Systemic mycoses, such as histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, blastomycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, and sporotrichosis, are caused by primary or “pathogenic” fungi that can cause disease in both healthy and immunocompromised individuals. In contrast, mycoses caused by opportunistic fungi such as Candida albicans, Aspergillus spp., Trichosporon, Torulopsis (Candida) glabrata, Fusarium, Alternaria, and Mucor are generally found only in the immunocompromised host.

Advances in medical technology, including organ and bone marrow transplantation, cytotoxic chemotherapy, the widespread use of indwelling intravenous (intravenous) catheters, and the increased use of potent, broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents, have all contributed to the dramatic increase in the incidence of fungal infections worldwide.

Specific fungal infections

Candida infections

Eight species of Candida are regarded as clinically important pathogens in human disease: C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, C. stellatoidea, C. guilliermondi, C. lusitaniae, and C. glabrata.

Hematogenous Candidiasis

- Hematogenous candidiasis describes the clinical circumstances in which hematogenous seeding to deep organs such as the eye, brain, heart, and kidney occurs.

- Candida is generally acquired via the gastrointestinal tract, although organisms may also enter the bloodstream via indwelling intravenous catheters. Immunosuppressed patients, including those with lymphoreticular or hematologic malignancies, diabetes, immunodeficiency diseases, or those receiving immunosuppressive therapy with high-dose corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, antineoplastic agents, or broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents are at high risk for invasive fungal infections. Major risk factors include the use of central venous catheters, total parenteral nutrition, receipt of multiple antibiotics, extensive surgery and burns, renal failure and hemodialysis, mechanical ventilation, and prior fungal colonization.

- Three distinct presentations of disseminated C. albicans have been recognized: (1) the acute onset of fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, and occasionally chills or hypotension (similar to bacterial sepsis); (2) intermittent fevers; (3) progressive deterioration with or without fever; and (4) hepatosplenic candidiasis manifested only as fever while the patient is neutropenic.

- No test has demonstrated reliable accuracy in the clinical setting for diagnosis of disseminated Candida infection. Blood cultures are positive in only 25% to 45% of neutropenic patients.

- Treatment of candidiasis is presented in Table Therapy of Invasive Candidiasis.

- In patients with an intact immune system, removal of all existing central venous catheters should be considered.

- Amphotericin B may be switched to fluconazole (intravenous or oral) for completion of therapy.

- Lipid-associated formulations of amphotericin B, liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) and amphotericin B lipid complex (Abelcet) have been approved for use in proven cases of candidiasis; however, patients with invasive candidiasis have also been treated successfully with amphotericin B colloid dispersion (Amphotec or Amphocil). The lipid-associated formulations are less toxic but as effective as amphotericin B deoxycholate.

- Many clinicians advocate early institution of empiric intravenous amphotericin B in patients with neutropenia and persistent fever (more than 5 to 7 days). Suggested criteria for the empiric use of amphotericin B include (1) fever of 5 to 7 days’ duration that is unresponsive to antibacterial agents, (2) neutropenia of more than 7 days’ duration, (3) no other obvious cause for fever, (4) progressive debilitation, (5) chronic adrenal corticosteroid therapy, and (6) indwelling intravascular catheters.

Aspergillus infections

- Of more than 300 species of Aspergillus, three are most commonly pathogenic: A. fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. niger.

- Aspergillosis is generally acquired by inhalation of airborne conidia that are small enough (2.5 to 3 mm) to reach the alveoli or the paranasal sinuses.

Superficial infection

Superficial or locally invasive infections of the ear, skin, or appendages can often be managed with topical antifungal therapy.

| TABLE. Therapy of Invasive Candidiasis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Allergic bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

- Allergic manifestations of Aspergillus range in severity from mild asthma to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis characterized by severe asthma with wheezing, fever, malaise, weight loss, chest pain, and a cough productive of blood-streaked sputum.

- Therapy is aimed at minimizing the quantity of antigenic material released in the tracheobronchial tree.

- Antifungal therapy is generally not indicated in the management of allergic manifestations of aspergillosis, although some patients have demonstrated a decrease in their glucocorticoid dose following therapy with itraconazole.

Aspergilloma

- In the nonimmunocompromised host, Aspergillus infections of the sinuses most commonly occur as saprophytic colonization (aspergillomas, or «fungus balls») of previously abnormal sinus tissue. Treatment consists of removal of the aspergilloma. Therapy with glucocorticoids and surgery is generally successful.

- Although intravenous amphotericin B is generally not useful in eradicating aspergillomas, intracavitary instillation of amphotericin B has been employed successfully in a limited number of patients. Hemoptysis generally ceases when the aspergilloma is eradicated.

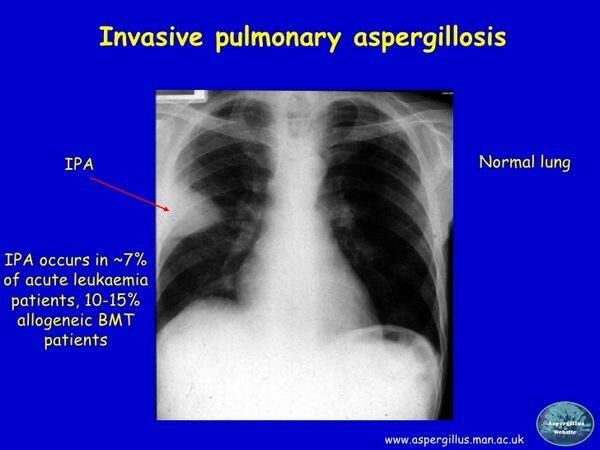

Invasive Aspergillosis

Patients often present with classic signs and symptoms of acute pulmonary embolus: pleuritic chest pain, fever, hemoptysis, a friction rub, and a wedge-shaped infiltrate on chest radiographs.

Diagnosis

- Demonstration of Aspergillus by repeated culture and microscopic examination of tissue provides the most firm diagnosis. A rapid test to detect galactomannan antigen in blood was recently approved in the United States.

- In the immunocompromised host, aspergillosis is characterized by vascular invasion leading to thrombosis, infarction, and necrosis of tissue.

Treatment

- Antifungal therapy should be instituted in any of the following conditions: (1) persistent fever or progressive sinusitis unresponsive to antimicrobial therapy; (2) an eschar over the nose, sinuses, or palate; (3) the presence of characteristic radiographic findings, including wedge-shaped infarcts, nodular densities, or new cavitary lesions; or (4) any clinical manifestation suggestive of orbital or cavernous sinus disease or an acute vascular event associated with fever. Isolation of Aspergillus sp. from nasal or respiratory tract secretions should be considered confirmatory evidence in any of the previously mentioned clinical settings.

- Intravenous amphotericin B remains the preferred therapy, at least initially, in acutely ill patients. Since Aspergillus is only moderately susceptible to amphotericin B, full doses (1 to 1.5 mg/kg/day) are generally recommended, with response measured by defervescence and radiographic clearing. The lipid-based formulations may be preferred as initial therapy in patients with marginal renal function or in patients receiving other nephrotoxic drugs.

- Itraconazole should be reserved as a second-line agent for patients intolerant of or not responding to high-dose amphotericin B. If itraconazole is used, a loading dose of 200 mg three times daily with food for 2 to 3 days should be employed, followed by itraconazole, 200 mg twice daily with food, for a minimum of 6 months.

- Caspofungin is indicated for treatment of invasive aspergillosis in patients who are refractory to or intolerant of other therapies such as amphotericin B and/or itraconazole.

- The use of prophylactic antifungal therapy to prevent primary infection or reactivation of aspergillosis during subsequent courses of chemotherapy is controversial.