Enteric cryptosporidiosis is the most common clinical presentation in patient populations. In addition, immunocompromised patients may present with cholecystitis or respiratory infections attributed to C parvum (Box 1). Asymptomatic infection has also been reported.

ENTERIC CRYPTOSPORIDIOSIS

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

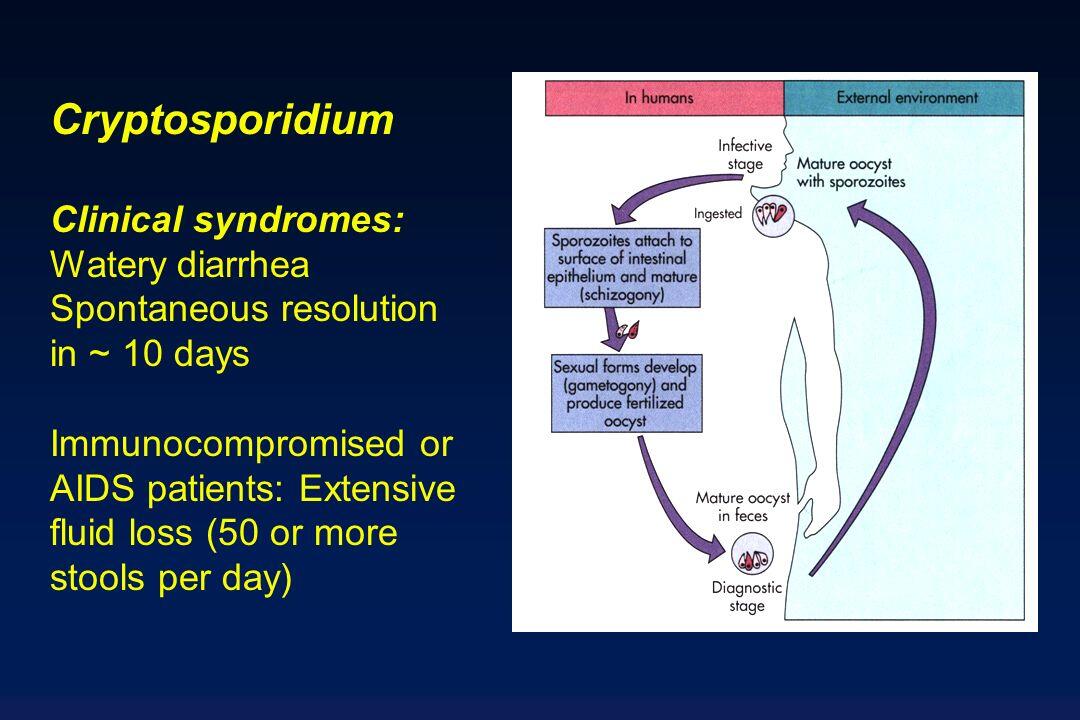

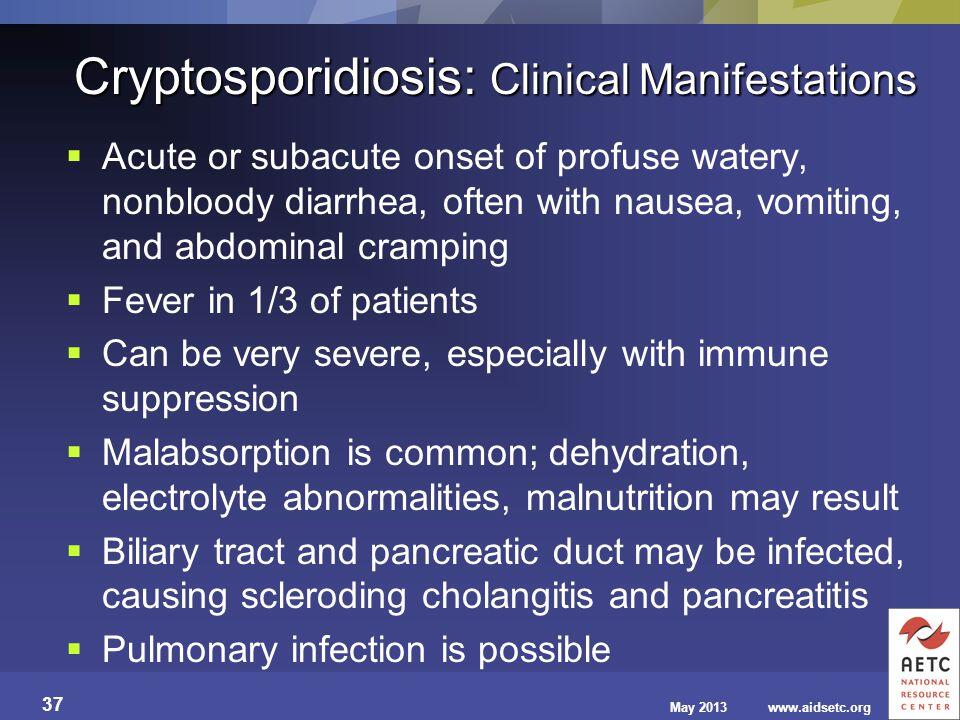

An average of 5-7 days passes from oocyst ingestion to symptom onset. Symptoms are similar in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients but are prolonged and considerably more severe in compromised patients. Patients complain of watery diarrhea in variable quantities of = 25 L/day leading to significant dehydration. Abdominal cramps, malaise, low-grade fever, and anorexia are frequently reported. Nausea, vomiting, myalgia, headache, and weight loss may also occur. Symptoms are usually self-limited in immunocompetent hosts, lasting 5-14 days, although cases lasting several months have been reported in normal hosts. Oocysts can still be found in stool 2 weeks after symptom resolution.

Laboratory Findings

Stool samples are generally negative for erythrocytes and leukocytes but can be streaked with mucous. Leukocytosis and eosinophilia are rare. After prolonged illness, malabsorption of fat, D-xylose, and B12 can be measured.

Imaging

Abdominal films are nonspecific, revealing mucosal thickening and disordered motility. Endoscopy shows only focal nonspecific atrophy.

Differential Diagnosis

In the immunocompetent host, C parvum infection may present similarly to Shigella, Salmonella, and Campylobacter spp., as well as Clostridium difficile and Giardia spp., in patients with an appropriate history. Similar presentations occur with Entamoeba histolytica and other coccidia, and in immunodeficient patients, diagnoses of cytomegalovirus, Mycobacterium avium, and microsporidia should be entertained.

Complications

Toxic megacolon and reactive arthritis involving the wrists, hands, knees, ankles, or feet have been reported in association with cryptosporidiosis. Pancreatitis has also been reported in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts presenting with cryptosporidiosis.

CHOLECYSTITIS

Up to 10% of AIDS patients with cryptosporidiosis present with cholecystitis. Cryptosporidial cholecystitis has thus far been diagnosed only in AIDS patients.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Patients present with fever, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting with or without associated diarrhea.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory studies reveal elevated alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels.

Imaging

Imaging with ultrasound or computed tomography usually shows an enlarged gallbladder with thickened walls and dilated ducts but may be normal in 25% of infected patients. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography can reveal common bile duct beading or papillary stenosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Microsporidial and cytomegalovirus infections may have similar presentations in patients with AIDS.

Complications

Cryptosporidial cholecystitis has been complicated by pancreatitis, cholangitis, hepatitis, and chronic gallbladder carriage.

RESPIRATORY INFECTION

C parvum has rarely been identified in biopsy and lavage specimens of immunodeficient patients who present with dyspnea, hoarseness, wheezing, or cough as well as symptoms of laryngotracheitis and sinusitis. Chest films are generally normal or show modest infiltrates and increased bronchial markings. The respiratory syndrome has not yet been directly associated with C parvum diarrheal illness.

Diagnosis

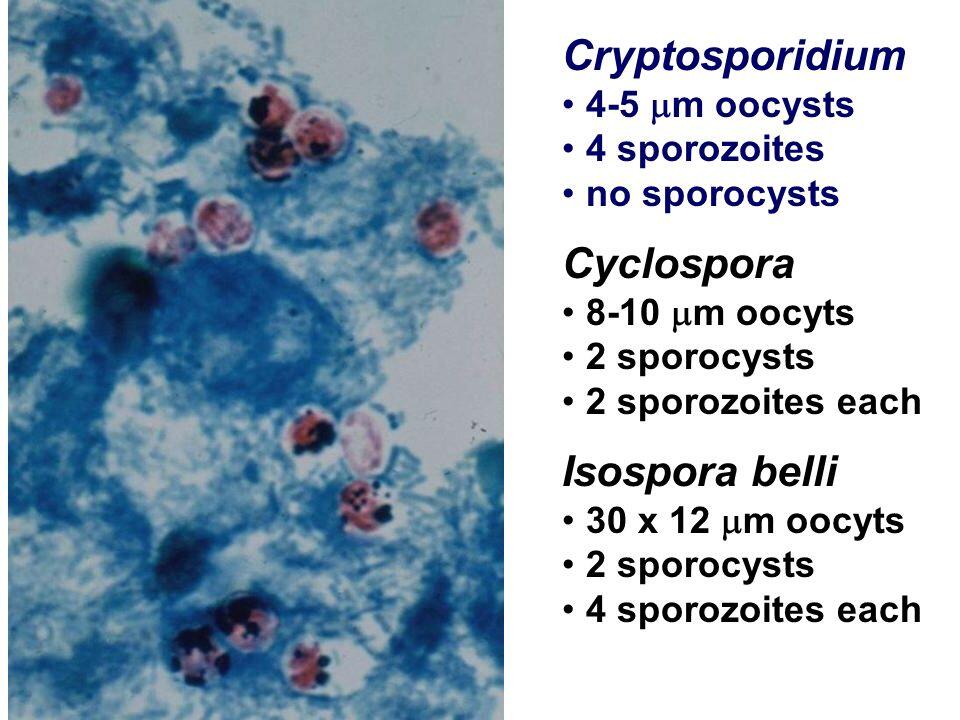

The majority of diagnoses of C parvum infection are made by identification of the organism in stool specimens (Table 1). Stool should be examined while it is fresh or fixed in 10% formalin or polyvinyl alcohol. Oocysts can be identified by light microscopy without specific staining but are more readily seen with modified acid-fast staining. Phase-contrast microscopy reveals birefringent oocysts. Oocysts in duodenal aspirates or respiratory secretions can be similarly identified. Submitting three to four separate stool samples has been recommended for increased diagnostic yield. However, in a study of AIDS inpatients, one stool specimen resulted in 96% sensitivity, increasing to 100% with only two specimens. Orders should specify suspected C parvum because most laboratories do not routinely use acid-fast staining.

Immunofluorescence and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay techniques are more sensitive and specific methods of diagnosis. Sensitivities of 93-100% and specificities of 99-100% have been reported for various direct immunofluorescent-antibody assays. The available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay techniques have 72-100% sensitivity and 98-100% specificity. The clinical utility of polymerase chain reaction analysis is still developing.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of intestinal biopsy specimens reveals basophilic organisms on the brush border that appear to project into the lumen because of the intracellular but extracytoplasmic location of the organism. Direct immunofluorescence can also be used on these biopsy specimens, and electron microscopy provides greater detail. However, the invasiveness of biopsy is rarely warranted and is not 100% sensitive.

Serologic antibody identification is available for C parvum infection but is still investigational and not clinically useful for diagnosis due to the persistence of antibody after infection. It is valuable as an epidemiologic tool, however.

Treatment

No reliable treatment is available at this time for cryptosporidiosis (Box 2). Supportive care with fluids and antidiarrheal agents can be offered while awaiting resolution in immunocompetent hosts or while addressing the underlying etiology of immunosuppression in compromised hosts. Paromomycin sulfate is currently the drug of choice for C parvum, surpassing spiramycin, for which there are no controlled studies. Paromomycin treatment is well tolerated by patients, but relapse is common even on therapy. For those patients relapsing off of therapy, however, 80% will again have a good response when they are back on paromomycin sulfate. Initial reports on the efficacy of a special lactose-free preparation of azithromycin have been promising. Hyperimmune bovine colostrum has been helpful in decreasing symptoms despite the persistence of oocyst shedding. Bovine transfer factor isolated from infected calf lymph node suspensions has been shown to attenuate symptoms, and octreotide has been similarly helpful. For all of the above therapeutic modalities, large randomized studies are needed for better understanding and documentation of effect.

Prognosis

Although cryptosporidiosis is self-limited in immunocompetent patients, patients with AIDS with enteric cryptosporidiosis present with disease, the severity of which is related to the degree of immunosuppression. In one series of patients with AIDS, 29% of cases were transient, 60% chronic, 8% fulminant, and 4% asymptomatic. Mean survival in these patients was 25 weeks.

Prevention & Control

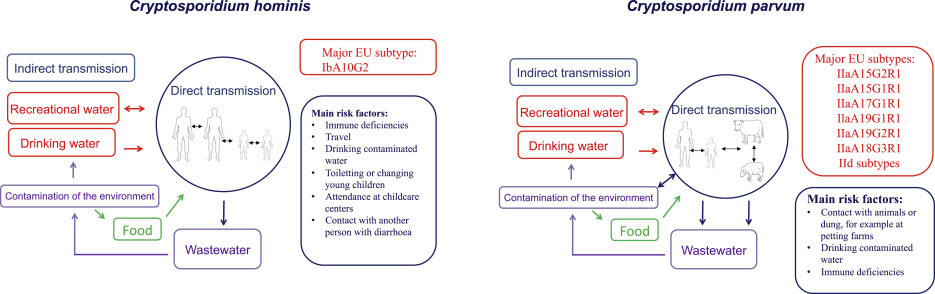

C parvum oocysts are 30-fold more resistant to chlorine than are Giardia cysts. Oocysts are killed in water kept above 65°C for 30 min as well as water boiled for 1 min at any altitude. Oocyst death is also reported in water kept at < 20°C for 30 min, although more recent information suggests greater resistance to freezing than previously thought (Box 3).

Enteric precautions and good hygiene should reduce most person-to-person transmission as well as animal-to-human exposures because family contacts account for = 50% of secondary cases. Also, apple juice and cider should be pasteurized or boiled before consumption. No prophylactic regimen for patients with AIDS is yet available, although paromomycin sulfate and azithromycin are being studied. Immunocompromised patients should be instructed to drink bottled or boiled water if water supplies are suspect.