Potential Severity

An acute and severe illness associated with a high mortality.

Viral Encephalitis

Case 3

A 74-year-old white man with a history of chronic steroid use (10 mg prednisone daily) and stage I chronic lymphocytic leukemia presented at the emergency room with confusion and fever. Four days before admission, he complained of being increasingly tired. Two days before admission, he became increasingly lethargic, sleeping on floor. His wife had difficulty rousing him, and she noted that he was no longer interested in any activity.

The morning of admission, he displayed bizarre behavior (putting underwear on top of his pajama bottoms, for example). He also became unsteady, reguiring help from his wife to walk. His temperature at home was 38.9X (102°F). On arrival at the ER, he was mildly lethargic, but was talking and answering simple guestions.

The man was living in Florida with his wife. His wife reported that he spent considerable time outside and had been bitten by multiple mosguitoes.

Physical examination showed a temperature of 39.8X (103.6°F). No lesions in the mouth were noted, and the sclera lacked erythema. The neck showed some increased tone, but lacked Kernig’s or Brudzin-ski’s sign. A few rhonchi were heard in the lungs, but no murmurs or rubs in the heart, and the abdomen was unremarkable. No skin lesions were noted.

A neurologic exam revealed an ataxic gait, all extremities moving, some diffuse hyperreflexia, and generalized increased muscle tone.

By hospital day 2, the patient’s mental status had deteriorated. He only groaned and winced with painful stimuli.

Laboratory -workup included computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans of the head that were within normal limits. A lumbar puncture showed a white blood cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid of 100/mm3 (40% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 47% lymphocytes, 13% monocytes), with protein 106 mg/dL and glucose 68 mg/dL Serum immunoglobulin M for West Nile virus was markedly elevated.

Outbreaks of West Nile viral illness in North America, starting in the 1990s, have raised the public’s awareness and concern about viral encephalitis. The causative encephalitides fall into two major groups: those that are arthropod-borne, and those that are caused by viruses that spread person-to-person.

Table. Encephalitis Caused by Arboviruses

| Disease | Virus | Locations | Hosts | Clinical Remarks |

| Eastern equine encephalitis | Alphavirus | Eastern United States, Canada, Central and South America, Caribbean, Guyana | Birds, horses | Severe disease, high mortality |

| Western equine encephalitis | Alphavirus | United States,Canada, Central and South America, Guyana | Birds, small mammals, snakes, horses | Mild disease, primarily in children |

| Venezuelan equine encephalitis | Alphavirus | Northern South America, Central America, Florida,Texas | Horses, rodents, birds | Febrile illness, encephalitis uncommon |

| St. Louis encephalitis | Flavi virus | Western, central, and southern United States, Central and South America, Caribbean | Birds | Attacks people over 50 years of age |

| West Nile encephalitis | Flavi virus | Eastern United States (New York, Florida) | Birds | Usually mild disease, severe disease in elderly people |

| Japanese encephalitis | Flavi virus | Japan, Siberia, Korea, China, Southeast Asia, India | Birds, pigs, horses | Can cause severe encephalitis |

| California group encephalitis | Bunyavirus | United States,Canada | Small mammals | School-age children, permanent behavior changes |

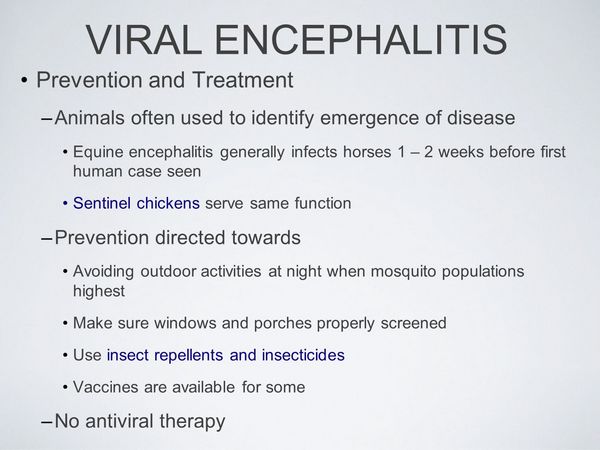

Mosquitoborne disease is caused by arboviruses that include the alphaviruses, flaviviruses, and the bunyaviruses. These infections occur in the summer months when mosquitoes are active. The responsible viruses often infect birds and horses in addition to humans. In the case of West Nile virus, crows are particularly susceptible, and the finding of a dead crow warrants increased surveillance. To document disease activity, public health officials frequently set out sentinel chickens in areas heavily infested with mosquitoes.

The various arboviruses tend to be associated with outbreaks in specific areas of the country, and these organisms have somewhat different host preferences. Prevention is best accomplished by avoiding mosquito bites. Long-sleeved shirts and long pants should be worn outdoors.

During times of increased viral encephalitis activity, people should avoid the outdoors in the early evening when mosquitoes prefer to feed. Insect repellants are another important protective measure.

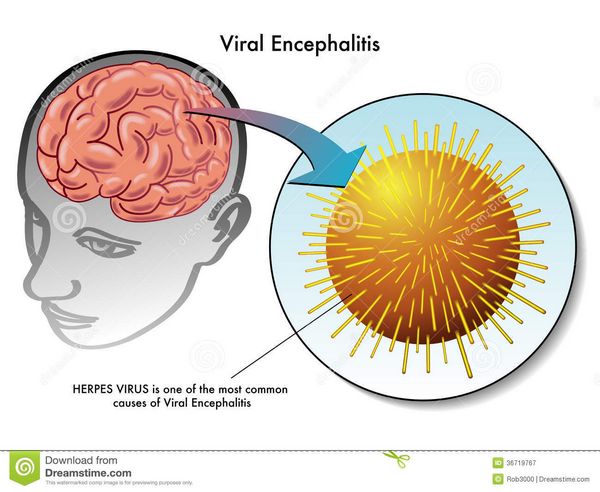

Encephalitis-causing viruses that spread from person-to-person include mumps, measles, Varicella virus, human herpesvirus 6, and the most common form of sporadic encephalitis, HSV-1. These forms of viral encephalitis can occur at any time during the year. Other, rarer causes of viral encephalitis include cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and enteroviruses. A particularly deadly form of encephalitis, rabies, is caused by the rabies virus, which is spread by animal bites, most commonly the bites of bats.

With the exception of rabies, these viruses all present with similar symptoms and signs, and cannot be differentiated clinically. The clinical manifestations of encephalitis differ from those of meningitis. The causative virus directly invades the cerebral cortex and produces abnormalities in upper cortical function. Patients may experience visual or auditory hallucinations.

Patients may perform peculiar higher motor functions such as unbuttoning and buttoning a shirt or placing underwear over pants. Patients with encephalitis frequently develop seizures that are either grand mal or focal in character. They may also develop motor or sensory deficits such as ataxia. These symptoms and signs are usually accompanied by severe headache.

As the disease progresses to cerebral edema, the patient may become comatose. Development of coma is associated with a poor prognosis. In herpes encephalitis, the typical vesicular her-petic lesions on the lip or face are not usually seen, because reactivated virus migrates up the Vth cranial nerve toward the central nervous system rather than toward the periphery.

Patients who contract rabies encephalitis often suffer the acute onset of hydrophobia. On attempting to drink water, they experience spasms of the pharynx. These spasms spread from the pharynx to the respiratory muscles, causing shallow, quick respirations. These abnormalities are thought to be the result of brain stem involvement and damage to the nucleus ambiguus in the upper medulla. Hyperactivity seizures, and coma usually follow. Pituitary dysfunction is often evident and can result in diabetes insipidus (causing loss of free water) or inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (causing hyponatremia).

Cardiac arrhythmias and auto-nomic dysfunction are also common. Patients usually die within 1 to 2 weeks after the onset of coma. Less commonly, patients present with ascending paralysis resembling the Guillain-Barre syndrome and subsequently develop coma.

Diagnostic studies usually include computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scan with contrast. The magnetic resonance imaging is more sensitive, detecting smaller lesions and early areas of edematous cerebral cortex. In herpes simplex encephalitis, involvement of the temporal lobes is the rule. In other forms of encephalitis, diffuse cerebral edema may be found in severe cases. However, these imaging studies are often normal. Electroencephalogram is particularly helpful in herpes simplex encephalitis, frequently demonstrating electrical spikes in the region of the infected temporal lobe.

Lumbar puncture usually reveals a cerebrospinal fluid white blood cell count below 500/mm, with a predominance of mononuclear cells. However, in early infection, polymorphonuclear leukocytes may be noted, and this finding warrants a follow-up lumbar puncture to document a shift to lymphocytes. The cerebrospinal fluid protein is usually normal or mildly elevated, and the cerebrospinal fluid glucose is usually normal, although low glucose may be seen in herpes. In HSV-1 encephalitis increased numbers of red blood cells may also be found in the cerebrospinal fluid.

With exception of rabies, a specific diagnosis is usually difficult to determine. Acute and convalescent serum should be sent for Immunoglobulin M and Immunoglobulin G titers to determine the viral causes of encephalitis. Samples of cerebrospinal fluid should be cultured for virus in addition to bacteria and fungi. Throat swabs for viral culture are also recommended. The yield for viral cultures is highest early in the illness.

A cerebrospinal fluid Polymerase chain reaction for HSV is both sensitive and specific; where available, it is the diagnostic test of choice. In the absence of this test, brain biopsy of the affected temporal lobe remains the diagnostic procedure of choice. Herpes immunofluorescence stain of cortical tissue has an 80% yield. Viral culture of the brain should also be obtained (takes lto 5 days to grow). In herpes encephalitis, histopathology classically reveals Cowdry type A intranuclear inclusions. Other stains including smear for acid-fast bacilli and stains for fungi should also be performed.

With the exception of HSV-1, most of the common causes of viral encephalitis have no specific associated treatment. One possible approach is to initiate acy-clovir therapy (10 mg/kg intravenously every 8 hours) while awaiting diagnostic tests, recognizing that a delay in therapy of herpes encephalitis worsens the prognosis.

About Viral Encephalitis

- Three major categories:

- Mosquito-borne (arboviruses)

- Animal-to-human (rabies virus)

- Human-to-human [herpes simplex 1 (HSV-1), mumps, measles, Varicella, human herpesvirus 6; less commonly, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomeg alovirus,and enteroviruses]

- Symptoms of cortical dysfunction are evident:

- Hallucinations, repetitive higher motor activity such as dressing and undressing

- Seizures

- Severe headache

- Ataxia

- Rabies causes distinct symptoms:

- Hydrophobia

- Rapid, short respirations

- Hyperactivity and autonomic dysfunction

- (Less commonly) ascending paralysis Diagnosis is often presumptive, requiring acute and convalescent serum analysis.

- Cerebrospinal fluid (cerebrospinal fluid) shows a white blood cell count below 500/mm3, mild increase in protein, possibly red blood cells (in cases of HSV-1)

- Polymerase chain reaction of cerebrospinal fluid diagnoses HSV, culture is seldom positive.

- A computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scan may show temporal lobe abnormalities in HSV-1 infection.

- An electroencephalogram may show localized temporal lobe abnormalities in HSV infection.

- Brain biopsy is likely necessary in the presence of temporal lobe abnormalities and no improvement on acyclovir.

Treat with acyclovir for possible HSV-1 infection.

Prevent disease

Avoid mosquito bites during epidemics. Wash wounds inflicted by rabies-infected animals; give immune globulin and rabies vaccine.

If temporal lobe abnormalities are found and if the patient fails to improve on acyclovir, a brain biopsy should be strongly considered. In other forms of encephalitis in which no focal cortical abnormalities are noted, the usefulness of brain biopsy remains to be determined. If HSV is confirmed by Polymerase chain reaction, culture, or biopsy, intravenous acyclovir should be continued for 14 to 21 days.

The prognosis of viral encephalitis varies depending on the agent. A mortality of 50% to 60% is associated with HSV-1, and the frequency of neurologic sequelae is high. Early treatment reduces mortality. The mortality for rabies is nearly 100%, justifying vaccination of anyone who has potentially been exposed to the rabies virus. The prognoses for arboviruses depend on the patient’s age, the extent of cortical involvement, and the specific agent. Eastern equine encephalitis tends to be the most virulent, having a 70% mortality; Western equine encephalitis is usually mild and often subclinical, infecting primarily young children. West Nile virus infection is also often subclinical or causes just mild disease; however, in elderly individuals, this virus can cause severe, life-threatening disease that can be accompanied by flaccid paralysis. Venezuelan equine encephalitis is also usually mild, and Japanese encephalitis varies in severity.

Management of rabies exposure is complex, and specific guidelines have been published by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Bite wounds should be washed with a 20% soap solution and irrigated with a virucidal agent such as povidone iodine solution. Rabies immune globulin (20 IU/kg) should be injected around the wound and given intramuscularly. Several safe and effective anti-rabies vaccines are available. The vaccine should be given on days 0, 3, 7, 14, and 28.