Essentials of Diagnosis

- Leading cause of upper respiratory infection.

- Virus grows preferentially at 33 °C in diploid fibroblast cells.

- Typical illness includes rhinorrhea and low-grade fever but little evidence of lower respiratory illness.

General Considerations

Rhinoviruses are the most frequent cause of the common cold. One hundred two serotypes have been identified by neutralization with specific antisera, and additional strains have been isolated but are not yet typed.

Epidemiology

Rhinoviruses can be transmitted by two mechanisms: aerosols and direct contact (eg, with contaminated hands or inanimate objects). Surprisingly, aerosols may not be the major route, and hands appear to be an important vector. Rhinoviruses can be recovered from the hands of 40-90% of persons with colds and from 6-15% of inanimate objects around them. The virus can survive on these objects for many hours.

Rhinoviruses produce clinical illness in only half of those infected, and thus many asymptomatic individuals are capable of spreading the virus. Rhinovirus “colds” affect people in temperate climates most frequently in the early fall, which may reflect the return to school rather than any change in the virus itself. Rates of infection are highest in infants and children, who are also the primary vector introducing colds into family units. Secondary infections occur in ~50% of family members, especially other children.

Although many different rhinovirus serotypes may be found in a given community, only a few predominate during a specific cold season. They tend to be the newly categorized serotypes, suggesting that a gradual antigenic drift occurs.

Microbiology

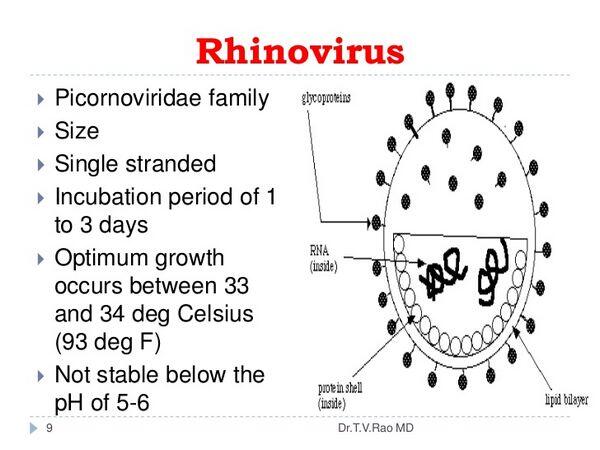

Many microbiological features of rhinoviruses are similar to those of enteroviruses (see site). As with all picornaviruses, the RNA of rhinoviruses is surrounded by a very small icosahedral capsid approximately 30 nm in diameter. The genome of these viruses resembles messenger RNA (mRNA). It is a single strand of (+)-sense RNA of ~7.2-8.5 kb. It encodes a polyprotein that is proteolytically cleaved to produce the enzymatic and structural proteins of the virus. In addition to the capsid proteins, these viruses encode at least one protease and an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. A virus-encoded protease blocks translation of cellular mRNA.

Pathogenesis

In contrast to enteroviruses, rhinoviruses are unable to replicate in the gastrointestinal tract. This contrast probably reflects differences in surface receptors between the two groups of viruses rather than degradation of rhinovirus by gastric acid. Also rhinoviruses replicate optimally at 33 °C, which may explain their predilection for the anterior nares.

At least 80% of the rhinoviruses share a common receptor, ICAM-1, which is a member of the immunoglobulin family and is expressed on epithelial, fibroblast, and lymphoblastoid cells.

Secretory and serum antibodies are generated in response to the rhinovirus and can be detected within a week of infection. No antigen is common to all rhinoviruses. Although secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA) is probably more important than serum antibody in preventing and controlling infection, its half-life is brief. A better correlate of immunity is the level of serum antibody that begins to wane ~18 months after infection.

Interferon, generated in response to the infection, may both limit the progression of the infection and contribute to the symptoms. The release of cytokines during inflammation can promote the spread of the virus by enhancing the expression of viral receptors. Cell-mediated immunity does not appear to play an important role in controlling rhinovirus infections.

Infection can be initiated by as little as one infectious viral particle. During the peak of illness, titers of 500 to 1,000 infectious virions are reached in nasal secretions. Most viral replication occurs in the nose, and the severity of symptoms correlates with the quantity (titer) of virus in nasal secretions. Biopsies of nasal mucosa taken during a “cold” reveal severe edema of the subepithelial tissue but minimal inflammatory cell response. Infected ciliated epithelial cells may be sloughed from the nasal mucosa.

Rhinovirus infection

Clinical Findings

Signs and Symptoms

Upper respiratory infections (URIs) caused by rhinoviruses usually begin with sneezing, soon followed by rhinorrhea (Box 1). The rhinorrhea increases and is then accompanied by nasal stuffiness. Mild sore throat also occurs, along with headache, malaise, and chills. The illness peaks in 3-4 days, but cough and nasal symptoms may persist for 7-10 days longer. High fever and shaking chills are not usual features of rhinovirus URIs.

Laboratory Findings

The clinical syndrome of the common cold is usually so characteristic that laboratory diagnosis is unnecessary. Rhinoviruses cause up to one half of URIs, but coronaviruses, parainfluenza viruses, and other agents also cause a sizable proportion of colds. Also at times it may be difficult to distinguish allergic rhinitis from an URI.

Nasal washings are the best type of clinical specimen for recovering the virus. Rhinoviruses grow in vitro only in cells of primate origin, with human diploid fibroblast cells (eg, WI-38) as the optimum system. As already stated, these viruses grow best at 33 °C, which is not the optimum temperature for any other clinically important viruses. Thus their isolation may require a separate incubator. Isolation in tissue culture occurs 4-5 days on average. The virus is identified by typical cytopathic effects and the demonstration of acid lability. Serotyping is rarely necessary but is done by using pools of specific neutralizing sera.

Serologic testing to document rhinovirus infection is not practical. No antigen is common to all rhinoviruses; thus it would be necessary to have the patient’s viral isolate or a prototype of the specific rhinovirus prevalent in the community in order to perform this kind of testing.

Differential Diagnosis

Several other viruses can cause similar syndromes, especially coronaviruses, adenoviruses, and parainfluenza viruses. Allergic rhinitis is not associated with fever and often is accompanied by an itching conjunctivitis. Also the peripheral blood may show eosinophilia.

Complications

In otherwise healthy individuals, rhinovirus illnesses are uncomplicated, but in those with chronic lung disease, exacerbations of bronchitis may occur. In severely immunocompromised patients, lower respiratory disease may occur.

Treatment

There is no specific therapy for rhinovirus (Box 2). Nasal vasoconstrictors may provide relief, but their use may be followed by rebound congestion and worsening symptoms. Antibacterial agents are not beneficial unless a true bacterial infection (eg, sinusitis) occurs. Even when nasal secretions have become purulent, a carefully performed Gram’s stain will usually show few if any bacteria. Rigorous studies of vitamin C therapy have not shown efficacy. Topical interferon provides antiviral activity but itself produces upper respiratory symptoms. Drugs that block viral attachment, penetration, or replication have been discovered and are being evaluated in clinical trials.

Prognosis

Because rhinovirus illnesses are usually uncomplicated, the prognosis for recovery is excellent, but as mentioned above in the complications section, exacerbations of chronic lung disease may occur, and fatal illnesses in immunocompromised patients have been reported.

Prevention & Control

There are three potential methods of prevention or control of rhinoviruses: vaccines, antiviral agents (especially interferon), and interruption of transmission (Box 3).

The multiple serotypes and apparent antigenic drift in rhinovirus antigens suggest that successful vaccines are unlikely. Formalin-inactivated, parenterally administered vaccines induce antibody in serum but not in nasal secretions and are not as useful as those given intranasally.

Prophylactic topical interferon is effective but associated with unacceptable side effects. Since transmission is person to person, infection may be reduced by minimizing finger to nose and hand to hand spread as well as by covering coughs and sneezes.

BOX 1. Rhinovirus Infection

Children

Adults

More Common

Upper respiratory infection

Upper respiratory infection

Less Common

BOX 2. Treatment of Rhinovirus Infection

First Choice

No specific antiviral Rx

Second Choice

Symptomatic treatment with vasoconstrictors and antipyretics

Pediatric

Considerations

Aspirin should be avoided

BOX 3. Control of Rhinovirus Infection

Prophylactic Measures

Avoid direct hand to hand and aerosol contact with symptomatic patients

Isolation Precautions

Vaccines not likely. Antiviral chemotherapy being evaluated

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)