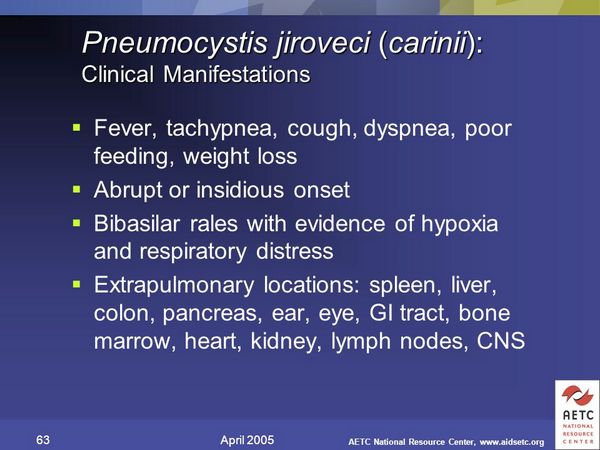

Extrapulmonary P carinii infections occur in < 3% of patients and must be diagnosed with histopathologic samples. Primary prophylaxis for PCP with pentamidine may confer a higher risk for extrapulmonary infection.

Symptoms of extrapulmonary involvement are nonspecific, usually consisting of fevers, chills, and sweats. Although any area of the body may be involved, splenomegaly with cysts and thyroiditis are most common.

Diagnosis

The practice of diagnosing PCP morphologically by traditional staining methods (silver methenamine and toluidine blue) of induced sputum samples in HIV-infected individuals has fallen out of favor. Although relatively simple and inexpensive, staining of sputum samples induced by hypertonic saline inhalation is clearly dependent on operator and laboratory experience, and sensitivity varies tremendously between centers. These classic staining techniques yield a diagnosis in only 30-90% of patients suspected of being infected with PCP. Subsequently, a large number of patients may continue to be treated with potentially toxic drug regimens without a definitive diagnosis. The practice of indirect immunofluorescent stain with monoclonal antibodies has increased the sensitivity of induced sputum samples to ~ 70% or to > 90% in some reports.

Bronchoscopy with BAL with or without transbronchial biopsy has become the gold standard in the diagnosis of PCP. Several studies have demonstrated a sensitivity of > 90% for both BAL and transbronchial biopsy. The combination of BAL and transbronchial biopsy leads to a sensitivity of ~ 100%. The complications of transbronchial biopsy, including bleeding and pneumothorax, have led most clinicians to use BAL as the initial diagnostic method during bronchoscopy if diagnosis is not obtained by induced sputum.

PCR technology on induced sputum samples has improved sensitivity to ~ 100% but appears to result in diminished specificity. PCR may become a reasonable diagnostic tool as PCR technique improves, resulting in less contamination and fewer false-positive results.

Chemoprophylaxis for PCP with aerosolized pentamidine has led to a considerable reduction in the rate of recovery of PCP in sputum and bronchoscopy samples. Performing BAL bilaterally or on multiple lobes seems to maintain sensitivity at > 90%.

Treatment

The primary treatment of moderate to severe pulmonary or extrapulmonary infection caused by P carinii remains the combination of trimethoprim (TMP) and sulfamethoxazole (SMX), either orally or intravenously (IV).

Several medications (atovaquone, trimetrexate, and pentamidine) and combination regimens (dapsone + TMP and clindamycin + primaquine) probably afford nearly equal efficacy to TMP-SMX in mild to moderate PCP and may be better tolerated in specific populations of patients (Boxes 2 and 3).

TMP-SMX

TMP-SMX was the first regimen approved for use in the treatment of PCP, and this regimen is still considered the best initial treatment choice for PCP infection. If tolerated, this combination should be regarded as the initial treatment choice for all PCP infections.

In moderate to severe pulmonary infection with P carinii, TMP-SMX has been shown to significantly improve survival when compared with IV pentamidine (86% vs 61%) in randomized trials. Several drug regimens subsequently discussed appear to have similar efficacy compared with TMP-SMX in mild to moderate PCP and may be better tolerated. However, the fact that TMP-SMX also has excellent antimicrobial activity against organisms causing community-acquired bacterial pneumonia and Toxoplasma infections should be considered when choosing an agent for treating P carinii infections.

Treatment with TMP-SMX is often limited by adverse effects, which occur in the majority of patients to some degree (65-100%). A morbilliform rash is the most commonly observed adverse reaction among patients treated with TMP-SMX; the rash occurs ~ 20-45% of the time and limits treatment in = 20% of patients. Antihistamines may be used to reduce the severity of the rash. Additional side effects of TMP-SMX include fever, nausea and vomiting, neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated serum aminotransferase levels.

Pentamidine isethionate

IV pentamidine isethionate is a suitable alternative treatment for PCP if TMP-SMX is not tolerated. Pentamidine appears to be comparable to TMP-SMX in effectiveness in mild to moderate disease. However, a randomized trial comparing IV pentamidine isethionate with TMP-SMX in moderate to severe disease resulted in a significant mortality advantage for patients treated with TMP-SMX (86% vs 61%).

Aerosolized pentamidine isethionate has been used in the treatment of mild to moderate PCP. Unfortunately, although it results in fewer systemic adverse effects, the aerosolized form of pentamidine isethionate has resulted in lower response rates and a higher frequency of relapse. The use of aerosolized pentamidine isethionate is expensive and requires compressed air to be delivered effectively.

The most common adverse effects associated with the use of pentamidine isethionate include nephrotoxicity, hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, hypoglycemia, and hypotension. The hypotension seems to be related to the rate at which the drug is administered and usually responds to IV fluids. Hyperglycemia and insulin dependence can also occur. Acute pancreatitis has also been reported.

Trimetrexate

Trimetrexate is relatively new in the spectrum of drugs used to treat PCP. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved trimetrexate for use in moderate to severe PCP in late 1993. Trimetrexate is related structurally to methotrexate and is thought to possess a similar mechanism of action. Trimetrexate presumably inhibits dihydrofolate reductase, which diminishes the production of nucleic acid precursors, resulting in cell death. Thus, a reduced form of folic acid, folinic acid (leucovorin), must be administered with trimetrexate to reduce toxicity to host cells.

Trimetrexate has been compared with TMP-SMX in a randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial in a group of patients with moderate to severe PCP. Trimetrexate was relatively well tolerated; only 8% of patients terminated treatment before 21 days because of adverse effects. By comparison, 28% of patients who received TMP-SMX had discontinued therapy by 21 days (P < 0.001). However, by 21 days after initiation of treatment, a significantly larger number of patients receiving trimetrexate had been considered treatment failures as measured either by lack of efficacy or death (38%) vs those receiving TMP-SMX (20%). Thus, trimetrexate should be considered a relatively safe treatment option in patients with moderate to severe PCP who do not respond to or are intolerant of TMP-SMX or in patients in whom TMP-SMX is contraindicated.

Trimetrexate, as mentioned, has been well tolerated, with = 10% of patients discontinuing therapy at 21 days. The principal dose-limiting side effect has been myelosuppression, especially neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, occurring in 10-15% of patients. Elevated serum aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and creatinine levels have been reported as well. Rash and anemia may also occur in patients receiving trimetrexate.

Atovaquone

Atovaquone is a hydroxynapthoquinone drug that has proven to be an effective alternative in the treatment of mild to moderate PCP. Several multicenter prospective trials have shown atovaquone to be much better tolerated than either TMP-SMX or pentamidine isethionate. Although atovaquone is somewhat more likely to result in treatment failure, the favorable side effect profile of atovaquone compared with TMP-SMX and pentamidine isethionate has led to equivalent overall clinical success rates of ~ 60-80%. Mortality rates appear similar between atovaquone and pentamidine isethionate = 8 weeks after completion of treatment. However, mortality appeared significantly higher with atovaquone (7%) as compared with TMP-SMX (0.6%) in a randomized multicenter trial (P = 0.003).

The adverse effects of atovaquone that lead to termination of treatment seem to occur in < 10% of patients over a typical 21-day course of treatment. Gastrointestinal complications arise most frequently and include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hepatitis, and constipation. In addition, an erythematous rash has occurred in = 25% of patients who take atovaquone. Fever and cough are also common side effects.

Clindamycin and Primaquine

The use of the combination of clindamycin and primaquine has been proven quite effective in the treatment of mild to moderate PCP.

Several prospective trials have proven that clindamycin and primaquine are = 90% effective in treating mild to moderate PCP. No significant difference has been demonstrated between clindamycin and primaquine when compared with either TMP-SMX or dapsone-TMP, in mild to moderate disease.

Adverse effects have occurred in up to one-third of patients receiving clindamycin and primaquine, and they may be related to the dose of primaquine used. When primaquine has been dosed at 30 mg/d instead of the more frequently used dose of 15 mg/d, the incidence of dose-limiting side effects has nearly doubled. The most significant dose-limiting adverse effect observed in patients taking clindamycin and primaquine is a vesicular, desquamating, or ulcerating rash. Anemia is a frequent problem as well, which is likely related to the strong oxidative effects of primaquine that lead to its contraindication in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. The primaquine component of this treatment combination may lead to methemoglobinemia as well. Less common side effects include nausea and vomiting, neutropenia, and gastrointestinal complaints.

Dapsone and TMP

The combination of dapsone and TMP has been shown to possess similar efficacy to TMP-SMX in the treatment of mild to moderate PCP, with significantly fewer treatment-limiting unfavorable effects. Of patients with mild to moderate PCP, > 90% may be expected to respond to treatment with dapsone and TMP.

Adverse reactions to this combination regimen seem to occur at a much lower rate than to either pentamidine or TMP-SMX. Side effects requiring termination of treatment have occurred in < 10% of patients receiving dapsone and TMP. In clinical trials, the major side effects most commonly include rash (occasionally requiring discontinuation of therapy), elevated hepatic transaminases, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, and methemoglobinemia with serum levels that can exceed 20%. Of note, dapsone is a potent oxidant, an effect that can cause severe hemolysis in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, and it should be used with caution in this population of patients.

Corticosteroids

The use of corticosteroids has unquestionably been shown to reduce mortality by ~ 50% in patients with moderate to severe PCP. In addition, the need for mechanical ventilation is dramatically reduced in this group of patients. Patients with mild to moderate PCP have not demonstrated benefit from the use of adjuvant corticosteroid use. The suppression of the host inflammatory response to the presence of P carinii infection is thought to be the mechanism of the beneficial effect of corticosteroids. Corticosteroid use may exacerbate mucocutaneous herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus infections, and the lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Prognosis

Many clinical markers or scoring systems have been suggested to diagnose and predict outcome in PCP. Most if not all of these factors have been shown to have little value in the management of disease. The degree of hypoxia is an important prognostic factor that affects recommended treatment. The adjuvant use of corticosteroids and choice of treatment regimen should be based on whether the disease is classified as mild to moderate (PaO2 > 70 mm Hg and P[A-a]O = 35 mm Hg) or moderate to severe (PaO2 < 70 mm Hg or P[A-a]O = 35 mm Hg). However, it is probably better to err on the side of using corticosteroids.

Prevention & Control

Prophylaxis for PCP has clearly been shown to be effective in reducing the incidence of disease and improving survival in patients at risk for developing the disease (Box 4). No chemoprophylactic treatment regimen has been shown to be more effective than TMP-SMX. In addition, TMP-SMX provides protection against the bacteria that cause community-acquired pneumonia, as well as against toxoplasmosis. Aerosolized pentamidine isethionate and dapsone with or without pyrimethamine or TMP should continue to be regarded as second-line agents in the prevention of PCP.

TMP-SMX

No drug regimen has been shown to be more effective for preventing PCP in immunocompromised patients than TMP-SMX. Several primary and secondary prevention trials have proven that TMP-SMX is superior to aerosolized pentamidine isethionate and dapsone in patients who tolerate the drug. Patients who have experienced an initial episode of PCP have a more than threefold greater risk of developing a subsequent recurrence at 18 months while receiving aerosolized pentamidine isethionate than while receiving TMP-SMX. The use of TMP-SMX three times weekly seems to afford protection against P carinii infection that is equal to that from daily treatment.

Of patients receiving prophylaxis against PCP with TMP-SMX, = 75% may not tolerate the drug. Because TMP-SMX is cheaper and more effective than other treatment options, desensitization protocols have been used to allow some patients who were previously intolerant to TMP-SMX to continue taking the drug. Several published reports indicate that the majority of patients with previous mild to moderate adverse reactions and some with severe anaphylactic responses to TMP-SMX may be safely and successfully desensitized with oral protocols. Thus, most patients who were previously thought to be unable to tolerate TMP-SMX for prophylaxis against PCP may be safely and effectively desensitized with oral desensitization protocols and continue to take TMP-SMX. Some physicians have recommended that all patients who started treatment with SMX should use a desensitization protocol, thus preventing many allergic reactions.

Dapsone

Dapsone with or without pyrimethamine or TMP is as potent as inhaled pentamidine isethionate but less effective than TMP-SMX in the primary prevention of PCP in HIV-infected individuals. Dapsone is also poorly tolerated, with only 25% of patients in one randomized trial who were able to complete the daily treatment regimen. Dapsone does have the advantage over pentamidine isethionate in efficacy against Toxoplasma infections.

Twice weekly dapsone and pyrimethamine appears to be an effective and perhaps better tolerated alternative to daily dosing regimens. Toxicities associated with prophylactic dapsone are the same as those listed in the treatment section.

Aerosolized Pentamidine Isethionate

Pentamidine isethionate delivered once monthly via an ultrasonic nebulizer is a reasonable but less effective alternative to oral systemic therapy in PCP prophylaxis. Aerosolized pentamidine isethionate is very well tolerated, with < 15% of patients being unable to tolerate treatment. Unfortunately, aerosolized pentamidine isethionate is more likely to result in extrapulmonary P carinii infection because very little inhaled drug is absorbed systemically. Aerosolized pentamidine isethionate has been shown to reduce the sensitivity of diagnostic procedures used in the diagnosis of PCP as well.

When adverse effects are encountered with inhaled pentamidine isethionate, they are mainly limited to a dry cough and bad taste in the mouth. Spontaneous pneumothorax is a potentially dangerous effect of aerosolized pentamidine isethionate. The small amount of systemic absorption may occasionally result in rash, renal impairment, and pancreatitis. Use of an albuterol inhaler before the nebulized pentamidine isethionate is recommended as routine by some to prevent bronchospasm and to promote better penetration of the drug.

Links

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172927/pdf/100401.pdf

http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/615195