Infection associated with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis is usually localized to the pulmonary mucosa. Most bacteria that infect the bronchial tree either reside as commensal organisms in the nasopharynx (e.g., H. influenzae) or act as opportunistic pathogens invading hosts with suppressed immune systems (e.g., P. aeruginosa). Mucosal infections are usually superficial, and most bacteria reside in the lumen, associating with mucus or other secretions. Some pathogenic bacteria adhere to the epithelial surface, particularly in areas of epithelial damage, while others infiltrate the mucosa.

In recent years, investigators have focused on determining if the presence of bacteria in the lower respiratory tract adversely affects lung function in patients with chronic bronchitis or acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Research also seeks to determine whether the frequency of exacerbations causes progression of the underlying airway disease in the long term, or vice versa. A “vicious cycle hypothesis” has been proposed as the mechanism by which bacteria may affect the lower respiratory tract. This hypothesis supposes that the primary initiating damage in chronic bronchitis results from cigarette smoke, childhood respiratory disease, or other factors, with bacterial colonization playing an important but secondary role.

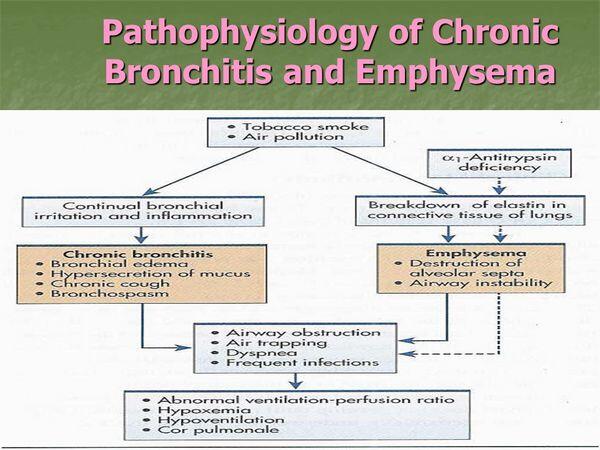

After initial damage to the lower respiratory tract, infection and/or bacterial colonization results in inflammation. The acute inflammatory response to airway infection stimulates mucus hypersecretion, airway-wall edema, and smooth muscle contraction. This inflammation is caused by the presence of cell-associated bacterial antigens (e.g., lipooligosaccharides from H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis, capsular material from S. pneumoniae) and the inflammatory response, which is provoked by the secretion of bacterial products (e.g., cilostatin), elastase from recruited polymorphonuclear leukocyte, and the production of cytokines. Chronic inflammation contributes to the damage done to the airway epithelium and to progression of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

FIGURE Schematic diagram of the vicious cycle hypothesis of the role of bacterial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Experts hypothesize that persistence of infection is more likely caused by the severity of the underlying disease and ensuing damage to the lung defenses rather than the virulence of the infecting pathogens. Thus, infections become more common with disease progression, further aggravating the underlying inflammatory process. The frequency of exacerbations that are bacterial in origin also depends on the predominant underlying pathology.

As such, patients with chronic bronchitis are more susceptible to bacterial bronchial infections than are those who have emphysema or asthma. Because bacteria have an affinity for growth in mucus, impairment of mucociliary clearance in the lungs and an increase in mucous production (as is the case in chronic bronchitis) allow bacteria that are inhaled or aspirated into the bronchial tree an opportunity to colonize the mucosa. In patients with mild chronic bronchitis, these infections can resolve spontaneously; however, as the underlying lung disease worsens, the ability to spontaneously resolve infection diminishes.

Immunological Hypothesis of Bacterial Re-Infection

Researchers have proposed a model for the recurrence of exacerbations and perpetuation of bacterial infection in patients with chronic bronchitis and acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This model assumes that the virulence of the infecting strain and the presence of preexisting protective antibodies are important factors. Absence — or low levels — of protective antibodies and/or virulent strains predispose an individual to development of an exacerbation. Infection with a low-virulence strain, on the other hand, would lead only to colonization, without inducing an exacerbation. Exacerbation (and possibly colonization) leads to development of antibodies to the infecting strain; these antibodies successfully clear the pathogen from the lower respiratory tract (with or without antibiotics).

Because a substantial proportion of the antibodies that the body mounts against infecting pathogens, particularly H. influenzae, are aimed at hypervariable regions of the outer membrane proteins (and therefore strain-specific), these antibodies do not protect the host from alternate strains that might be antigenically different. The strain-specific antibodies created by the host assist in protecting the lungs against the initial infecting strain, but new strains then replace the previous strain in a repetitive manner, leading to recurrence of exacerbation episodes.

This model suggests that important areas requiring further research include identifying pathogen virulence factors and identifying antigens on the surface of bacteria that are shared among several strains and can elicit a protective antibody response.

Role Of Host Defenses

The bronchi of normal lungs have a well-primed immune system that is ready to mount an inflammatory response to any insult, including infectious pathogens. Impairment of the host defenses in the bronchitic airways provides permissive conditions for invading bacteria to establish themselves in the bronchial tree. Cellular host defense mechanisms that can be impaired in patients with chronic bronchitis include the ability to phagocytose (engulf) bacteria by leukocytes (cells involved in host defense), the ability of the leukocytes to exert a bactericidal effect, and the excretion of macrophages and immunoglobulin A (IgA) in the sputum when infection is present.

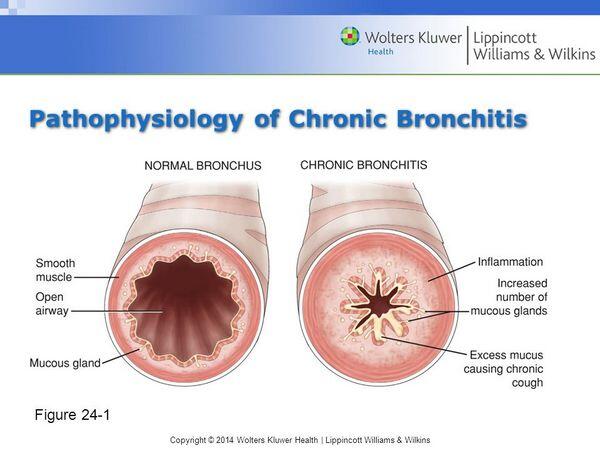

Repeated injury from high-dose inhalation of atmospheric pollutants or tobacco smoke leads to mucus hypersecretion, a change in the morphology of the airway (involving loss of ciliated cells, an increase in the number of nonciliated goblet cells, and mucosal gland hypertrophy), and the infiltration of chronic inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophages) into the mucosa.

Most experts now believe that an acute bacterial infection of the bronchi results in neutrophil infiltration into the bronchial lumen; inflammatory mediators then cause subsequent damage to the bronchial mucosa.

The by-products that the neutrophils release further impair host defenses. In the presence of chronic inflammation owing to an overwhelming number of by-products, these secretions can damage cilia and epithelial cells, stimulate mucus production, impair opsonization, and attract more neutrophils into the airway.

Epithelial cells and other inflammatory cell types (e.g., CD4+, CD8+, macrophages) are also probably essential in the initial inflammatory process leading to the breakdown of lung tissue. Many proinflammatory mediators can be measured in human secretions and serve as markers of infection. Also, patients with three or more exacerbations per year have higher baseline sputum cytokine IL-6 and IL-8 levels when stable, suggesting that frequent exacerbations are associated with increased inflammatory airway changes. Understanding the differences in the inflammatory cell types present in chronic airway diseases is a heated area of research and may be predictive of the various pathophysiological mechanisms associated with these diseases.

Stimulation and Evasion of the Host Defenses

Clinical Presentation Of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis

Clinical symptoms of a patient with acute exacerbation include increased severity of cough, increased sputum production, and purulent sputum-often associated with chest congestion and chest discomfort. Dyspnea and wheezing are present only when the patient has significant underlying pulmonary dysfunction. In addition, a patient may complain of malaise, fever, and chills. Patients may only have a few of these symptoms at presentation. Physical examination of a patient with an acute exacerbation may include the following findings: coarse rales, wheezes, decreased breath sounds, and tachycardia. The presence of these signs does not help in distinguishing which etiology is responsible for the specific acute exacerbation.

Complications Of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis

The complications of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis involve respiratory decompensation and side effects of infection. Patients with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis can decline into respiratory failure if the increase in the work of breathing cannot be maintained. Such cases require immediate ventilatory support. Repeated acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis can accelerate permanent structural damage in the lung. Further, infection in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis can progress to pneumonia and sepsis. Equally important complications of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis are the effects the disease has on comorbid conditions acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis can have a dramatic destabilizing impact on comorbid conditions, such as diabetes, congestive heart failure, and chronic renal failure, that may otherwise be well controlled.

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis include age and pulmonary diseases that increase inflammation and mucus production and impair airway clearance. Age is a risk factor because chronic cough and mucus production tend to increase with advancing age. In addition to the elderly, people at increased risk include those with other types of pulmonary disorders, such as asthma, and people with compromised immune systems.

Cigarette smoking is a factor in up to 90% of chronic bronchitis cases, and research suggests smokers already suffering from chronic bronchitis are also more vulnerable to aechronic bronchitis. Other known risk factors for chronic bronchitis and aechronic bronchitis are occupational exposure to dust, pollution (especially sulfur dioxide), and a history of childhood respiratory infection.

Comorbidities Of Patients with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis

Patients with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and underlying chronic bronchitis often have important comorbidities and may be taking medications that impact medical management and antibiotic selection.

They typically have a chronic history of smoking and therefore have subsequent development of obstructive lung disease. Comorbid conditions commonly include coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and chronic liver disease acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis may exacerbate other underlying comorbidities such as congestive heart failure and result in hospitalization. Treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis is particularly complicated because of the multiple (and often related) comorbidities.

For example, an acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis episode can decompensate patients with otherwise stable congestive heart failure or coronary artery disease and require them to be hospitalized. Complications and comorbidities associated with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis have a large impact on overall cost of therapy (the treatment costs associated with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis are largely due to hospitalization) and on the choice of therapy to minimize drug interactions. The presence of comorbid conditions can increase hospitalization (thereby increasing cost of treatment) and the risk of treatment failure.