, in tropical areas, day care centers, and among underprivileged children. Group A streptococcal infections in hospitalized patients occur during child delivery (puerperal sepsis), times of war (epidemic gangrene), surgical convalescence (surgical wound infection, surgical scarlet fever), or as a result of burns (burn wound sepsis). Thus, in most clinical streptococcal infections, the mode of transmission and portal of entry are easily ascertained. In contrast, among patients with strepTSS, the portal of entry is obvious in only 50% of cases.

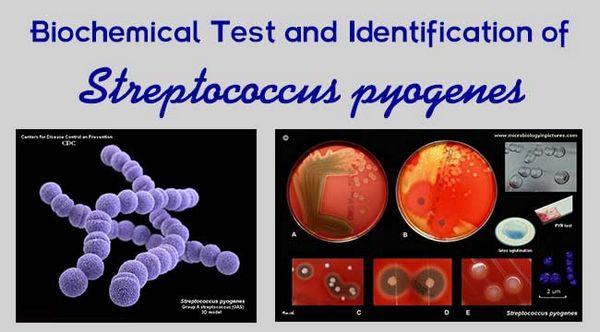

Microbiology

Streptococci are gram-positive coccoid bacteria that grow in chains. Streptococci colonize the mucus membranes of animals, produce catalase, and may be aerobic, anaerobic, or facultative. Streptococci require complex media containing blood products for optimal growth. On blood agar plates, streptococci may cause complete (B), incomplete (A), or no hemolysis (C). The exhaustive work of Rebecca Lancefield has allowed hemolytic streptococci to be classified into Groups A through O based on acid extractable antigens of cell wall material. The availability of rapid latex agglutination kits provides even small clinical laboratories the means to identify streptococci according to Lancefield’s grouping. Bacitracin susceptibility, bile esculin hydrolysis, and the CAMP test (flame-type synergistic hemolysis on a Staphylococcus aureus blood agar streak) are useful presumptive tests for classifying Groups A, D, or B streptococci, respectively. Modern schemes of classification of hemolytic and nonhemolytic streptococci use complex biochemical and genetic techniques.

Pathogenesis

Complex interactions between host epithelium and streptococcal factors such as M-protein, lipoteichoic acid components, and fimbriae are necessary for adherence. Fibronectin-binding protein (protein F) also contributes to adherence since protein F-deficient mutants are incapable of binding to epithelial cells.

Within the tissues, streptococci may evade opsonphagocytosis by destroying or inactivating complement-derived chemoattractants and opsonins (C5a peptidase) and by binding immunoglobulins. Expression of M-protein, in the absence of type-specific antibody, also protects the organism from phagocytosis by polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes.

Bacterial Cell Structure & Extracellular Products

Capsule

Some strains of S pyogenes possess luxuriant capsules of hyaluronic acid, resulting in large mucoid colonies on blood agar. Luxuriant production of M-protein may also impart a mucoid colony morphology, and this trait has been associated with M-18.

Cell wall

The cell wall is composed of a peptidoglycan backbone with integral lipoteichoic acid components. The function of lipoteichoic acid components is not well known; however, both peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid components have important interactions with the host.

M-proteins

Over 80 different M-protein types of Group A streptococci are currently described. M-protein also protects the organism against phagocytosis by polymorphonuclear leukocytes, although this property can be overcome by type-specific antisera.

Streptolysin O

Streptolysin O belongs to a family of oxygen-labile, thiol-activated cytolysins and causes the broad zone of ß hemolysis surrounding colonies of S pyogenes on blood agar plates. Thiol-activated cytolysin toxins bind to cholesterol on eukaryotic cell membranes, creating toxin-cholesterol aggregates that contribute to cell lysis via a colloid-osmotic mechanism. In situations in which serum cholesterol is high, ie, nephrotic syndrome, falsely elevated anti-streptolysin O antibody (ASO) titers may occur because both cholesterol and anti-ASO antibodies will “neutralize Streptolysin O.” Striking amino acid homology exists between Streptolysin O and other thiol-activated cytolysin toxins.

Streptolysin S

Streptolysin S is a cell-associated hemolysin and does not diffuse into the agar media. Purification and characterization of this protein have been difficult, and its only role in pathogenesis may be in direct or contact cytotoxicity.

Deoxyribonucleases A, B, C, and D

Expression of deoxyribonucleases (DNases) in vivo elicits production of anti-DNase antibody following both pharyngeal and skin infection; this is most true for DNase B with Group A streptococci.

Hyaluronidase

This extracellular enzyme hydrolyses hyaluronic acid in deeper tissues, facilitating the spread of infection along fascial planes. Antihyaluronidase titers rise following S pyogenes infections, especially those involving the skin.

Pyrogenic exotoxins

Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins types A, B, and C, also called scarlatina or erythrogenic toxins, induce lymphocyte blastogenesis, potentiate endotoxin-induced shock, induce fever, suppress antibody synthesis, and act as superantigens. The identification of these three different types of pyrogenic exotoxins may in part explain why some individuals may have multiple attacks of scarlet fever.

Although all strains of Group A streptococci are endowed with genes for streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B, not all strains produce it, and even among producing strains, the quantity of toxin synthesized varies greatly from strain to strain.

Pyrogenic exotoxin C, like streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A, is bacteriophage-mediated, and expression is likewise highly variable. Recently, mild cases of scarlet fever in England and the United States have been associated with streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin C positive strains.

Other superantigens

Two new superantigens, mitogenic factor and streptococcal superantigen, have recently been described; however, their roles in pathogenesis have not been fully investigated.

CLINICAL SYNDROMES

PHARYNGITIS & THE ASYMPTOMATIC CARRIER

Clinical Findings

Patients with streptococcal pharyngitis have abrupt onset of sore throat, submandibular adenopathy, fever, and chilliness but usually not frank rigors. Cough and hoarseness are rare, but pain on swallowing is characteristic. The uvula is edematous, the tonsils are hypertrophied, and the pharynx is erythematous with exudates, which may be punctate or confluent. Acute pharyngitis is sufficient to induce antibody against M-protein, Streptolysin O, DNase and hyaluronidase, and, if present, pyrogenic exotoxins. Depending on the infecting strain, pharyngitis may progress to scarlet fever, bacteremia, suppurative head and neck infections, rheumatic fever, post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, or strepTSS. Pharyngitis is usually self-limited and pain, swelling, and fever resolve spontaneously in 3-4 days even without treatment (Boxes 2 and 3).

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis is difficult when based only on clinical parameters, especially in infants, among which rhinorrhea may be the dominant manifestation. Even in older children with all of the above physical findings, the correct clinical diagnosis is made in only 75% of patients. Absence of any one of the classic signs greatly reduces the specificity. Rapid antigen detection tests in the office setting have a sensitivity and specificity of 40-90%. A popular approach in clinical practice is to obtain two throat swab samples from the posterior pharynx or tonsillar surface. A rapid strep test is performed on the first, and, if positive, the patient is treated with antibiotics and the second swab discarded. If the rapid strep test is negative, the second is sent for culture, and treatment is withheld, pending a positive culture.

SCARLET FEVER

During the last 30-40 years, outbreaks of scarlet fever in the Western world have been infrequent and notably mild, and the illness has been referred to as pharyngitis with a rash or benign scarlet fever (Table 1). In contrast, in the latter half of the 19th century, mortalities of 25-35% were common in the United States, Western Europe, and Scandinavia. The fatal or malignant forms of scarlet fever have been described as either septic or toxic. Septic scarlet fever refers to patients who develop local invasion of the soft tissues of the neck and complications such as upper-airway obstruction, otitis media with perforation, meningitis, mastoiditis, invasion of the jugular vein or carotid artery, and bronchopneumonia.

Toxic scarlet fever is rare today, but, historically, patients initially developed severe sore throat, marked fever, delirium, skin rash, and painful cervical lymph nodes. In severe toxic cases, fevers of 107°F, pulses of 130-160 beats per minute, severe headache, delirium, convulsions, little if any skin rash, and death within 24 hours were common. These cases occurred before the advent of antibiotics, antipyretics, and anticonvulsants, and deaths were acutely the result of uncontrolled seizures and hyperpyrexia. In contrast, children with septic scarlet fever had prolonged courses and succumbed 2-3 weeks after the onset of pharyngitis. Complications of streptococcal pharyngitis and malignant forms of scarlet fever have been less common in the antibiotic era. Even before antibiotics became available, necrotizing fasciitis and myositis were not described in association with scarlet fever.

STREPTOCOCCAL PYODERMA (Impetigo contagiosa)

Impetigo is most common in patients with poor hygiene or malnutrition. Colonization of the unbroken skin occurs first, then intradermal inoculation is initiated by minor abrasions, insect bites, etc. Single or multiple thick-crusted, golden-yellow lesions develop within 10-14 days. Penicillin orally or parenterally, or bacitracin or mupiricin topically, are effective treatments for impetigo and also reduce transmission of streptococci to susceptible individuals (see Box 2). None of these treatments, including penicillin, prevents post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis.

ERYSIPELAS

Erysipelas is caused exclusively by S pyogenes and is characterized by an abrupt onset of fiery red swelling of the face or extremities. Distinctive features are well-defined margins, particularly along the nasolabial fold, scarlet or salmon red rash, rapid progression, and intense pain. Flaccid bullae may develop during the second to third day of illness, yet extension to deeper soft tissues is rare. Surgical debridement is not necessary, and treatment with penicillin is effective (Box 4). Swelling may progress despite treatment, although fever, pain, and the intense redness diminish. Desquamation of the involved skin occurs 5-10 days into the illness. Infants and elderly adults are most commonly afflicted, and, historically, erysipelas, like scarlet fever, was more severe before the turn of the century.

CELLULITIS

Group A streptococci are the most common cause of cellulitis; however, alternative diagnoses may be obvious when associated with a primary focus, such as an abscess or boil (Staphylococcus aureus), dog bite (Capnocytophagia), cat bite (Pasteurella multocida), freshwater injury (Aeromonas hydrophila), seawater injury (Vibrio vulnifica), animal carcasses, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathia, and so on. Clinical clues to the etiologic diagnosis are important because aspiration of the leading edge and punch biopsy yield a causative organism in only 15% and 40% of cases, respectively. Patients with lymphedema of any cause, such as lymphoma, filariasis, or postsurgical regional lymph node dissection (eg, mastectomy, carcinoma of the prostate), are predisposed to developing streptococcal cellulitis, as are patients with chronic venous stasis. Recently, recurrent saphenous vein donor site cellulitis has been attributed to Group A, C, or G streptococci.

Group A streptococci may invade the epidermis and subcutaneous tissues, resulting in local swelling, erythema, and pain. The skin becomes indurated and, unlike the brilliant redness of erysipelas, is a pinkish color. If fever, pain, or swelling increase, if bluish or violet bullae or discoloration appear, or if signs of systemic toxicity develop, a deeper infection, such as necrotizing fasciitis or myositis, should be considered (see below). An elevated serum creatinine phosphokinase suggests deeper infection, and prompt surgical inspection and debridement should be performed (see Box 4).

LYMPHANGITIS

Cutaneous infection with bright red streaks ascending proximally is invariably caused by Group A streptococcus. Prompt parenteral antibiotic treatment is mandatory since bacteremia and systemic toxicity develop rapidly once streptococci reach the bloodstream via the thoracic duct.

NECROTIZING FASCIITIS

Necrotizing fasciitis, originally called streptococcal gangrene, is a deep-seated infection of the subcutaneous tissue that results in progressive destruction of fascia and fat but may spare the skin itself. Necrotizing fasciitis has become the preferred term since Clostridium perfringens, Clostridium septicum, and S aureus can produce a similar pathologic process. Infection may begin at the site of trivial or unapparent trauma. Within the first 24 hours, swelling, heat, erythema, and tenderness develop and rapidly spread proximally and distally from the original focus.

During the next 24-48 hours, the erythema darkens, changing from red to purple and then to blue, and blisters and bullae form that contain clear yellow fluid. On the fourth or fifth day, the purple areas become frankly gangrenous. From the seventh to the tenth day, the line of demarcation becomes sharply defined, and the dead skin begins to reveal extensive necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue. Patients become increasingly prostrated and emaciated and may become unresponsive, mentally cloudy, or even delirious. Historically, aggressive fasciotomy and debridement (bearclaw fasciotomy) and irrigations with Dakan’s solution (hypochlorous acid) achieved mortalities as low as 20%, even before antibiotics were available (Box 5). The time course of progression of necrotizing fasciitis is more rapid, and mortalities have been higher in the 1980-1990s, suggesting increased virulence of streptococci.

MYOSITIS

Historically, streptococcal myositis has been an extremely uncommon infection, only 21 cases being documented from 1900 to 1985. Recently, the prevalence of streptococcal myositis has increased in the United States, Norway, and Sweden. Translocation of streptococci from the pharynx to the deep site of trauma (muscle) likely occurs hematogenously. Symptomatic pharyngitis or penetrating trauma is uncommon. Severe pain may be the only presenting symptom; swelling and erythema may be the only signs of infection. In most cases, a single muscle group is involved; however, because patients are frequently bacteremic, multiple sites of myositis or abscess can occur.

Distinguishing streptococcal myositis from spontaneous gas gangrene caused by C perfringens or C septicum may be difficult, although the presence of crepitus or gas in the tissue would favor clostridial infection. Myositis is easily distinguished from necrotizing fasciitis anatomically by surgical exploration or incisional biopsy, although clinical features of both conditions overlap and both necrotizing fasciitis and myonecrosis may occur together.

In published reports, the case-fatality rate of necrotizing fasciitis is between 20 and 50%, whereas that of streptococcal myositis is between 80 and 100%. Aggressive surgical debridement is extremely important because of the poor efficacy of penicillin described in human cases as well as in experimental models of streptococcal myositis (see Box 5).

PNEUMONIA

Pneumonia caused by Group A streptococcus is most common in women in the second and third decades of life and causes large pleural effusions and empyema. Several liters of pleural fluid may accumulate within hours. Chest tube drainage is mandatory, although management is complicated by multiple loculations and fibrinous effusions, resulting in restrictive lung disease.

Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome

BOX 1. Streptococcal Infections

Adults

Children

More Common

- Cellulitis

- Erysipelas

- Bacteremia

- Necrotizing fasciitis

- Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome

- Pharyngitis

- Scarlet fever

- Impetigo

- Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

- Rheumatic fever

- Bacteremia (neonates)

Less Common

- Pharyngitis

- Scarlet fever

Impetigo (homeless)

- Erysipelas

- Streptococccal toxic shock syndrome

- Necrotizing fasciitis, except after chickenpox

BOX 2. Treatment of Impetigo

Children

Adults

First Choice <60 lbs:

Benzathine penicillin, 600,000 U IM >60 lbs:

Benzathine penicillin, 1.2 million U IM

Second Choice <60 lbs:

Penicillin G or V, 200,000 units (125 mg) QID × 10 days >60 lbs:

Penicillin G or V, 400,000 U (250 mg) QID × 10 days

Options for Penicillin-Allergic Patients

Erythromycin ethylsuccinate, 40-50 mg/kg QID × 10 days PO2

Erythromycin ethylsuccinate, 40-50 mg/kg QID × 10 days PO2

- Topical agents such as bacitracin or mupirocin ointment may be useful in limiting the spread of impetigo to other children or family members.

- Oral cephalosporins, such as cefalexin, cephradine, cefadroxil, cefaclor, cefixime, cefuroxime, cefpodoxime, and cefdinir, given orally for 10 days, are also good alternatives to erythromycin in penicillin-allergic patients.

BOX 3. Treatment of Recurrent Streptococcal Pharyngitis and Tonsillitis

Children

Adults

First Choice <60 lbs:

Benzathine penicillin, 600,000 U IM >60 lbs:

Benzathine penicillin, 1.2 million U IM

Second Choice

Ampicillin plus clavulinic acid, 20-40 mg/kg/day, PO (may require IV treatment)

Ampicillin plus clavulinic acid, 20-40 mg/kg/ day, PO (may require IV treatment)

Options for Penicillin-Allergic Patients

Clindamycin, 10 mg/kg/day, PO

Clindamycin, 10 mg/kg/day, PO

BOX 4. Treatment of Cellulitis and Erysipelas

Children

Adults

First Choice <60 lbs:

Penicillin G or V, 200,000 U (125 mg) QID × 10 days >60 lbs:

Penicillin G or V, 400,000 U (250 mg) QID × 10 days

Second Choice <60 lbs:

Dicloxacillin, 125 mg QID × 10 days >60 lbs:

Dicloxacillin, 250-500 mg QID × 10 days

Options for Penicillin-Allergic Patients

Erythromycin ethylsuccinate, 40-50 mg/kg QID × 10 days PO1

Erythromycin ethylsuccinate, 40-50 mg/kg QID × 10 days PO1

- Oral cephalosporins, such as cefalexin, cephradine, cefadroxil, cefaclor, cefixime, cefuroxime, cefpodoxime, and cefdinir, given orally for 10 days, are good alternatives to erythromycin in penicillin-allergic patients.

BOX 5. Treatment of Necrotizing Fasciitis/Myositis and Streptococcal TSS

Children

Adults

First Choice

Penicillin G, 250,000 U/kg/d in 4-6 divided doses IV, PLUS clindamycin, 25-40 mg IV in 3-4 divided doses

Clindamycin, 1800-2100 mg q 24 hours, IV, in 3-4 divided doses, PLUS penicillin G, 2 million U q 4 hours, IV1

Options for Penicillin-Allergic Patients

Clindamycin, see above

Clindamycin, see above

- Good in vitro activity but not as effective as clindamycin in animal models of necrotizing fasciitis/myositis caused by Group A streptococci.

BOX 6. Prophylaxis for Rheumatic Fever

Children

Adults

First Choice <60 lbs:

Benzathine penicillin, 600,000 units IM, once per month >60 lbs:

Benzathine penicillin, 1.2 million units IM, once per month

Second Choice

Phenoxomethyl penicillin, 250 mg q day, PO

Phenoxomethyl penicillin, 250 mg q day, PO

Options for Penicillin-Allergic Patients

Erythromycin 250 mg/day, PO1 OR <60 lbs: sulfadizine orally, 0.5 gm/day

Erythromycin 250 mg/day QID × 10 days PO1 OR >60 lbs: sulfadizine, 1 gm/day

- Oral cephalosporins, such as cefalexin, cephradine, cefadroxil, cefaclor, cefixime, cefuroxime, cefpodoxime, and cefdinir, given orally for 10 days, are good alternatives to erythromycin in penicillin-allergic patients.