Overview

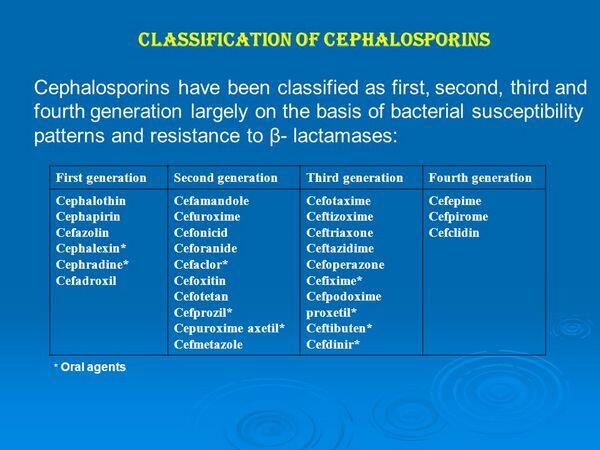

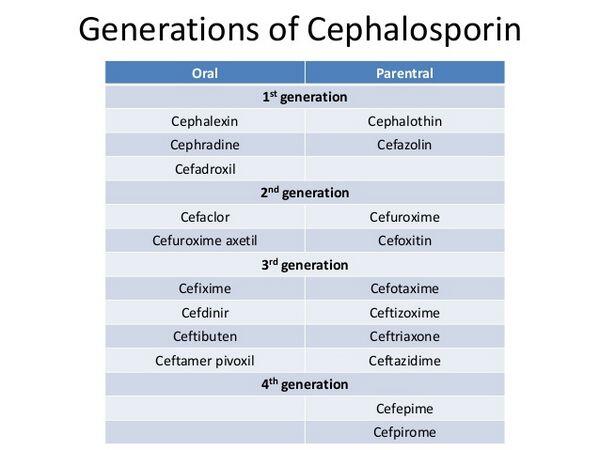

The cephalosporins contain a basic β-lactam structure fused to a six-membered ring. Drugs in this class differ widely in their spectrum of activity, susceptibility to β-lactamases produced by bacteria, and serum half-life. Cephalosporins are categorized into four generations, with each newer generation representing an improvement in the spectrum of bacterial coverage.

First-generation agents have the narrowest spectrum of activity among the cephalosporins. They are most active against staphylococci and streptococci organisms. Most first-generation cephalosporins are oral formulations. Second-generation agents have increased activity to cover more gram-negative bacilli, but are usually less active than the first-generation drugs against gram-positive bacteria. Second-generation oral cephalosporins are occasionally used to treat mild episodes of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis.

Third-generation cephalosporins are active against gram-negative organisms. However, their activity against gram-positive organisms is inferior to that of previous generations. These agents are commonly recommended in clinical guidelines for first-line treatment of patients hospitalized with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Compared with second-generation cephalosporins, the third-generation agents have greater stability against β-lactamases and have longer serum half-lives. As a result, they have more-convenient dosing regimens. The third-generation agents may also be used in combination with macrolides, extended-spectrum penicillins, or amino-glycosides to treat severe acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Fourth-generation agents have enhanced stability against β-lactamases and provide good coverage of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (particularly P. aeruginosa). However, they are generally reserved for severe, life-threatening infections such as sepsis.

As a class, the cephalosporins are generally well tolerated. Common adverse effects are usually minor; GI disturbances and thrombophlebitis are the most prominent with oral and intravenous (IV) agents, respectively. Disturbances of the GI tract are reported less often with cephalosporins than with the penicillins. Because of their relative safety and broad spectrum of activity, cephalosporins are commonly used to treat suspected as well as and proven bacterial infections.

Resistance against cephalosporins, as with other β-lactam antibiotics, results from pathogen changes in outer-membrane permeability, stability against β-lactamases, and modification of penicillin binding proteins. While β-lactamase production by H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis limits the use of certain penicillins such as amoxicillin, many cephalosporins are effective in treating infections caused by these β-lactamase-producing bacteria. Resistance to third-generation cephalosporins in gram-negative pathogens is a formidable problem in the hospital setting and is associated with adverse clinical outcomes and increased hospital costs.

Mechanism Of Action

As with the penicillins, the β-lactam ring of cephalosporins binds to penicillin binding proteins in bacteria and prevents bacterial cell-wall formation. By interrupting cell-wall formation, cephalosporins induce cell lysis and death.

(2 votes, average: 3.50 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 3.50 out of 5)