Essentials of Diagnosis

- Spiral, motile, coil-shaped, elongated (0.10 um × 5-20 um) spirochete.

- No reliable method for sustained in vitro cultivation.

- Direct detection with darkfield microscopy or immunofluorescent antibody in early syphilis.

- Nontreponemal antibody tests (rapid plasma reagin, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL]) for screening, treatment follow-up.

- Treponema-specific antibody tests (fluorescent treponemal antibody test, microhemagglutination-T pallidum test) for confirmation.

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) lymphocytosis, elevated CSF protein, or reactive CSF VDRL test suggests neurosyphilis.

- PCR, DNA probes, and immunoblotting techniques promising in congenital syphilis, early syphilis, or neurosyphilis.

- All patients with T pallidum infection should be tested for HIV coinfection and vice versa.

General Considerations

The term syphilis was first used in 1530 by the Italian physician Girolamo Fracastoro in his epic poem Syphilis Sive Morbus Gallicus. Much has been learned since then about this sexually transmitted disease caused by T pallidum. Public health screening programs and the introduction of antibiotics led to a marked decline in the number of new cases of syphilis in the United States after World War II.

However, the advent of AIDS was associated with an increase in new cases of syphilis, necessitating the reeducation of health care personnel in the evaluation and management of this disease.

Epidemiology

Genital herpes and syphilis are the most common causes of genital ulcerations in patients presenting to sexually transmitted disease clinics in the United States. Syphilis is usually transmitted by sexual contact with the infectious lesions of primary and secondary syphilis. Syphilis develops in ~ 30-60% of sexual contacts of individuals with infectious syphilis. Syphilis is less commonly transmitted in utero or by means of blood transfusion, nongenital body contact, and accidental direct inoculation.

The incidence of primary and secondary syphilis (called early syphilis) reached a nadir in 1956 and then increased slowly. Two “epidemics” of early syphilis in the past 20 years have highlighted the role of human behavior in syphilis epidemiology: one peaked in 1982 and primarily involved bisexual and homosexual men; the second peaked in 1990 when 50,223 new cases of primary and secondary syphilis were reported.

This epidemic was associated with crack cocaine use and its effects on sexual behavior and disproportionately involved African Americans. The incidence of this outbreak was highest in the southern United States and in the nation’s large metropolitan areas. The incidence of congenital syphilis also rose from 4.3 cases/100,000 live births in 1983 to 107 cases/100,000 births in 1991, a change attributed to the increase in primary and secondary syphilis among women, more active surveillance, and the adoption of a more sensitive case definition for congenital syphilis in 1988-1989.

The incidence of all stages of syphilis including congenital syphilis has decreased since 1991. The number of new cases of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States in 1997 was 8,500, an incidence of 3.2 cases/100,000 persons, the lowest rate since 1941. In 1997, the incidence of congenital syphilis was 27 cases/100,000 live births, the lowest rate since the change in the surveillance case definition.

Microbiology

The order Spirochaetales and family Spirochaetaceae include human pathogens within the three genera, Treponema, Leptospira, and Borrelia. T pallidum subspecies pallidum is the causative agent of syphilis and is transmitted primarily through sexual contact. Nonvenereally transmitted treponemal infections include those caused by T carateum (pinta), T pallidum subspecies pertenue (yaws), and T pallidum subspecies endemicum (bejel or endemic syphilis). Clinical and epidemiological characteristics are used to distinguish among these treponemal infections because of the similarities in serologic host responses, microbial morphology, and antigenic composition. No currently available nucleic acid-based test reliably differentiates between the subspecies of T pallidum.

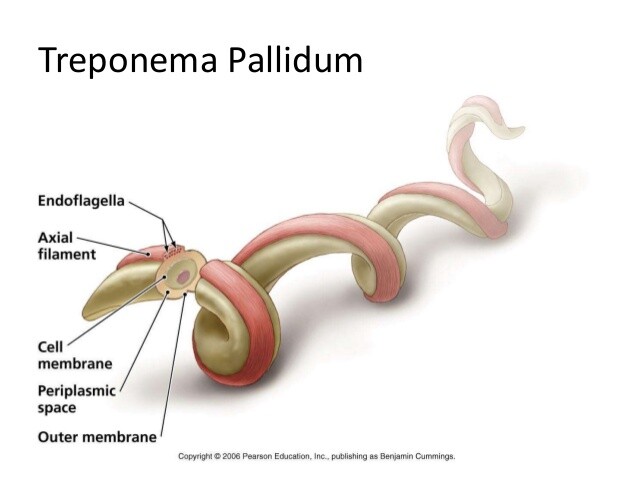

T pallidum is a microaerophilic spirochete that is tightly wound into a spiral shape, measuring 5-20 um in length and 0.1-0.2 um in width. With the ability to bend along its long axis, active motility is achieved with “corkscrewlike” motions. These organisms, too slender to be seen with light microscopy, can be readily visualized by darkfield microscopy, by direct immunofluorescent staining, or by silver staining.

This agent has resisted characterization because it cannot be sustained by in vitro culture methods. Instead, it requires rabbit or guinea pig inoculation for laboratory propagation. The organism is surrounded by an outer membrane consisting primarily of phospholipids and a low concentration of membrane proteins, a characteristic that when coupled with the organism’s slow multiplication time may explain its ability to persist in the infected host. Examination of the full 1.14-Mbp genome sequence of T pallidum reveals a large family of duplicated genes that are predicted to encode outer membrane porins and adhesins. These genes may reflect a mechanism for antigenic variation as well as targets for vaccine-induced immunity.

Axial filaments, or endoflagella, are attached to each end of the organism in the periplasmic space and mediate host cell adherence and motility. Recent investigations suggest that a sensory transducing chemotaxis protein may modulate this flagella-associated motility. The organism also contains a peptidoglycan layer and is susceptible to ß-lactam agents such as penicillin. Replication of this organism occurs by transverse fission.

Pathogenesis

T pallidum gains access to subepithelial tissues through microperforations in the skin or intact mucous membranes. A visible localized reaction occurs at the site of inoculation after 10-90 days, a reflection of the slow dividing time of this organism. This reaction takes the form of a papule before ulcerating to form the classic lesion of primary syphilis, the chancre.

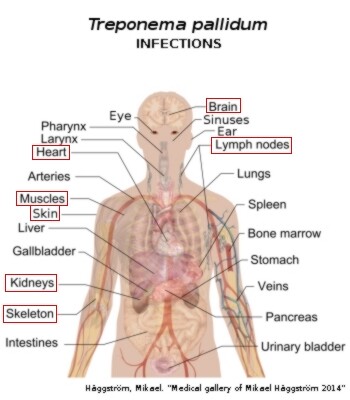

Histopathologic examination reveals perivascular inflammation consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Spirochetes also disseminate to regional lymph nodes and enter the bloodstream during this stage. The chancre usually heals spontaneously within 1-8 weeks, likely because of the phagocytosis of treponemes by macrophages. The secondary stage of infection begins ~ 6-10 weeks after the disappearance of the chancre. Spirochetemia is at its greatest level during this stage, despite a vigorous humoral immune response, and patients often present with constitutional complaints of malaise, fever, weight loss, and generalized lymphadenopathy.

Most patients develop skin and mucous membrane lesions. The lesions of both primary and secondary syphilis are highly infectious. The resolution of the signs and symptoms of untreated secondary syphilis heralds the beginning of the latent stage of infection, a clinically asymptomatic stage belied only by a positive treponemal serology. This phase is divided into an early latent stage, that is, the first year after infection, and the late latent stage. Approximately one-third of untreated patients with latent infection will go on to develop manifestations of late (or tertiary) disease after an indeterminate period of time.

Destructive tissue lesions of the tertiary stage of infection involve the skin and bone (leading to a gumma), the aorta, and the central nervous system (CNS). Histopathologic examination of these lesions reveals the characteristic obliterative endarteritis seen in other stages of syphilis. The lesions of late syphilis contain few visible spirochetes, suggesting a role for a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to T pallidum.

Much of the information regarding the natural course of untreated syphilis was obtained from two reports including the Oslo Study of untreated Norwegian patients diagnosed with early syphilis (1890-1951), and the Tuskegee Study, initiated by the United States Public Health Service (U.S. PHS) in 1932. This prospective study of ~ 400 black men with untreated latent syphilis in Macon County, Alabama, was terminated in 1972.

LATENT SYPHILIS

Clinical Findings

The manifestations of primary and secondary syphilis resolve without therapy, and the ensuing clinically silent phase of infection known as the latent stage is characterized by positive serologies and normal CSF (see Box 1). Patients can relapse with manifestations of secondary syphilis during this stage, usually during the early latent period. Asymptomatic infection lasting greater than one year, late latent syphilis, persists for the remainder of life in approximately two-thirds of untreated patients. The other one-third of patients develops symptomatic disease, ie, late syphilis.

Late Syphilis

CONGENITAL SYPHILIS

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Most infants acquire congenital syphilis from the transplacental dissemination of maternal T pallidum after the 16th week of gestation and less commonly from contact with an infectious lesion during the time of delivery (Box 2). The likelihood of fetal infection is inversely related to the duration of time that the mother has been infected; the risk of fetal transmission declines from 70-100% during early syphilis to 10-30% during latent disease. Congenital infections can be prevented by the appropriate identification and treatment of infected pregnant women. In 1988, the Centers for Disease Control increased the sensitivity of the congenital syphilis case definition by including all infants, symptomatic and asymptomatic, born to mothers with untreated or inadequately treated syphilis.

Congenital syphilis is divided into an early stage and a late stage. The early stage, seen primarily in infants 2-25 weeks of age, may be asymptomatic or may be associated with long bone skeletal abnormalities including osteochondritis and periostitis, hepatosplenomegaly and abnormal liver function studies, low birth weight, serous nasal discharge (snuffles), maculopapular rash, anemia, nephrotic syndrome, and CNS abnormalities. If untreated, these lesions may result in late congenital syphilis, which classically appears after 2 years and is manifest by frontal bossing, saddle nose, interstitial keratitis, notched and peg-shaped upper Hutchinson’s incisors, poorly developed mulberry molars, anterior bowing of the lower extremities, perioral and perinasal fissures, bilateral effusions of the knee (Clutton’s joints), and deafness.

Laboratory Findings

See Diagnosis below.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of congenital syphilis includes other congenitally acquired infections such as toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex, and hepatitis B.

Complications

Infants with untreated early syphilis may develop manifestations of late congenital syphilis, as previously described.

Diagnosis

Direct Microscopic Examination

Darkfield microscopy reveals T pallidum in the transudative fluid of a chancre in which the density of organisms approaches 10,000-100,000/mL. These spirochetes exhibit “corkscrew” motility and central flexion. Highly suspicious lesions should be examined on three successive days before excluding syphilis. Alternative diagnostic methods such as fluorescent antibody staining should be considered for the evaluation of oral lesions because saprophytic spirochetes in the oral cavity morphologically mimic T pallidum. Silver or specific immunofluorescent antibody stains may be useful in detecting pathogenic spirochetes in tissue biopsy specimens.

Serologic Tests

The majority of syphilis cases are diagnosed with serologic testing. These tests are categorized according to the type of antibody produced by the host: nonspecific and specific. Nonspecific, or nontreponemal, antibody tests use reaginic lipoidal antigens to demonstrate the presence of cross-reacting antibodies (immunoglobulin G [IgG] and IgM) elicited by T pallidum infection. Specific, or treponemal, antibody tests use T pallidum antigens for the detection of antibodies.

The nontreponemal antibody tests include the rapid plasma reagin and the VDRL flocculation assays. These screening tests may be reactive in the setting of other infectious and noninfectious conditions such as intravenous drug use, tuberculosis, vaccinations, pregnancy, infectious mononucleosis, HIV infection, rickettsial diseases, other spirochetal diseases, connective tissue diseases, and bacterial endocarditis.

False-negative nontreponemal tests can be seen early in the course of disease when antibody levels are low and later in the disease in the face of overwhelming antibody levels, for example, during secondary syphilis, necessitating dilution of the serum sample to overcome this “prozone” effect. Approximately 75%, 100%, and 75% of patients with untreated primary, secondary, and late syphilis, respectively, will have reactive nontreponemal tests. Positive test results are usually quantitated in order to monitor therapy.

The nontreponemal tests are not interchangeable (rapid plasma reagin titers usually higher at any given time), and the optimal approach for patient management should include the use of the same laboratory and test. Conversion to nonreactivity (seroreversion) or a sustained decline in titer of at least fourfold is expected in patients with early syphilis 2 years after effective therapy.

The more sensitive and specific treponemal antibody tests are used primarily for confirmation of results from nontreponemal antibody testing. The T pallidum hemagglutination and the microhemagglutination-T pallidum tests are dependent on the agglutination of antitreponemal antibodies from the patient’s serum with red blood cells that have surface-associated T pallidum. In the fluorescent treponemal antibody test, a killed strain of T pallidum serves as the antigen for the patient’s absorbed serum. Labeled antihuman immunoglobulin is then visualized with fluorescent microscopy. The fluorescent treponemal antibody test is more sensitive in detecting early syphilis than the other specific tests.

Seropositivity with the specific treponemal tests usually persists for the lifetime of the individual, a quality that does not allow monitoring response to therapy. However, seroreversion can be seen in promptly treated primary syphilis and in advanced HIV infection. In addition, treponeme-specific antibody tests are reactive in diseases caused by other pathogenic treponemes including yaws, pinta, and bejel, as well as Lyme disease, relapsing fever, and leptospirosis; false positives have also been reported in individuals with malaria and leprosy.

Molecular techniques, including polymerase chain reaction, are not routinely available, but may have use in resolving selected diagnostic conundrums involving early primary syphilis, congenital syphilis and neurosyphilis.

Neurosyphilis

The diagnosis of neurosyphilis is based on both clinical and laboratory findings. Although some experts evaluate the CSF of all patients with late latent syphilis, the U.S. PHS recommends a lumbar puncture when any of the following are present: clinical manifestations of neurologic involvement, evidence of nonneurologic late active syphilis, treatment failure, or late latent disease (including syphilis of unknown duration) in the HIV coinfected host. VDRL reactivity in the CSF is specific for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis, although caution should be exercised when interpreting a positive result from a traumatic lumbar puncture. In addition, the modest sensitivity of this test (~ 50%) does not rule out neurosyphilis when negative. Patients with systemic serologic evidence of syphilis and a CSF lymphocytic pleocytosis or an elevated CSF protein level should be treated for presumptive neurosyphilis.

Congenital Syphilis

U.S. PHS recommendations for the evaluation of an infant with suspected congenital syphilis include radiographs of the long bones, routine examination of the CSF including VDRL reactivity, nontreponemal serologies of the infant’s blood, and immunofluorescent antibody staining of the placenta or amniotic fluid/cord. If this initial evaluation is negative, specific antitreponemal IgM antibody testing is indicated. The definitive diagnosis of congenital syphilis requires identification of T pallidum in neonatal tissue.

Treatment

The drug of choice for all stages of syphilis is penicillin. Specific treatment recommendations are dictated by the stage of disease. Because of the organism’s slow replication, prolonged treponemicidal antimicrobial therapeutic levels are necessary. Although alternatives to penicillin are available, nonpenicillin-based therapy is not recommended for patients who are pregnant or have congenital syphilis, neurosyphilis, or HIV coinfection.

Patients with spirochetal diseases may develop an acute systemic reaction consisting of fever, chills, headache, and myalgias within the first day after effective therapy. This Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is usually seen during treatment of the earlier stages of syphilis, especially the secondary stage, and resolves spontaneously after 12-24 h. This reaction is probably caused by the lysis of spirochetes with subsequent release of antigen and toxic by-products. Symptomatic relief with anti-inflammatory agents may be helpful.

The recommendations given in Boxes 3, 4, and 5 for therapy and follow-up are based primarily on U.S. PHS recommendations.

Incubating Syphilis

Treatment of presumed incubating syphilis with the same regimen prescribed for early syphilis is recommended for all sexual contacts of patients with primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis, within the prior 90 days. Although the use of multiple-dose azithromycin and ceftriaxone appear promising in the treatment of early syphilis, single-dose therapy with either agent for incubating syphilis requires further evaluation.

Primary and Secondary Syphilis

The recommended therapy for adults with acquired primary and secondary syphilis is indicated in Box 3. Erythromycin therapy is less effective than penicillin, doxycycline, or tetracycline. Single-dose ceftriaxone or azithromycin therapy should not be used as alternative therapy. Follow-up in non-HIV infected patients should include nontreponemal titers at 3, 6, and 12 months after treatment.

Clinical manifestations of infection that recur or do not resolve or fourfold increases in nontreponemal titers suggest treatment failure or reinfection and should dictate further evaluation for neurosyphilis and HIV infection. Effective therapy usually results in a fourfold decrease in titer by 3-6 months after treatment, and a sustained fourfold or greater decline is considered an appropriate therapeutic response. Seroreversion fails to occur by 24 months after appropriate treatment in ~ 25% of patients with primary and secondary infection. Patients who are considered treatment failures and have no evidence of neurosyphilis should be treated with the benzathine penicillin G regimen recommended for late latent syphilis.

Early Latent Syphilis

Adults and children with early latent infection are treated in the same manner as those with primary and secondary syphilis.

Late Latent Syphilis or Syphilis of Unknown Duration

Nontreponemal serologic follow-up is recommended at 6, 12, and 24 months. Assessment for neurosyphilis and possible retreatment should be considered for patients in whom titers increase fourfold, in those in whom a fourfold decline is not seen in 1-2 years, or in whom clinical manifestations develop.

Late Syphilis

Patients with late benign syphilis or cardiovascular syphilis and no evidence of neurosyphilis are treated in the same manner as those with late latent disease. In addition to antitreponemal agents, therapy for cardiovascular syphilis consists of appropriate medical and surgical management of heart failure and aneurysm. Reversal of the complications of aortitis is unlikely, although progression of disease may be halted with antibiotics. The lesions of late benign syphilis are responsive to penicillin therapy.

Neurosyphilis

All patients with ocular and auditory involvement secondary to syphilis should be treated for presumed neurosyphilis. Follow-up examination of the CSF should be performed every 6 months. Effective therapy should result in a decrease of the CSF cell count by 6 months. CSF protein and VDRL titers do not respond as quickly as the cell count, but repeat therapy may be warranted if these two parameters are still abnormal 2 years after treatment. Treatment of the late stages of neurosyphilis is most effective at hindering further CNS damage but is unlikely to result in resolution of symptoms.

Congenital Syphilis

The appropriate therapy and follow-up of early congenital syphilis should prevent the development of late congenital syphilis (see Box 5). Benzathine penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg administered once intramuscularly, is recommended for neonates without clinical or laboratory evidence of syphilis when the mother’s syphilis serologies indicate treatment failure; neonates whose mothers have received prenatal erythromycin therapy for syphilis or have received therapy for syphilis in the month before parturition should also be treated with this regimen.

Treponemicidal CSF concentrations of penicillin may not be attained with the procaine penicillin regimen recommended for early congenital syphilis. Nontreponemal antibody test results should be negative by 6 months after therapy. Rising or persistent titers should prompt appropriate reevaluation and management including CSF examination and retreatment. Infants with abnormal CSF examinations should have follow-up lumbar punctures performed every 6 months with an expected serial decline in the cell count to normal levels by 2 years after therapy and a negative CSF-VDRL by 6 months. Retreatment is indicated if these parameters are not met.

Syphilis & Pregnancy

Therapy for all pregnant women known to be infected for <1 year should include benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million U given intramuscularly 1 week apart for a total of two doses. Other stages of disease are treated in the same manner outlined for nonpregnant adults, except there is no alternative to penicillin-based therapy. Nontreponemal antibody titers should be performed monthly with principles of retreatment guided by the disease stage. Treatment of all sexual partners is imperative.

Syphilis & HIV

HIV antibody testing is recommended for all patients with T pallidum infection because of the increased incidence of HIV coinfection in these patients. Transmission of HIV may be facilitated by genital ulcer disease. A weakened cellular immune system may explain why HIV-infected individuals develop atypical laboratory and clinical features of syphilis. Persistent chancres and initial presentations with secondary syphilis are reported more frequently in HIV-infected individuals. False-positive and false-negative serologies are more common in this patient population. Diminished serologic responses to therapy have also been observed in patients with early syphilis and HIV coinfection. The earlier appearance of neurosyphilis and other later stages of disease in HIV-infected patients has been ascribed to a decrease in the efficacy of standard therapy for early syphilis, although at least one recent randomized, double-blind study does not confirm this observation.

Confounding the evaluation and management of neurosyphilis in these patients are the elevated CSF protein and cell counts that can be seen in HIV infection alone. Despite these observations, standard serologic tests for syphilis are still recommended for diagnosis. However, some experts recommend more aggressive treatment of syphilis and more thorough evaluation of CNS infection in the HIV-infected host regardless of the stage of T pallidum infection. Penicillin-based therapies are recommended; close follow-up of response to therapy is essential.

Prevention & Control

No vaccine is currently available for the prevention of syphilis (Box 6). Primary prevention measures include behavior modification of patients engaged in high-risk practices such as sexual promiscuity and health programs designed to educate the public about sexually transmitted diseases, including the benefits of condom use. Secondary prevention measures include effective, affordable, prompt, and more accessible diagnostic and therapeutic interventions with appropriate follow-up for infected patients. Screening of all HIV-infected individuals and pregnant women is part of any effective public health prevention program. Reliable and thorough case reporting with partner notification and epidemiologic treatment is also essential.

BOX 1. Acquired Syphilis in Adults

Primary Syphilis

Secondary Syphilis

Latent1

Late

Neurosyphilis

More Common

- Genital ulcer (chancre)

- Inguinal lymphadenopathy

- Skin and mucous membranes: disseminated macular and papular rash; condylomata lata; mucous patch

- Constitutional, flu-like syndrome with generalized lymphadenopathy

- Asymptomatic by definition

- Benign (gummatous): skin, bone, and soft tissue granulomatous lesions

- Cardiovascular: aortic insufficiency, saccular aortic aneurysm, coronary ostial stenosis

- Asymptomatic

- Meningovascular (strokelike syndrome)

- General paresis: neuropsychiatric abnormalities of dementia

- Tabes dorsalis: ataxia, areflexia, lower extremity pain, incontinence, impaired proprioception

Less Common

- Musculoskeletal: osteitis, arthritis, periostitis, osteomyelitis

- Gastrointestinal: gastritis, hepatitis

- Nephropathy

- Neurosyphilis: aseptic meningitis

- Ocular: optic atrophy, blindness, ptosis

- Otic: deafness, tinnitus

Early, <1 year after infection; late, =1 year after infection.

BOX 2. Syphilis in Children

Early Congenital

Late Congenital

Acquired

More Common

- Osteochondritis and periostitis

- Snuffles/rhinitis

- Maculopapular rash, condylomata lata

- Anemia

- Low birth weight

- Hepatosplenomegaly

- Fever

- Dental abnormalities (Hutchinson’s incisors, mulberry molars)

- Poorly developed maxilla

- High palatal arch

- Saddle nose

- Frontal bossing

- Interstitial keratitis

See Box 64-1 (Acquired Syphilis in Adults

Less Common

- Lymphadenopathy

- Aseptic meningitis

- Meningovascular syphilis

- Pseudoparalysis

- Nephropathy

- Pneumonitis

- Ascites

- Mucous patch

- Saber shins

- Clutton’s joints

- Rhagades

- Eighth nerve deafness

- Flaring scapulae

- Mental retardation

- Hydrocephalus

BOX 3. Treatment of Acquired Syphilis in Adults

Primary, Secondary,

Early Latent

Late Latent, Latent of

Unknown Duration, Late

Neurosyphilis

First Choice

- Benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million U IM once

- Benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million U IM weekly for 3 weeks

- Aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 3-4 million Units IV every 4 h for 10-14 d (consider following with benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million U IM)

Second Choice

- Doxycycline, 100 mg PO twice daily for 14 d

OR

- Tetracycline, 500 mg PO four times daily for 14 d

OR

- Erythromycin, 500 mg PO four times daily for 14 d (less effective)

- Doxycycline, 100 mg PO twice daily for 28 d

OR

- Tetracycline, 500 mg PO four times daily for 28 d

- Procaine penicillin, 2.4 million Units IM once daily for 10-14 d PLUS probenecid, 500 mg PO four times daily for 10-14 d (consider following with benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million U IM)

Penicillin Allergic

- Doxycycline, tetracycline, or erythromycin as above

- Doxycycline or tetracycline as above

- No alternative to penicillin; desensitize and treat with penicillin

1) All patients who are pregnant or have HIV infection, congenital syphilis, or neurosyphilis should be treated with penicillin-based regimens.

2) Except neurosyphilis.

BOX 4. Treatment of Acquired Syphilis in Children

Primay, Secondary,

Early Latent

Late Latent, Latent of Unknown Duration,

Late

Neurosyphilis

First Choice

- Benzathine penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg IM, not to exceed the adult dose of 2.4 million U administered in one dose

- Benzathine penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg IM, not to exceed the adult dose of 2.4 million Units, weekly for a total of three doses

- Aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg IV every 4-6 h for 10-14 d (not to exceed recommended adult dose); consider following with benzathine penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg IM (not to exceed 2.4 million Units)

Second Choice

- Tetracycline, 500 mg PO four times daily for 14 d

OR

- Doxycycline, 100 mg PO twice daily for 14 d (in nonpregnant children = 8 years of age)

- Erythromycin, 500 mg PO four times daily for 14 d in children < 8 years of age

- Tetracycline, 500 mg PO four times daily for 4 weeks

OR

- Doxycycline, 100 mg PO twice daily for 4 weeks (in nonpregnant children = 8 years of age)

- Consider penicillin desensitization for children < 8 years of age

As above

Pencillin Allergic

See second choice

See second choice

Desensitize and treat with penicillin

1) All patients who are pregnant or have HIV infection, congenital syphilis, or neurosyphilis should be treated with penicillin-based regimens.

2) Except neurosyphilis.

BOX 5. Treatment of Congenital Syphilis is Children

Newborn

Older Infants & Children

First Choice

- Aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg IV every 12 h for the first week of life and every 8 h afterwards for a total of 10 days

- Aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg IV every 4-6 h for a total of 10 days

Second Choice: Penicillin Allergic

Procaine penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg IM in a single daily dose for 10 days; penicillin after desensitization

Pencillin after desensitization

1) All patients who are pregnant or have HIV infection, congenital syphilis, or neurosyphilis should be treated with penicillin-based regimens.

BOX 6. Control of Syphilis

Prophylactic Measures

- Prompt notification of public health department for contact followup and treatment

- Recommend safe sexual practices including condom use

- Screening of patients with HIV-infection, and those who are pregnant or have another STD

- Consider screening individuals who are sexually active and live in endemic areas

- Education and behavior modification of high-risk individuals

- Effective, expedient, accessible, and affordable diagnostic and therapeutic interventions for infected individuals

- Appropriate clinical and laboratory followup of treated individuals

Isolation Precautions

- Contact isolation for moist mucocutaneous lesions of congenital syphilis, primary, and secondary syphilis