Essentials of Diagnosis

- Vesiculopustular, generalized rash in a febrile child (varicella or chicken pox)

- Dermatomal pustular eruption in elderly or immunocompromised patient (herpes zoster or shingles)

- Multinucleated, giant epithelial cells with intranuclear inclusions in skin scrapings, tissue biopsy

- Slow growth of virus (5-7 days) in diploid fibroblast cells if fresh vesicles are cultured

- Detection of VZV antigen by immunofluorescence of skin vesicles (best diagnostic test)

General Considerations

Epidemiology

VZV infection, the cause of both varicella (chickenpox) and herpes zoster, is ubiquitous (Box 4). Nearly all persons contract chickenpox before adulthood, and 90% of cases occur before the age of 10. The virus is highly contagious, with attack rates among susceptible contacts of 75%. Varicella occurs most frequently during the winter and spring months. The incubation period is 11-21 days. The major mode of transmission is respiratory, although direct contact with vesicular or pustular lesions may result in transmission. Infectivity is greatest 24-48 h before the onset of rash and lasts 3-4 days into the rash. Virus is rarely isolated from crusted lesions.

Microbiology

VZV has the same general structure as HSV but has its own DNA sequence and envelope glycoproteins. Cellular features of infected cells, such as multinucleated giant cells and intranuclear eosinophilic inclusion bodies, are similar to those of HSV-infected cells. VZV is more difficult to isolate in cell culture than HSV and grows best but slowly in human diploid fibroblast cells.

Pathogenesis

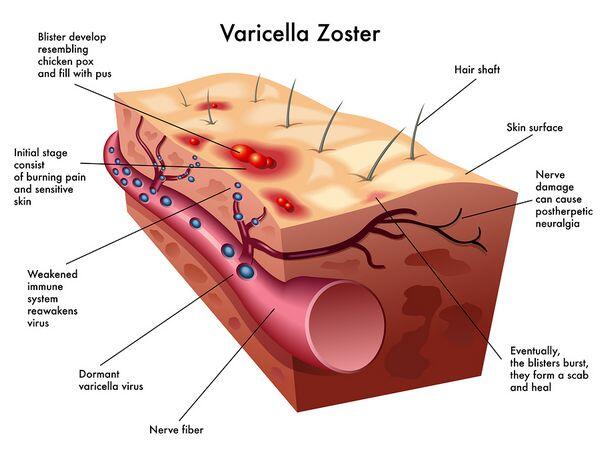

The viruses isolated from lesions of chickenpox and zoster (or shingles) are identical. Latency of VZV occurs in sensory ganglia, as shown by in situ hybridization detection of viral DNA in dorsal root ganglia of adults many years after varicella infection.

Immunity

Both humoral immunity and cell-mediated immunity are important factors in determining the frequency of reactivation and severity of varicella-zoster. Circulating antibody prevents reinfection, and cell-mediated immunity appears to control reactivation. In patients with depressed cell-mediated immune responses, especially those who have received bone marrow transplants or have Hodgkin’s disease, AIDS, or lymphoproliferative disorders, reactivation can occur, and be severe.

Clinical Findings

VZV produces a primary infection in healthy children which is characterized by a generalized vesicular rash termed chickenpox. Chickenpox lesions generally appear on the head and ears, then spread centrifugally to the face, neck, trunk, and extremities. Lesions appear in different stages of evolution; this characteristic was one of the major features to differentiate varicella from smallpox, in which lesions were concentrated on the extremities and appeared at the same stage of disease. Varicella lesions are pruritic, and the number of vesicles may vary from 10 to several hundred. Involvement of mucous membranes is common, and fever may occur early in the course of disease.

Immunocompromised children may develop progressive varicella, which is associated with prolonged viremia, visceral dissemination, and the development of pneumonia, encephalitis, hepatitis, and nephritis. Progressive varicella has an estimated mortality of ~ 20%. In thrombocytopenic patients, the lesions may be hemorrhagic. Adult patients with varicella are more ill and may develop pneumonia.

Reactivation of VZV is associated with the disease herpes zoster. Although zoster is seen in patients of all ages, it increases in frequency with advancing age, when cell-mediated immunity is waning. Clinically, pain in a sensory nerve distribution may herald the onset of the eruption, which occurs several days to a week or two later. The vesicular eruption is usually unilateral, involving one to three dermatomes. New lesions may appear over the first 5-7 days. Multiple attacks of VZV infection are uncommon; if recurrent attacks of a vesicular eruption occur in one area of the body, HSV infection should be considered.

Complications

The complications of VZV infection are varied and depend on age and host immune factors. Post-herpetic neuralgia is a common complication of herpes zoster in elderly adults. It involves persistence of severe pain in the dermatome after resolution of the skin lesions and appears to result from damage to the involved nerve root. Immunosuppressed patients may develop disseminated lesions with visceral infection, which resembles progressive varicella. Bacterial superinfection of varicella occurs and is usually caused by gram-positive cocci. Encephalitis may complicate varicella or zoster and may be associated with seizures and in some cases cerebellar signs.

Diagnosis

Varicella or herpes zoster lesions can usually be diagnosed clinically. Scrapings or swabs from the base of lesions may reveal characteristic cells with intranuclear inclusions or multinucleated giant cells identical to those produced by HSV. VZ virus can be isolated from aspirated vesicular fluid inoculated onto human diploid fibroblasts; however, the virus is difficult to grow from zoster (shingles) lesions older than 5 days, and cytopathic effects are usually not seen for 5-9 days. For rapid viral diagnosis, varicella zoster antigen may be demonstrated in cells from lesions by immunofluorescent antibody staining. PCR analysis of CSF may be useful to diagnose VZV encephalitis; cultures are rarely positive.

Treatment

Acyclovir (INN: Aciclovir) has been shown to reduce fever and skin lesions in patients with varicella (Box 33-5), and its use is recommended in healthy patients over 18 years of age if treatment is begun within 24-48 h of onset of rash. There is insufficient data to justify universal treatment of all healthy children and teenagers with antiviral agents. In immunosuppressed patients, controlled trials of acyclovir have shown efficacy in reducing dissemination, and its use is definitely indicated. In addition, controlled trials of acyclovir have demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment of herpes zoster in immunocompromised patients. Acyclovir (INN: Aciclovir) may be used to treat herpes zoster in immunocompetent adults, but it appears to have little or no impact on the development of post-herpetic neuralgia, the most important complication of zoster. Treatment should be started within 3 days of the onset of zoster. VZ virus is less susceptible than HSV to acyclovir, so the dosage for treatment is substantially higher. Famciclovir or valacyclovir are more convenient and may be more effective in preventing post-herpetic neuralgia. Some authorities recommend systemic corticosteroids for patients with zoster who are over 60 and have no contraindications. Although steroids do not prevent post-herpetic neuralgia, patients feel better and return to activity faster.

Prevention & Control

High-titer immune globulin administered within 72-96 h of exposure is useful in preventing infection or ameliorating disease in patients at risk for primary infection (ie, varicella) and serious complications (Box 6). Immunosuppressed children who are household or play contacts of patients with primary varicella are candidates for this immunoprophylaxis.

Once infection has occurred, high-titer immune globulin has not proved useful in ameliorating disease or preventing dissemination. Immune globulin is also not indicated for the treatment or prevention of reactivation (ie, zoster or shingles). In nonimmunosuppressed children, varicella is a relatively mild disease, and passive immunization is not indicated. Patients with varicella spread the virus by the respiratory route. In both syndromes virus is also present in the skin lesions. Varicella is a highly contagious disease, and rigid isolation precautions must be instituted in all hospitalized patients.

A live vaccine developed by a group of Japanese workers is effective and a single dose is now recommended for healthy children aged 12 months to 12 years and for selected healthy adults who are susceptible.

In immunocompromised children, chickenpox can be extremely serious, even fatal. For these children, the live vaccine is being evaluated and is not currently recommended.