ASPERGILLUS INFECTION

Essentials of Diagnosis

- Filamentous fungus with septate hyphae 3-6 um in diameter.

- Branching of hyphal elements typically at 45° angle.

- Specific IgG antibodies generally of no use diagnostically since most patients are immunosuppressed and will not generate antibody response.

- Pulmonary lesions, localized or cavitary in susceptible host.

General Considerations

Epidemiology

Aspergillus spp. are found worldwide and grow in a variety of conditions. They commonly grow in soil and moist locations and are among the most common molds encountered on spoiled food and decaying vegetation, in compost piles, and in stored hay and grain. Aspergillus spp. often grow in houseplant soil, and such soil may be a source of Aspergillus conidia or spores in the home, office, or hospital setting. The airborne conidia are extremely heat resistant and can withstand extreme environmental conditions.

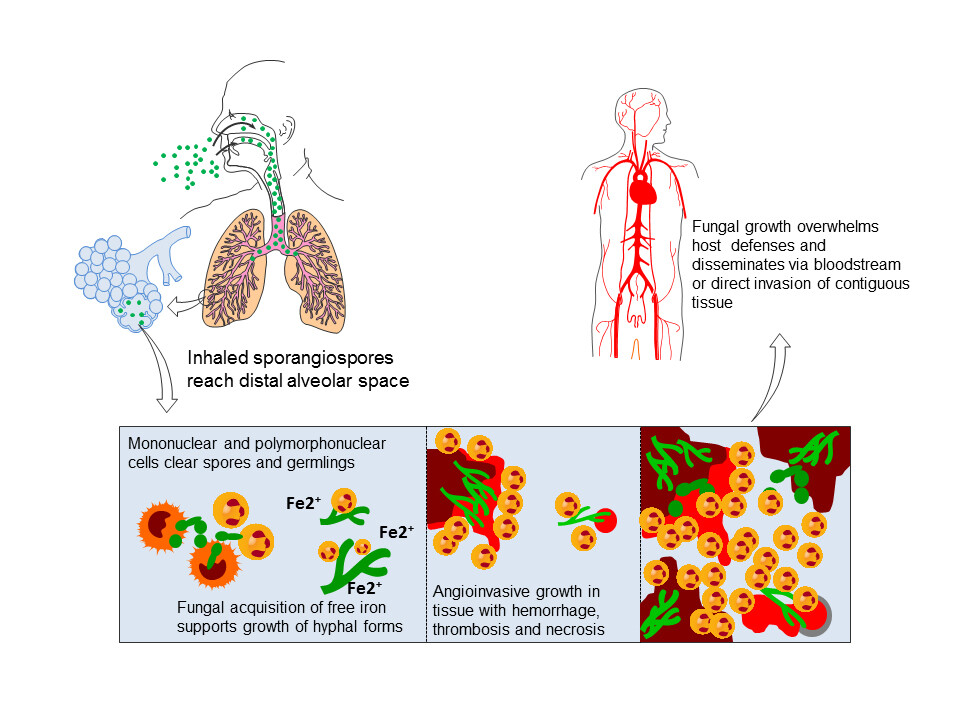

Most human disease with Aspergillus spp. is acquired via inhalation of conidia. Conidia are 2.5-3 um in size and can easily reach the alveoli with inhalation. Other routes of transmission are by direct inoculation of skin, inhalation into the nose and sinuses, or injection into the bloodstream among drug abusers. Person-to-person transmission does not occur.

Nosocomial acquisition is an important problem among severely immunosuppressed, hospitalized patients. Hospital air and air ducts are known sources of A conidia. Unfiltered air is more likely to contain spores. Construction, building remodeling, and other forms of environmental disruption have been associated with nosocomial outbreaks of aspergillosis. Potted plants are frequently excluded from patient care areas where high-risk patients may be present.

The most critical determinant for inhalation of A conidia progressing to invasive disease is the status of the host defenses. The pulmonary macrophage is the first line of defense against inhaled conidia. Macrophage function may be rendered ineffective by high-dose corticosteroid therapy or other immunomodulating chemotherapy. The tissue neutrophil is also pivotal. Altered phagocytosis or cellular killing by the neutrophil may lead to invasive disease. Neutropenia caused by leukemia, chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, or aplastic anemia is a well-known risk factor for invasive aspergillosis. Patients with late stages of HIV infection also are prone to invasive disease. Increased risk is also associated in children with chronic granulomatous disease and in patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.

Microbiology

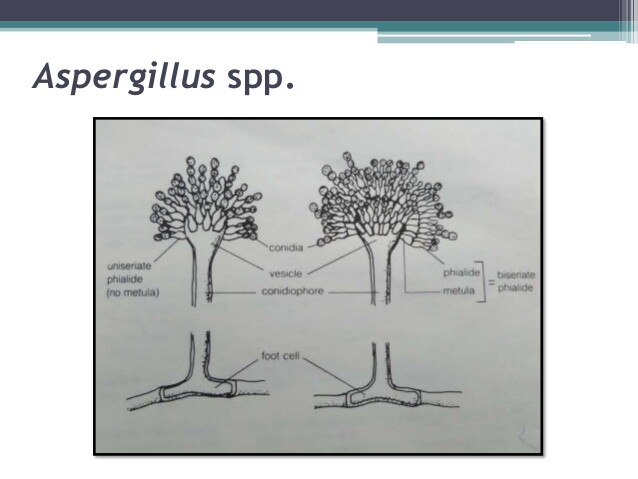

Aspergillus spp. are rapidly growing filamentous fungi or molds that are ubiquitous in the environment and found worldwide. The septate hyphae are characteristically 3-6 um in diameter and usually branch at 45° angles. Growth usually occurs in the laboratory within 2-3 days. Of the > 500 species of Aspergillus, only a few cause human infection. A fumigatus is the most common human pathogen. Others, such as A niger, A flavus, and A terreus, can also cause human infection but are encountered less frequently. Isolated cases have been caused by a number of other Aspergillus spp. The species of Aspergillus are differentiated by the structure of the asexual conidiaphore or spore-forming structure on growth in the laboratory.

Pathogenesis

Aspergillus spp. may invade tissue in patients with altered host defenses or may colonize ectatic segments or cavities in the lung. Following inhalation of conidia, in the absence of appropriate host response, hyphal elements invade bronchial tissue with a particular propensity for angioinvasion. Angioinvasion may lead to disseminated invasive aspergillosis involving multiple organs in profoundly immunosuppressed patients. Furthermore, angioinvasion causes hemorrhagic infarction and necrosis of involved tissue. This may result in hemoptysis when there is pulmonary involvement or stroke when the brain is infected. The enlarging site of Aspergillus infection with central necrosis has a tendency to cavitate, yielding characteristic findings on imaging studies.

Colonization of preexisting cavitary lesions may lead to the formation of a fungus ball or aspergilloma composed of exuberant filamentous growth of Aspergillus spp. The cavity of an aspergilloma is lined by vascular granulation tissue, while the cavity itself contains hyphal elements, inflammatory cells, amorphous debris, and mucus. Superficial invasion of the cavity wall may occur, but dissemination is rare unless the patient also has other risk factors for invasive disease. Erosion into adjacent pulmonary vessels may occur and result in hemoptysis, which on occasion may be massive and result in death.

CLINICAL SYNDROMES

Most individuals who are exposed to Aspergillus spores are asymptomatic. In fact, inhalation of spores is probably a common event; however, in an at-risk patient, the spectrum of disease caused by Aspergillus spp. can range from hypersensitivity phenomenon to colonization to overwhelming and rapidly progressing disseminated life-threatening disease (see Box 1).

Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis

DISSEMINATED ASPERGILLOSIS

Disseminated aspergillosis is a life-threatening, usually fatal form of aspergillosis that occurs in immunosuppressed patients. By definition, two or more noncontiguous sites are involved. Most patients with disseminated disease have invasive pulmonary aspergillosis as the primary site of infection. Common sites of dissemination include central nervous system, skin, liver, kidney, skin, and gastrointestinal tract.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with disseminated aspergillosis are usually critically ill. There are no typical signs or symptoms of disseminated disease, and findings will depend on the sites of dissemination. Pulmonary symptoms may predominate if invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is present. Altered mental status, particularly when associated with focal neurological findings, is suggestive of central nervous system involvement. Renal and hepatic involvement may be completely asymptomatic. Invasion of the renal artery or vein may cause thrombosis or infarction. Cutaneous involvement may appear as small erythematous papules and microabscesses or as large black necrotic lesions.

Laboratory Findings

Despite hematogenous route of dissemination, blood cultures are rarely positive. Urine cultures may be positive for Aspergillus cells when the kidney is involved. Elevated hepatic enzymes or serum creatinine may reflect involvement of the liver or kidney.

Imaging

CT imaging or MRI of the brain may show a single lesion or multiple mass lesions. CT imaging of the abdomen may reveal nodules in affected organs. Cavitation is common.

Complications

The complications of disseminated disease are related to the sites of specific organ involvement. For example, brain abscesses may be associated with mental status changes or seizure, splenic abscesses may be suspected if there is left upper quadrant pain, or complete heart block may be present if there is cardiac involvement. Multiorgan dysfunction often develops.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be suspected in severely immunosuppressed hosts with multiorgan dysfunction. Often the diagnosis is presumptive, but the diagnosis may be confirmed by biopsy of suspected sites of dissemination. Unfortunately, in = 30% of cases of disseminated aspergillosis, the diagnosis is established at autopsy.

Treatment, Prevention, & Control

The treatment, prevention, and control of disseminated aspergillosis are identical to that of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

ALLERGIC BRONCHOPULMONARY ASPERGILLOSIS

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is an eosinophilic pneumonia or hypersensitivity reaction, which generally occurs in adults with a prior history of allergic asthma. It is also seen in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

The presenting symptoms are usually worsening asthma that is difficult to control and cough productive of thick brownish plugs of sputum. Low-grade fever may be present, and some patients may exhibit nonspecific constitutional symptoms such as malaise and fatigue.

Laboratory Findings

Peripheral eosinophilia is a hallmark of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and is usually > 1000 cells/mL. Other findings include elevated serum IgE levels, serum precipitans to Aspergillus fumigatus, and immediate wheal and flare response to Aspergillus skin testing. Culture of the sputum reveals large numbers of A fumigatus colonies. Antibodies in both the IgG and the IgE class that are specific for A fumigatus are elevated.

Imaging

Pulmonary infiltrates are commonly seen on chest x-ray and usually involve the upper lobes. Transient recurrent infiltrates may also be seen. CT imaging of the chest is helpful in identifying the presence of central bronchiectasis that may develop in untreated patients.

Differential Diagnosis

Other common causes of eosinophilic pneumonia include parasitic infestation and drug-induced lung disease. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis must also be distinguished from a number of idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonias including Loffler’s syndrome, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, Churg-Strauss syndrome, and hypereosinophilic syndrome.

Complications

Undiagnosed disease may develop into a chronic state typically with involvement in the upper lobes of the lungs. Bronchiectasis, usually involving the central airways, and fibrosis may develop. Hemoptysis with chronic disease is common.

Diagnosis

The main criteria for establishing the diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis are a history of bronchial asthma, presence of peripheral eosinophilia, immediate reaction to Aspergillus fumigatus antigen, pulmonary infiltrates on chest x-ray, serum precipitants to A fumigatus, elevated serum IgE level, and central bronchiectasis on CT imaging of the chest (see Table 1). Supportive diagnostic criteria include a history of brownish sputum production, sputum culture positive for A fumigatus, and elevated antibodies specific for A fumigatus of the IgG and IgE class. Microscopic examination of sputum may reveal brown, lancet-shaped crystals originating from the Charcot-Leyden crystal proteins found in the cytoplasm of eosinophils.

Treatment

Treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis requires corticosteroids therapy (Box 2). After initial control of symptoms, the corticosteroid therapy should be slowly tapered. Itraconazole has been used in some patients who have difficulty controlling allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, but its role is still under investigation. Inhaled corticosteroid therapy does not appear to be effective.

Prognosis

Recurrent disease is common, and prolonged maintenance of low-dose corticosteroid therapy is required in many patients.

OTHER FORMS OF ASPERGILLUS INFECTION

A variety of less commonly encountered infections may occur in both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. Endophthalmitis may occur following surgery or trauma to the globe or as a rare manifestation of invasive disseminated aspergillosis. Osteomyelitis may occur in children with chronic granulomatous disease and in adults who are immunosuppressed. Disk space infection with adjacent vertebral osteomyelitis has been described in both normal hosts and in injection drug abusers. Endocarditis may occur in patients with a prosthetic valve or native valve endocarditis may occur in injection drug abusers. Otomycosis can occur in the setting of chronic external otitis.

In immunosuppressed patients, an invasive form of the disease with extensive bony destruction can occur. Aspergillus tracheobronchitis is seen most commonly in lung transplant recipients but can also occur in other immunosuppressed patients. Invasive aspergillosis may begin in the skin and disseminate to other sites. For example, focal infection may develop at intravenous catheter sites in neutropenic patients and cause progressive local infection before there is evidence of systemic dissemination.

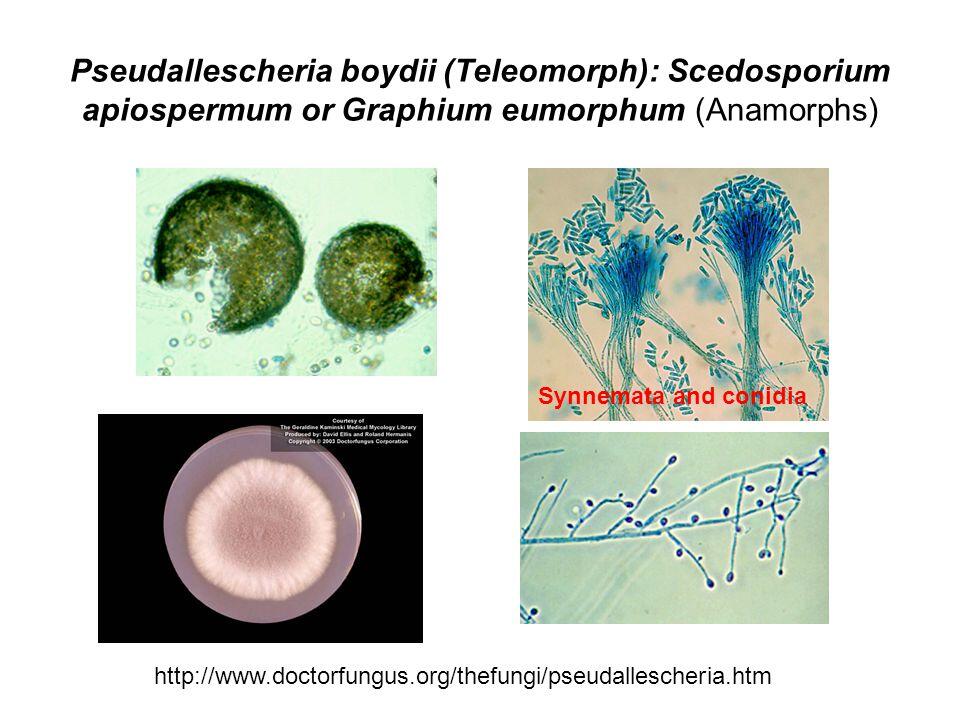

Pseudallescheria Boydii Infection

MUCORMYCOSIS

Essentials of Diagnosis

- Filamentous fungus with hyphae of uneven, often very large diameter (5-50 um).

- No or rare septation of the hyphal elements, which branch at irregular angles.

- No availability of antibody or antigen testing to assist diagnosis.

- Often abundant in biopsy or clinical specimens on fungal stain but no growth from fungal cultures.

General Considerations

Mucormycosis refers to a spectrum of infections caused by fungi of the phylogenetic order Mucorales. These infections are generally quite rare and usually occur in patients with either severe immunodeficiency, uncontrolled diabetes, or trauma.

Epidemiology

The agents of mucormycosis are ubiquitous in nature and commonly recovered from decaying organic manner. Rhizopus spp. are especially common on moldy bread. Nevertheless, in contrast to Aspergillus species, the agents of mucormycosis are rarely recovered in the hospital setting.

Microbiology

Although there are numerous fungi capable of causing mucormycosis, the four most common genera in order of frequency are Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, Absidia, and Cunninghamella. These fungi are relatively rapid growing and will grow on most media in the mycology laboratory in 2-5 days. They grow only as mold, and the hyphae tend to be uneven in diameter and often quite large, ranging in size from 5 to 50 um. Branching occurs at irregular angles, in contrast to the 45° angles of branching by Aspergillus spp. Septation of the hyphae is usually absent. Environmental specimens often grow rapidly and abundantly, but it is common for no growth to occur from specimens obtained from infected tissue in patients with mucormycosis. The reason for this is unknown.

Pathogenesis

Although inhalation of spores produced by these fungi is probably a daily occurrence, infection rarely occurs, even among susceptible hosts. Therefore the presumed portal of entry is respiratory with deposition of spores on the nasal mucosa for rhinocerebral mucormycosis and in the alveoli for pulmonary mucormycosis. Gastrointestinal mucormycosis is thought to occur following ingestion of spores, and cutaneous mucormycosis is a consequence of direct inoculation of traumatized skin. Alteration of macrophage and neutrophil function secondary to diabetic ketoacidosis and corticosteroids allows the initial sporulation and filamentous growth. Once tissue invasion is achieved in a susceptible host, the disease can progress at an alarming rate or be quite indolent. Angioinvasion by hyphal elements is common and results in ischemic and hemorrhagic necrosis.

Mucormycosis: Clinical Syndromes

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

Key diagnostic criteria

- Bronchial asthma

- Peripheral eosinophilia

- Immediate wheal and flare response to Aspergillus fumigatus antigen

- Pulmonary infiltrates on chest x-ray

- Serum precipitans to A fumigatus

- Elevated serum IgE level

- Central bronchiectasis

Specific supportive criteria

- Brownish sputum production

- Sputum cultures positive for A fumigatus

- Elevated specific IgG and IgE

Table 2. Clinical aspects of Aspergillus sinusitis.

Noninvasive

Invasive

Host

Immunocompetent

Immunosuppressed and usually profoundly

Tempo of Infection

Chronic and indolent

Acute and progressive

Pathologic features

Fungus ball and chronic local infeciton

Bony destruction with invasion of adjacent structures

Clinical features

Pain, congestion, and discharge

Pain, congestion, and discharge

Fever

Rare

Usually present

Treatment

Excision and drainage

Wide surgical debridement and amphotericin B, 1.0 mg/kg/d

BOX 1. Aspergillus Infection

Children

Adults

More Common

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

- Aspergilloma

- Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

- Disseminated aspergillosis

- Farmer’s lung

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

- Aspergilloma

- Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

- Disseminated aspergillosis

- Aspergillus sinusitis

Less Common

- Osteomyelitis

- Endocarditis

- Endophthalmitis

- Endophthalmitis

- Osteomyelitis

- Disk space infection

- Endocarditis

- Otomycosis

- Aspergillus tracheo-bronchitis

BOX 2. Treatment of Aspergillus Infection in Children and Adults

Treatment

Option

Farmer’s Lung

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

Aspergilloma

Invasive Pulmonary

Aspergillosis and

Disseminated

Asperillosis

Aspergillus

Sinusitis

Corticosteroids

Prolonged subacute or chronic symptoms may require prednisone therapy at 1 mg/kg for 1-2 wks followed by a tapering regimen

Prednisone, 0.5 mg/kg/d prolonged with slow taper

No

Stop or reduce if possible

No

Amphotericin B

No

No

No

1.0-1.5 mg/kg/d IV (2-3 g total target dose) in adults; 30-35 mg/kg total dose in children

1-1.5 mg/kg, if needed (2-3 g total target dose) in adults; 30-35 mg/kg total dose in children

Intraconazole

No

Investigational

No

400 mg PO once daily as second-line option for indolent case or after IV amphotericin B induction therapy; itraconazole dose for children, 5-6 mg/kg/d

No

Surgery

No

No

In selected cases

An option for localized disease

Surgical debridement; surgical excision and drainage may be adequate

BOX 3. Control and Prevention of Nosocomial Invasive Aspergillus spp. in Immunosuppressed Patients

Strategy

Goal or Limitations

Reduction of environmental exposure

- Remove potted plants from patient care areas

- Avoid dried spices (eg, pepper) and cereals

- Seal off hospital remodeling projects

- HEPA filtration and laminar air flow patient room and care areas

- Wear high filtration masks during transportation in hospital

- Eliminate source of spores

- Reduce air contamination

- Remove spores from air in key domiciliary areas; reduce exposure risk in non-domiciliary areas

Prophylactic antifungal therapy

- Amphotericin B, 1 mg/kg/d IV

- Amphotericin B, 0.1-0.15 mg/kg/d

- Lipid preparations of amphotericin B

- Oral itraconazole, 200-400 mg/d; for children 3-6 mg/kg/d

- Intranasal or aerosolized amphotericin B

- Too toxic to be used prophylactically

- Usually can be tolerated but dose may be too low to be effective

- No clinical data; prohibitive cost

- Limited clinical data; unpredictable absorption

- Promising approach; more data needed

BOX 4. Treatment of Pseudallescheriosis

First Choice

Miconazole, 800 g IV every 8°; for children: 20-40 mg/k in 3 divided doses

Second Choice

Itraconazole, 400 mg PO once daily; for children; 5-6 mg/kg/d

Role of Surgery

In selected cases

Comments

Amphotericin B resistant

BOX 5. Treatment of Mucormycosis in Children and Adults

First Choice

Amphotericin B, 1-1.5 mg/kg/d IV

Second Choice

Lipid formulation of amphotericin B

Role of Surgery

Debridement required for rhinocerebral form

Comments

Azoles appear to be ineffective