Within the last decade, the AIDS epidemic has heightened awareness of several gastrointestinal spore-forming protozoan pathogens. The genera Cryptosporidium, Isospora, and Cyclospora are members of the subclass Coccidia and phylum Apicomplexa; the microsporidia are a group of organisms belonging to the phylum Microspora. The spectrum of disease caused by these protozoans goes beyond gastrointestinal manifestations, and the significance of these protozoan infections is becoming increasingly appreciated in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent hosts.

CRYPTOSPORIDIUM

Essentials of Diagnosis

- Key signs and symptoms include dehydration with watery diarrhea of variable quantity.

- Waterborne transmission is the most common mode of oocyst transmission.

- Patients at risk for person-to-person transmission include household contacts, sexual contacts, health care workers, and children in day care.

- Symptoms are prolonged and more severe in immunocompromised patients.

- Acid-fast staining of fixed stool specimens allows identification of oocysts; immunofluorescence and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay techniques are also available.

General Considerations

Epidemiology

Cryptosporidium spp. were first described at the beginning of this century but were not reported as human pathogens until 1976. Cryptosporidium infection is present worldwide with 250 million-500 million annual cases. Increased infection rates occur during warm, humid months. In industrialized nations, oocyst passage is prevalent in 1-3% of the population, compared with 5-10% oocyst passage in less-developed nations. This difference has been attributed to existence in the developing countries of conditions such as poor sanitation, crowded households, and nearby animal reservoirs. Industrialized nations report an increased prevalence in rural areas, whereas less-developed nations have a higher urban prevalence. The significance of cryptosporidiosis may be underestimated because the seroprevalence in industrialized nations has been reported to be = 35%. In developing nations, seroprevalence has been reported to be = 100%. Patients with AIDS with diarrhea have an 11-21% oocyst passage prevalence in developed nations compared with a rate of = 50% in Africa and Haiti. Chronic intestinal cryptosporidiosis that lasts > 1 month has been classified as an AIDS-defining opportunistic infection.

Transmission of oocysts occurs by person-to-person, animal-to-person, and environmental contacts. Those at risk for person-to-person transmission include household members, sexual partners, health workers, and children in day care. Nineteen percent of household contacts of infected patients have been diagnosed with secondary infection. Household pets, laboratory animals, and farm animals have all been associated with transmission to humans. Nosocomial infection has also been reported.

Waterborne oocyst transmission is considered the most important mode of transmission and is associated with the largest outbreaks. The initial cases of waterborne transmission were described in 1983, in Finnish individuals with diarrhea who had traveled to St. Petersburg (then Leningrad), Russia. Subsequently, other cases of traveler’s diarrhea have been attributed to cryptosporidiosis. Many common source outbreaks have been described in Great Britain and the United States, the largest of which occurred in Milwaukee in 1993, affecting 403,000 people. Surface runoff from cow pastures was identified as the contaminating source of oocysts. Unboiled well water has also been implicated in transmission. Cryptosporidiosis related to apple cider has been associated with use of fallen apples in contaminated cow pastures. Oocysts, which survive well in cold, moist environments, are found in 65-87% of surface water. In one study, oocysts were found in 27% of drinking water samples from 66 inspected treatment plants, confirming the resistance of oocysts to current water treatment methods.

Microbiology

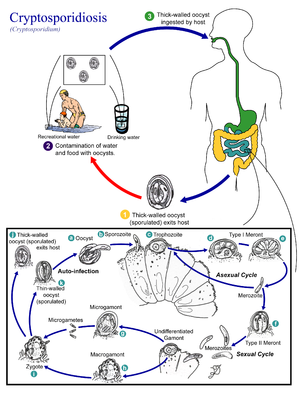

Cryptosporidium parvum is the species of this intracellular coccidian protozoan parasite that is responsible for illness in humans. Its life cycle occurs within a single host, beginning as an ingested thick-walled, round oocyst measuring 2-6 um in diameter. Excystation, induced by enzymes and bile salts found in the small intestine, releases four motile sporozoites that infect the small intestine. Further differentiation and division occur within an intracellular but extracytoplasmic vacuole of the enterocyte. Each sporozoite matures and divides asexually, releasing four to eight merozoites. The merozoite reinfects the small intestine or begins sexual maturation to a zygote and ultimately a fully sporulated oocyst. Approximately one of five oocysts is thin walled and reinfects the host; the remaining thick-walled oocysts are passed in stool to the environment. C parvum is unique in its ability to complete its life cycle within a single host. In particular, the autoinfectivity of the merozoites and thin-walled oocysts allows C parvum to perpetuate infection without subsequent environmental exposures.

Pathogenesis

The mechanism of disease associated with C parvum infection is unknown. As few as 30 oocysts have been found to cause infection in healthy volunteers, with a mean infective dose of 132 oocysts. The organism is limited to the intestine and appendix in the immunocompetent host, but it may be found throughout the gastrointestinal tract, in the hepatobiliary system, and in the respiratory tract of immunocompromised patients.

The resulting diarrhea is postulated to be either secretory (ie, caused by an unidentified toxin) or osmotic (ie, caused by malabsorption from intestinal villi injury). Histologic findings include atrophy, blunting, fusion, or loss of villi. Crypt hyperplasia is seen, and the lamina propria of the intestine has an inflammatory infiltrate.

The immune response in cryptosporidiosis is also poorly understood. Patients with a variety of immune deficiencies, including both T-cell abnormalities and ?-globulin deficiencies, have prolonged and more severe infections. Acquired immunity can prevent reinfection and limit primary infection, but the mechanism of protection is not entirely understood. Selective antibodies may inhibit an important attachment step. Bovine colostrum containing anti-C parvum antibodies limited infection in immunodeficient patients, but similar colostrum without antibodies did the same in experimental mouse infections. Further, patients with AIDS have been shown to mount an antibody response yet still be unable to clear the infection. This response lends support to other evidence suggesting the importance of adequate CD4 cells in addition to immunoglobulin A antibodies for protection. The presence of particular cytokines may be important in this interaction. Human breast milk does not confer protection from infection.

Cryptosporidium: Clinical Syndromes

CLINICAL SYNDROMES IN NON-HIV-INFECTED PATIENTS

Microsporidial infection in non-HIV-infected patients is rare, with < 20 cases reported. Central nervous system, corneal, muscular, enteric, and respiratory infections have all been identified (Box 9).

Central nervous system infections have been reported in two immunocompetent children presenting with fever, loss of consciousness, headache, and convulsions, as well as hepatomegaly. E cuniculi was isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid and the urine. Computed tomography of the brain and electroencephalography were normal. Corneal infection has been caused by Nosema spp., Microsporidium ceylonensis, and Microsporidium africanum. Patients have presented with decreased visual acuity, conjunctivitis, and corneal ulcers. Corneal biopsy reveals the organism.

Patients presenting with generalized muscle weakness have been diagnosed with myositis caused by Pleistophora spp. Laboratory tests revealed normal creatine kinase levels, and electromyograms showed myopathy. Muscle biopsies revealed scarring, fibrosis, inflammation, and Pleistophora infiltrate. Self-limited diarrhea caused by E bieneusi has been reported in an immunocompetent host. A patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia who had undergone allogenic bone marrow transplant was recently shown on autopsy to have microsporidial infection along with Candida tropicalis infection within lung sections.

CLINICAL SYNDROMES IN HIV-INFECTED PATIENTS

The most common manifestation of microsporidial infection in HIV-infected patients is enteric disease, but other recognized syndromes include biliary infection, pulmonary infection, keratoconjunctivitis, and myositis (Box 10).

GASTROINTESTINAL INFECTION

E bieneusi and S intestinalis are the most common etiologic agents identified in patients presenting with chronic diarrhea due to microsporidia. However, there is one case report of E cuniculi identified in intestinal infection.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms can persist over months and are associated with anorexia and a 10-20% weight loss. The diarrhea is usually loose and watery, with patients reporting 1-20 stools/day. The diarrhea is worse in the mornings and exacerbated by eating. A crampy abdominal pain can precede defecation. Nausea and vomiting are rarely present, and patients are afebrile.

Laboratory Findings

Stool specimens are negative for leukocytes or erythrocytes. Serum electrolytes can reveal low potassium, magnesium, and zinc. Malabsorption is indicated by abnormal D-xylose absorption, low B12 levels, and increased fecal fat.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes C parvum and other coccidial protozoa. Coinfection with Mycobacterium avium complex, Giardia spp., and C parvum in the small bowel and cytomegalovirus and C parvum in the large bowel has been reported.

Complications

Complications of gastrointestinal infection include biliary disease by direct extension and respiratory infection from aspiration. Nephritis by hematogenous spread of S intestinalis has been documented, and S intestinalis has also been identified in a rectal ulcer. Mortality of enteric microsporidiosis has been reported at 56%.

BILIARY INFECTION

E bieneusi and S intestinalis, often associated with cryptosporidial coinfection, have been identified in patients presenting with symptoms of cholecystitis.

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms include right upper quadrant pain, concomitant diarrhea, and rarely jaundice.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory studies reveal elevated alkaline phosphatase and transaminase levels that are twice to three times normal. Bilirubin levels are usually normal. CD4 counts are < 50.

Imaging

Imaging studies using computed tomography, ultrasound, or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography reveal dilated ducts and gallbladder thickening with sludge.

PULMONARY INFECTION

E bieneusi has been found in bronchial lavage specimens of patients presenting with cough, dyspnea, wheezing, or sinusitis. Chest x-rays show interstitial infiltrates.

KERATOCONJUNCTIVITIS

E cuniculi and E hellem as well as S intestinalis have caused corneal infections in HIV-infected patients. Patients present with dry eyes, foreign-body sensation, or ocular pain. Blurred vision, excessive tearing, and photophobia have also been reported. Conjunctival hyperemia may be present, and slit-lamp exam reveals a diffuse, superficial punctate keratopathy. Microsporidial corneal infections have been associated with systemic disease with concomitant bronchiolitis, sinusitis, nephritis, cystitis and ureteritis, hepatitis, and peritonitis.

MYOSITIS

Pleistophora infection in immunocompromised patients presents similarly to that in immunocompetent patients as already described.

Diagnosis

The small size of the Microsporidium spore makes diagnosis difficult (Table 4). The sensitivity and specificity of different identification techniques are not known. Microsporidial spores are gram positive and birefringent, and they have a positive periodic acid-Schiff-staining polar body. Spores can be found in stool, duodenal aspirates, urine, respiratory secretions, and conjunctival scrapings. Diagnostic yield may be enhanced by collecting three stools daily over 3 subsequent days. Spore concentration and sedimentation techniques can increase yield. Weber’s modified trichrome, Gram, Giemsa, and chitin-binding fluorochrome stains have all been used successfully to identify spores. Diagnostic yield can be increased by preserving stool in formalin, pretreating in 10% potassium hydroxide, and centrifuging for 5 min before staining with the Weber’s modified trichrome stain. Biopsy specimens can be similarly stained, but sensitivity may be decreased due to normal-appearing mucosa. If < 25 spores are identified from a stool specimen per coverslip, the likelihood of identifying organisms by electron microscopy of a biopsy specimen is low. E bieneusi usually involves the distal duodenum and proximal jejunum, and S intestinalis can also involve the colon.

Electron microscopy can more readily identify the small spores and is useful in speciation. Immunofluorescence and polymerase chain reaction techniques are also valuable for speciation.

Treatment

Microsporidial treatment efficacy is anecdotal at this time (Box 11). Albendazole has had the best success thus far in alleviating gastrointestinal and biliary symptoms. However, eradication of spores is rare, and relapse occurs 1-2 months after completion of 4 weeks of albendazole. Metronidazole was reported to have a transient clinical response only, and atovaquone has had mixed results. Fumagillin, itraconazole, and fluconazole are currently being studied. Palliative treatment with octreotide and nutrition adjustments such as prescribing low-fat and simple carbohydrate diets may be beneficial.

Topical fumagillin and propamidine isethionate (0.1%) have been effective in treating microsporidial keratopathy. One case report suggests that itraconazole may be beneficial in this realm as well.

Prevention & Control

Control of microsporidial infection will be difficult to address until transmission is better understood (see Box 6). Bodily fluid precautions seem warranted to prevent fecal-oral and urinary-oral transmission. Disinfecting, boiling, and autoclaving may also be of benefit. The necessity of respiratory precautions and isolation is uncertain.

Table 1. Laboratory diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis.

- Oocysts are < 4-6 µm in diameter, round, and thick-walled, containing four sporozoites

- Oocysts are identified in stool, duodenal aspirates, bile, or respiratory secretions

- Stool should be fresh or fixed in 10% formalin or PVA and may be stained with modified acid-fast stain.

- Intestinal biopsy shows intracellular but extracytoplasmic sporozoites on the brush border staining basophilic with H & E staining

- Phase contrast microscopy shows birefringent oocysts

- ELISA and immunofluorescent assays are more sensitive and specific methods of diagnosis

- PCR and serology studies are not clinically useful at this time

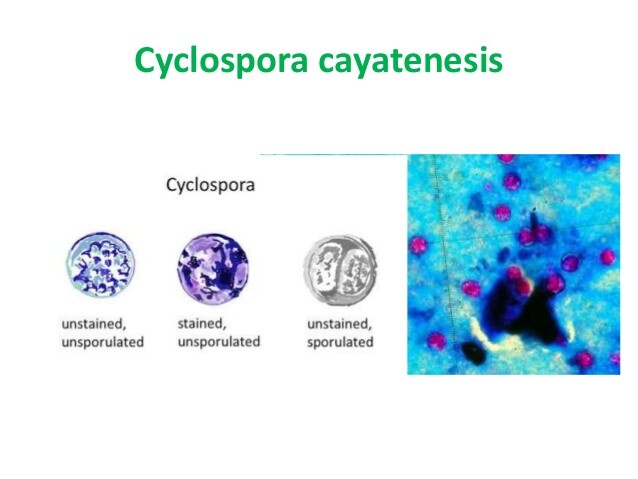

Table 2. Laboratory diagnosis of Cyclospora infection.

- Oocysts are 10-µm-diameter nonrefractile spheres that contain clusters of refractile globules

- Oocysts can be identified in fresh or iodine-preserved stool, duodenal aspirates, or small-bowel biopsies by modified acid-fast staining or safranin staining

- Oocysts autofluoresce blue under UV light, using a 365-nm excitation filter

- Antibody titers to Cyclospora infection rise during convalescence but are not clinically useful

Table 3. Laboratory diagnosis of isosporiasis.

- Unsporulated oocysts are 20-33 µm × 10-19 µm and contain one or two immature sporonts

- When mature, the oocyst has two sporocysts, each with four sporozoites

- The thin, transparent oocyst wall can be detected on wet mount or by modified acid-fast or trichrome staining

- Oocysts autofluoresce under UV light by using a 450- to 490-nm excitation filter

- Duodenal string test or colonoscopy aspiration may be helpful

Table 4. Laboratory diagnosis of microsporidiosis.

- 1- to 2-µm, gram-positive, birefringent, PAS-positive ovoid spore

- By spore concentration and sedimentation techniques, spores can be identified with Weber’s modified trichrome, Gram, giemsa, or chitin-binding fluorochrome stains

- Electron microscopy, immunofluorescence, and PCR techniques are valuable for speciation

BOX 1. Cryptosporidiosis Syndromes

Enteric

Cholecystitis

Respiratory

More Common

- Watery diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Fever

- AIDS patient

- Right upper-quadrant pain

- Fever

- Nausea/vomiting

- High alkaline phosphatase

- Immunocompromised

- Cough

- Dyspnea

- Hoarseness

Less Common

- Malaise

- Weight loss

- Myalgia

- Headache

- Malabsorption

- Diarrhea

- High bilirubin

- Sinusitis

- Laryngotracheitis

BOX 2. Treatment of Cryptosporidiosis1

Adults

Children

First Choice

- Paromomycin, 500-750 mg orally four times daily

- Paromomycin, 25-35 mg/kg/d divided in 3 doses

Second Choice

- Azithromycin, 900 or 1200 mg orally once daily × 2 weeks

- None

Palliation

- Bovine transfer factor

- Hyperimmune bovine colostrum

- Octreotide

All treatments are investigational, without Food and Drug Administration approval.

BOX 3. Prevention & Control of Cryptosporidiosis

Prophylactic Measures

- Avoid contacts — sick animals and humans

- Enteric precautions

- Immunocompromised patients should drink boiled or bottled water if water supply is suspect

- Halogenation is not effective

- Water should be boiled for 1 min

Isolation Precautions

- No specific measures

- Good hygiene

BOX 4. Cyclosporiasis Syndromes

More Common

- Cyclical diarrhea

- Fatigue

- Anorexia

Less Common

- Dyspepsia

- Nausea

- Abdominal cramps

- Weight loss

- Vomiting

- Myalgia/arthralgia

BOX 5. Treatment of Cyclosporiasis

Adults

Children

First Choice

- TMP/SMX 160/800 mg orally four times daily × 10 d for initial infection

- TMP, 5 mg/kg; SMX, 25 mg/kg orally twice daily × 7 d

- TMP/SMX 160-800 mg — one tablet orally 3×/wk for prophylaxis

Second Choice

See text for possible alternatives

BOX 6. Prevention & Control of Cyclospora and Isospora spp. and Microsporidia

Prophylaxis Measures

- No proven established methods

- Enteric precautions

- Immunocompromised patients should drink boiled or bottled water if water supply is suspect

- TMP/SMX usage may be beneficial in patients with AIDS for prophylaxis of Cyclospora and Isospora infection

- Bodily fluid precautions may be important in microsporidial infection

- Agricultural measures to decrease water-borne contamination of raspberries are ongoing

Isolation Precautions

- No specific measures

- Good hygiene

BOX 7. Isosporiasis Syndromes

More Common

- Diarrhea

- Malaise

- Anorexia

Less Common

- Abdominal cramps

- Weight loss

- Headache

- Vomiting

- Flatulence

- Chronic diarrhea

- Eosinophilia

- Malabsorption

BOX 8. Treatment of Isosporiasis

Adults

Children

First Choice

TMP-SMX 160/800 orally four times daily × 10 d

TMP, 5 mg/kg; SMX, 25 mg/kg orally twice daily × 7 d

Second Choice

Pyrimethamine, 75 mg orally once daily × 10 d

Prophylaxis in AIDS

- TMP-SMX, 160/800 orally once daily 3×/wk

- Pyrimethamine/sulfadoxine, 25/500 orally once daily 3×/wk

- Pyrimethamine, 25 mg orally daily

BOX 9. Microsporidiosis in Non-HIV Patients

E cuniculi

Nosema spp.

Pleistophora spp.

E bieneusi

Signs & Symptoms

- Fever

- Loss of consciousness

- Headaches

- Convulsions

- Hepatomegaly

- Decreased visual acuity

- Conjunctivitis

- Corneal ulcer

- Generalized muscle weakness

- Self-limited diarrhea

BOX 10. Microsporidiosis Syndromes in HIV Patients (Syndrome and Organism)

Enteric

Biliary

Pulmonary

Keratitis/

Conjunctivitis

Myositis

E bieneusi

S intestinalis

E bienusi

S intestinalis

E bienusi

E cuniculi

E hellem

Pleistophora spp.

Signs & Symptoms

- Chronic diarrhea

- Weight loss of 10-20%

- Abdominal cramps

- Absence of fever

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Diarrhea

- Jaundice

- Cough

- Dyspnea

- Wheezing

- Sinusitis

- Dry eyes

- Foreign body sensation

- Ocular pain

- Tearing

- Photophobia

- Blurry vision

- Diffuse muscle weakness

BOX 11. Treatment of Microsporidiosis

Adults

Children

Intestinal and Biliary

Albendazole, 400 mg twice orally daily × 3-4 weeks

No data available for albendazole use for a prolonged period in children

Keratopathy

Topical fumagillin and propamidine isethionate 0.1%